Business schools identify the sources of competitive advantage that tie customers to companies and what they produce. Fundamentally though, there is only one true competitive advantage: people.

If I could recommend one book for long-term investors, it would be “Intelligent Fanatics Project” by Sean Iddings and Ian Cassell, which is subtitled “How great leaders build sustainable businesses”.

The book analyses what the chief executives who ran some of the world’s most successful businesses did, in the expectation of finding common factors that would enable the authors to identify and invest in great businesses early on in their stories.

They stop short of identifying great businesses of the future, but give plenty of pointers to help us find them. One is incentives, discussed in an earlier article on businesses where the executives have skin in the game. But the authors conclude that there is only one true sustainable competitive advantage:

“What the intelligent fanatic model proposes is that the only truly sustainable competitive advantage is a company’s human capital. Eventually, competitors can and will copy products, but it is extremely hard to copy a strong culture.”

Now you might think this is a somewhat nebulous concept, and one that would be particularly hard to use as the inspiration for filtering a vast financial database like SharePad but I’m going to give it a go.

Anatomy of a winning culture

First let’s tease out a bit more about what makes a strong culture. The authors say deeply rooted corporate cultures are built over years, “one hire at a time”, citing Herb Kelleher of Southwest Airlines.

Keheller was the cofounder of Southwest in 1967 (it didn’t fly until 1971) and he remained involved in the business until he died earlier this year. Southwest grew from a tiny Texan airline with three planes to be the world’s most profitable, pioneering a low-cost business model that spawned many imitators. Its long-term success though, came down to putting people first:

“One of the things that we do is continue to emphasize that we value our people as people, not just workers. Any event that you have in your life that is celebratory in nature or brings grief, you hear from Southwest Airlines. If you lose a relative, you hear from us. If you’re out sick with a serious illness, you hear from us, and I mean by telephone, by letter, by remembrances from us. If you have a baby, you hear from us. What we’re trying to say to our people is, “Hey, wait a second, we value you as a total person, not just between eight and five.””

By treating its people well, Southwest was showing employees how it wanted them to treat colleagues and customers. Iddings and Cassell say:

“Customers are happier, employees are happier, and if you make those two groups happy, then shareholders are happier.”

Founders retire, patents expire, and brands sometimes falter, but a company will adapt and prosper if it has good people, which is why, the authors claim, the most successful organisations over the long-term set themselves up as perpetual recruitment machines, “attracting, training, and retaining the best human capital”.

Kelleher remained connected with Southwest until he died earlier this year, although he stepped down as chief executive in 2001 and chairman in 2008. The company has had two chief executives since, both of them internal promotions.

Perpetual recruitment machines

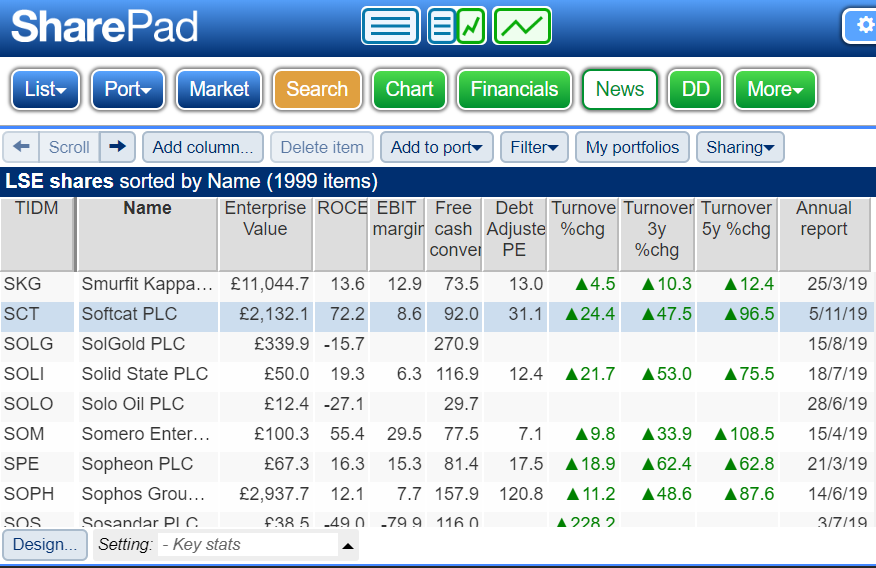

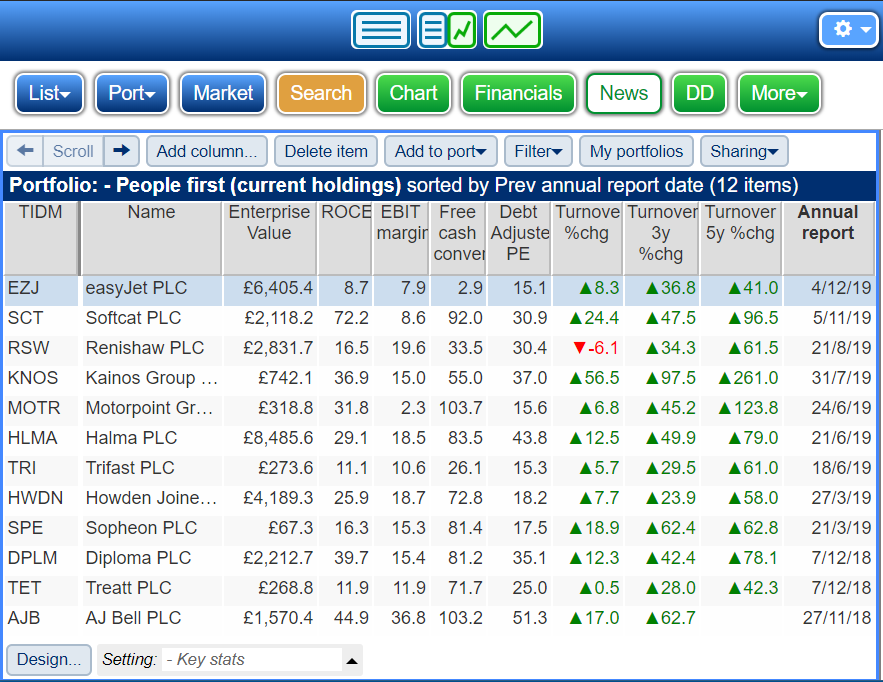

The idea of perpetual recruitment machines brings to mind the outlandishly successful computer hardware and software reseller Softcat. SharePad will tell you Softcat is a tremendous business. Here is a snapshot:

Yet much like Southwest, the industry Softcat has flourished in is not known for high levels of profitability.

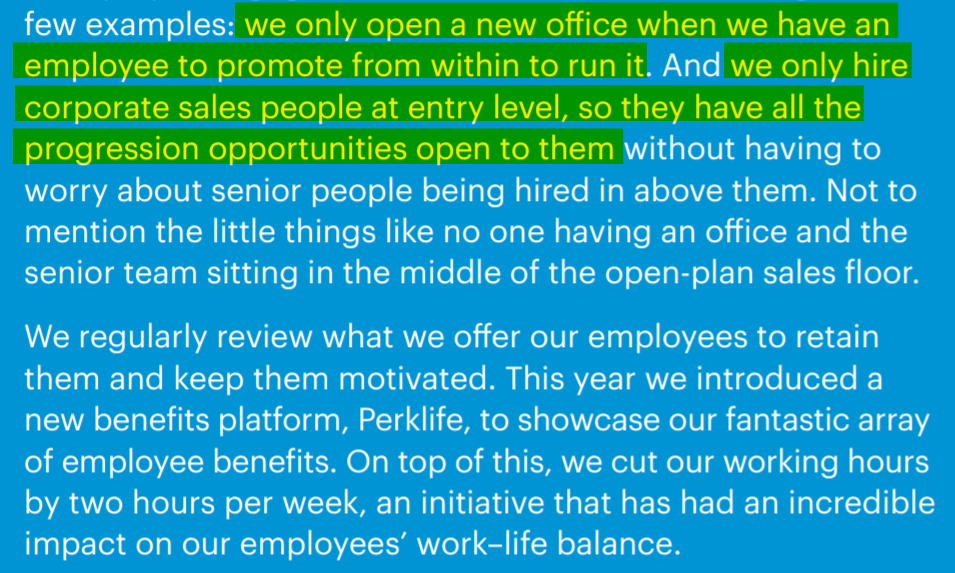

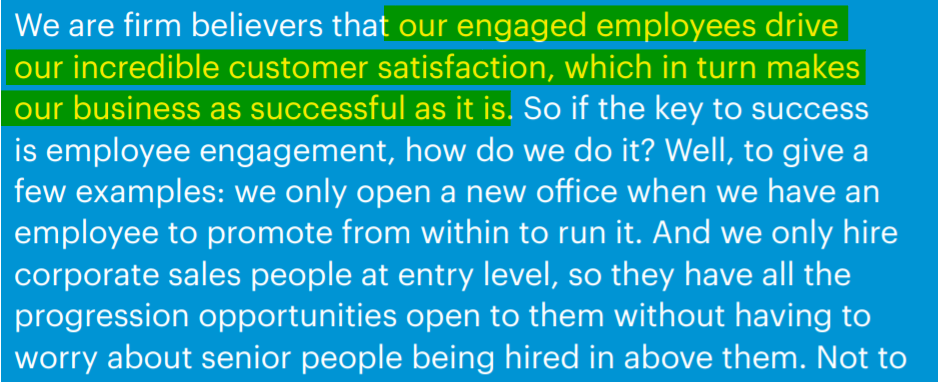

Here are a few words from Softcat’s recent annual report, before we go off in search of more businesses like it. Basically, it is a perpetual recruitment machine attracting, training and retaining the best people because it does not make senior hires, it recruits junior sales people, trains them, and promotes them:

So how do we find these paragons of people power?

The answer may be earlier in the same paragraph, in which Softcat explains:

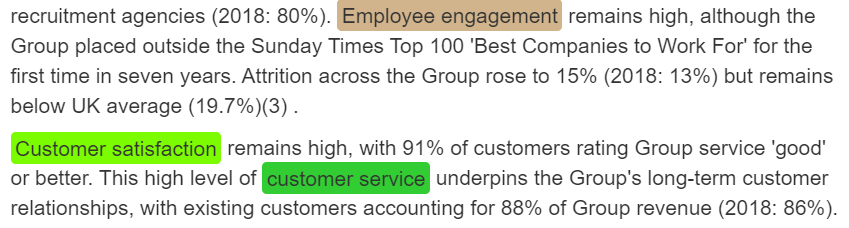

Companies use jargon to describe and measure how they treat people, words like “employee engagement” and “customer satisfaction”. Since it is not compulsory to measure these things, or boast about them, it stands to reason that those firms that use these measures as “key performance indicators” may well be creating or cementing winning corporate cultures.

Filtering for people first businesses

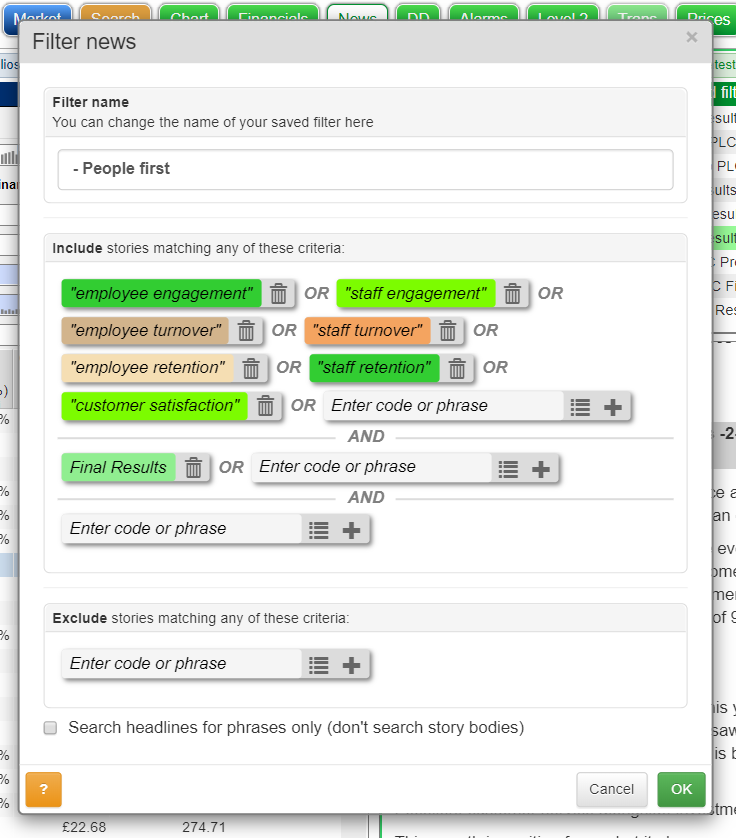

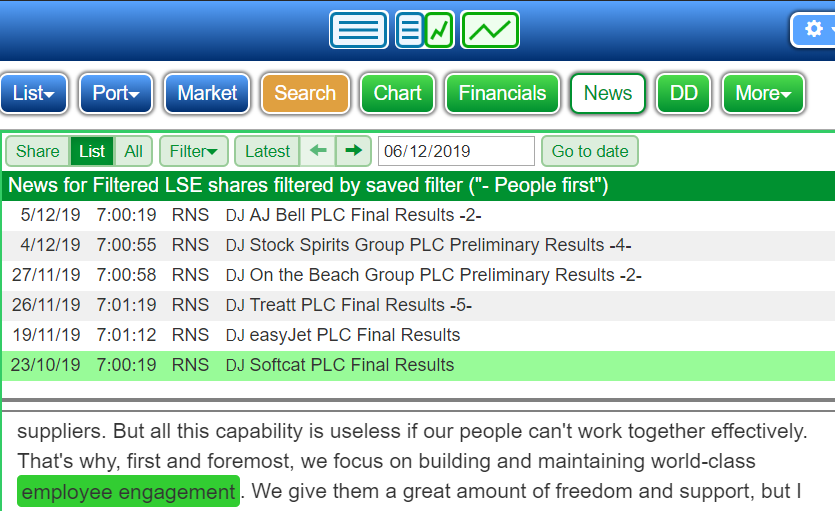

Here is my first human capital engagement news filter, otherwise known as “People first” 🙂

It searches final results statements for keywords that indicate a company may be a recruitment machine.

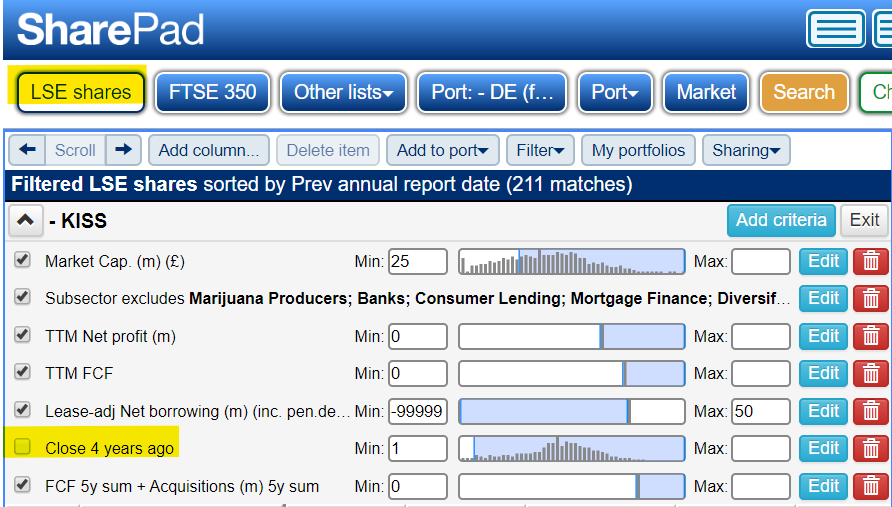

To achieve a manageable shortlist, I applied the People first news filter to a list of 211 shares returned by another filter, my Keep it Simple filter, which discards companies because they’re unprofitable, heavily indebted, or have radically changed through acquisition:

I switched off the criterion that requires a company to have been listed for four years to snag youthful people first businesses like AJ Bell. The investment platform floated last year, but its latest results described a number of people-first initiatives including an eye-catching donation of £10m share options to charity, as long as certain performance criteria are met. No doubt it will motivate employees and customers as well as differentiate the company from some of its competitors.

You can see Softcat in the list as well:

And Treatt, a company very close to my heart, is there too. It supplies flavours and fragrances to wholesalers and direct to large multinational companies like soft drink manufacturers. Four years ago, I shadowed the chief executive, Daemonn Reeve for a morning. The assignment took me to a talk he gave to the Suffolk Chambers of Commerce on, you guessed it, “employee engagement”. Echoing the chief executives in Intelligent Fanatics Project, he said of employee engagement:

“It’s not going to cost you money. It’s going to make you money.”

And…

“If you concentrate on the numbers in the business, nothing changes. Concentrate on the staff and everything changes.”

Treatt is transforming itself from being a bulk supplier of citrus oils to a developer of specialist flavours designed in laboratories with customers to recreate particular tastes and smells and mitigate the nasty taste of healthy alternatives to sugar. The transformation is impacting every facet of the business, and as it changes Trate must carry its people with it. Comfort comes not only from the words of the company, but from the staff itself (on the whole). Take a look at the reviews on recruitment site Glassdoor, 91% of reviewers would recommend the firm to a friend and 94% approve of the chief executive.

Fifty-nine of the 211 companies have mentioned employee engagement jargon in their most recent annual reports (i.e. during the last year), which is still too many for a shortlist. Many of them only mention them in passing, though. Stock Spirits mentions an employee engagement survey and says “the [undisclosed] results are being acted upon”, which doesn’t get us very far.

SharePad’s colour coding enables us to scroll down the documents to read the context. This is more promising, from Kainos (recently profiled by SharePad columnist Alistair Blair), because it includes numbers. In fact kudos to the company for reporting figures that have deteriorated slightly:

People first portfolio

Having been through the list, I’m pleased with the companies I have found…

…But disappointed there aren’t more firms talking seriously about their people focused cultures and fear I have excluded some companies because they are not expansive on the subject when they are people focused businesses under the hood. From my experience, I have added Howden Joinery, Trifast, Motorpoint, and Diploma to the list even though they didn’t use the jargon of employee engagement in their results. Perhaps I need to experiment with new keywords, or perhaps I need to turn to another kind of document.

Final results statements are rarely text-only versions of annual reports. They are, primarily, concerned with financial performance. In their eagerness to give the market this information quickly, companies often defer some of what we might term “the soft stuff” to the annual report, which is usually published later.

Richard Beddard.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.