Richard analyses Bloomsbury Publishing’s segmental report to work out where the profit is coming from. The Harry Potter effect is still evident, but the company is conjuring up another source of profit without recourse to magic.

My last article ended on something of a cliffhanger because I had found something out, but I did not know what to make of it.

More than a decade after peak Harry Potter, the wizarding books are still Bloomsbury Publishing’s biggest money spinner, judging by the fact that five of the publisher’s ten best sellers are from the Harry Potter stable and “Children’s Trade”, the division that includes Harry Potter, is by far Bloomsbury’s biggest.

So how big is this dependency? And is it a good thing or a bad thing?

Delving into the segmental report

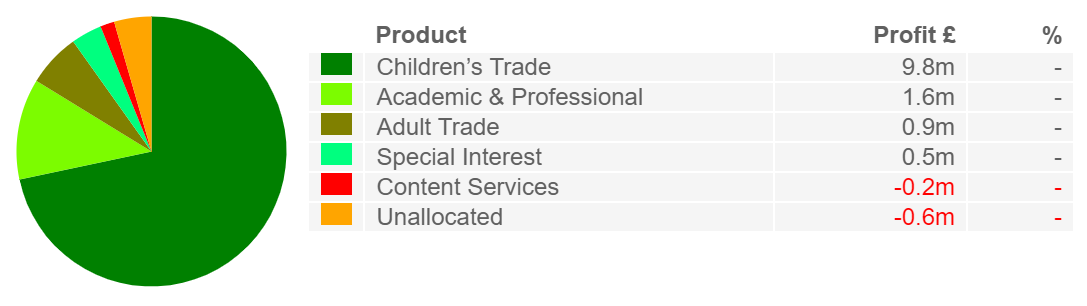

To get a quick impression, we can use SharePad. Under financials > company we can see a pie chart showing how much revenue and profit Bloomsbury earned from each of its divisions in the financial year to June 2019. The Children’s Trade division earned 40.5% of revenue…

The Children’s Trade division earned a significantly bigger chunk of profit. SharePad does not calculate the percentage because one very small division, “Content Services”, which provides content for company websites and marketing, made a loss:

But we can easily work out the contribution of the Children’s Trade division to the total profit of the four profitable divisions: Children’s Trade, Academic & Professional, Adult Trade, and Special Interest. It is a whopping 77%.

We can also easily work out the profit margins of each division, since the profit margin is simply profit as a proportion of revenue. Here they are:

| Division | Profit/Revenue | Profit margin |

| Children’s Trade | 9.8/65.8 | 15% |

| Academic & Professional | 1.6/41.2 | 4% |

| Adult Trade | 0.9/33.5 | 3% |

| Special Interest | 0.5/21.2 | 2% |

The Children’s Trade division looks like a highly profitable business. For every pound of revenue it earns 15p of profit. The others look like duds! For every pound of Academic & Professional Revenue Bloomsbury earns 4p.

Taking out the sunk costs

But there is a wrinkle we need to iron out: acquired intangible assets. Bloomsbury has been diversifying, building up the other divisions so it is not as dependent on Children’s Trade by buying other businesses.

The acquired intangible assets are sunk costs, values assigned by accountants to brands, customers and so on at the time the company bought them. Bloomsbury must amortise, or write down, the value of these assets over time as if they were being worn out, just like machinery is depreciated. If Bloomsbury acquires an imprint (publishing brand), for example, it must reduce its value every year, a cost that is also deducted from profit. At the same time it may well be spending money to promote the imprint and make it more valuable. In a sense, the accounting means the company is charging itself twice, once for the historical cost of developing the imprint and once for its continuing development. This would not be the case had the company developed it from scratch so to judge the ongoing profitability of each business unit we need to add back amortisation of acquired intangible assets to put the divisions that have made acquisitions on the same footing as the Children’s Trade division, which has not.

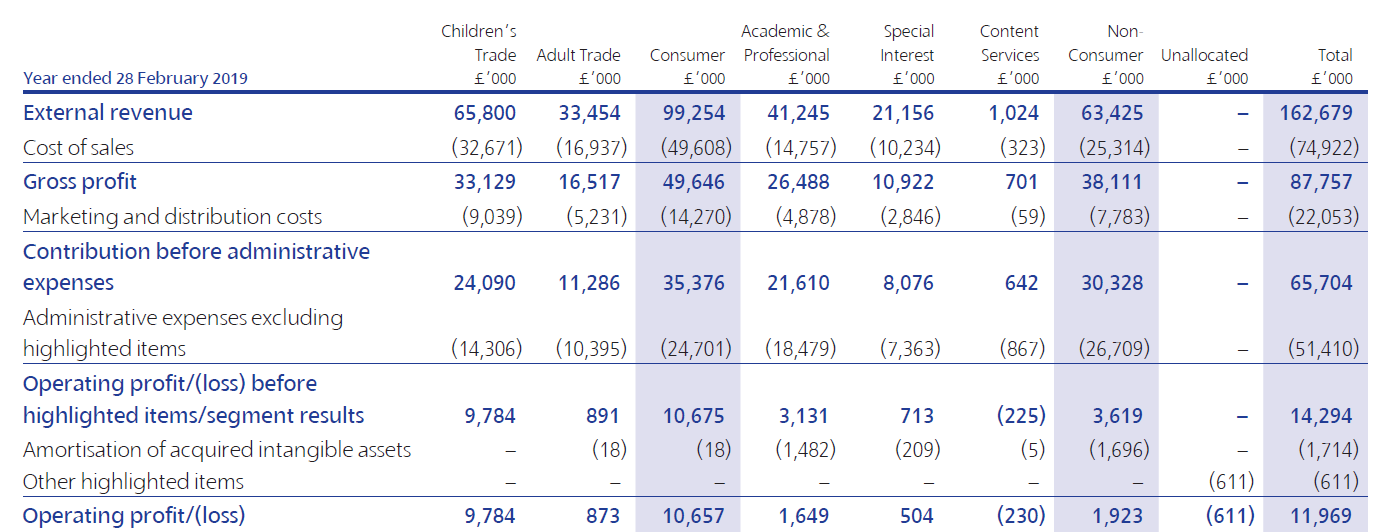

To do that, we need to find the company’s segmental analysis, from which SharePad derives its data, and dig into the details. It is in Note 3, on Page 101 of the 2019 annual report. Helpfully, Bloomsbury breaks out acquired intangible assets:

The line we are interested in is profit/(loss) before highlighted items/segment results. That is before amortisation of acquired intangible assets (there are no other highlighted items) is deducted from profit. Bloomsbury publishes its results in units of thousands, as opposed to millions like SharePad, which is why the table below looks so different from the one above. As you can see the profit margin for Children’s Trade is the same, but there is an improvement in the divisions that made acquisitions:

| Division | Profit (ex. Amortisation of acquired intangibles)/Revenue | Profit margin |

| Children’s Trade | 9,7848/65,800 | 15% |

| Academic & Professional | 3,131/41,245 | 8% |

| Adult Trade | 891/33,454 | 3% |

| Special Interest | 713/21,156 | 3% |

But I am still confused. One of Bloomsbury’s objectives is to diversify into non-consumer (i.e. Academic & Professional, Special Interest and Content Services, which it says are “higher margin” and “more predictable”. Subscriptions to databases and textbooks required by students are more predictable income streams than fiction, it is not often you strike gold with an author like JK Rowling, but higher margin than what? Margins in Academic & Professional are half those in Children’s Trade.

Perhaps publishing so many copies of the same Harry Potter books makes the Children’s Trade division so profitable, but the rest of the business, even other Children’s fiction, is more pedestrian, an observation that looks true if we extend the analysis back a few years:

| Division / Profit margin | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 |

| Children’s trade | 15% | 17% | 18% | 14% |

| Adult trade | 3% | -1% | -2% | 2% |

| Academic & Professional | 8% | -1% | 5% | 11% |

| Special Interest | 3% | 10% | 4% | 11% |

I do not think things are as bad as they look, but before I explain why let me sum up what I have learned about Bloomsbury’s strategy as I dotted around the accounts.

Matching the numbers to the strategy

Bloomsbury owns the rights to a proven money spinner, and as parents pass on their childhood enthusiasm for Harry Potter, interest endures and may even grow. That was founder and chief executive Nigel Newton’s view, published in an interview in the Guardian last year.

But Bloomsbury does not like the economics of the industry that gave it this huge asset, it is too dependent on blockbusters and retail booksellers (which are dominated of course by He Who Must Not Be Named (no, not Voldemort, Amazon).

It is seeking to balance the risky world of publishing fiction with more dependable non-consumer products by investing heavily, particularly in its second biggest division (currently 25% of turnover). That market has established competitors and Bloomsbury’s academic and professional titles and databases have yet to earn it particularly high profits.

The missing piece in the jigsaw may be the high cost of developing new digital subscription products for academic libraries, which is weighing on profit. Bloomsbury announced this digital investment programme in 2016, and since then we can see in the table above that profit margins in Academic & Professional have slumped from 11%, and partially recovered to 8%. Maybe the company is starting to see a return from its investment, and profits in this division will increase further in future. That is Bloomsbury’s expectation

Revenue in the Academic & Publishing division increased 42% in 2019. I must admit, I am intrigued. Harry’s days of dominance could be numbered, and for the best of reasons – because the Bloomsbury is engineering another enduring source of profit.

No magic necessary.

Richard Beddard.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.