“It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.” – Warren Buffett

“The desirability of a business with outstanding economic characteristics can be ruined by the price you pay for it. The opposite is not true.” – Charlie Munger

The quote from Warren Buffett above is often cited to explain his investment strategy. Buffett has long since moved away from buying cheap unloved companies and now focuses his attention on investing in high-quality companies.

He knows that outstanding businesses are rarely available at cheap prices and therefore emphasises his willingness to pay a fair price for them. But what does he mean by fair?

As his long-term business partner Charlie Munger has pointed out, if you pay too much for a high quality business you can end up with a lousy investment. So how are investors to find the right trade-off between quality and price?

Recent years have seen a significant rise in the share prices of quality companies. This has underpinned the excellent returns of well known fund managers like Terry Smith and Nick Train. Both invest in a concentrated portfolio (less than 30 shares) of high-quality companies and hold them for a long time. In many ways they have joined Buffett as successful practitioners of long-term buy and hold quality investing.

I am a big fan of quality investing and follow this approach in my ISA and SIPP portfolios. However, I do not believe that high-quality companies are a buy at any price, even with a long-term investing mindset.

In this article, I am going to look at the trade-off between quality and price and try and work out how much an investor should pay for shares in a quality business.

What does a quality company look like?

I define a quality company as one having the following four characteristics:

- A high and stable return on capital employed (ROCE).

- A high proportion of profits that turn into free cash flow.

- Strong finances – a high fixed charge cover and no big pension fund deficit.

- Capable of growing profits and cash flows in the future.

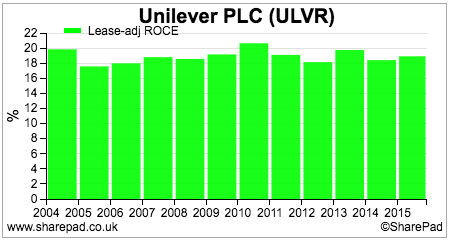

Companies with these characteristics are well suited to long-term buy and hold investing. A long holding period allows the high ROCE to compound (think of it like rolling a snowball in the snow) to create a more valuable business. A company such as Unilever would be a good example of this.

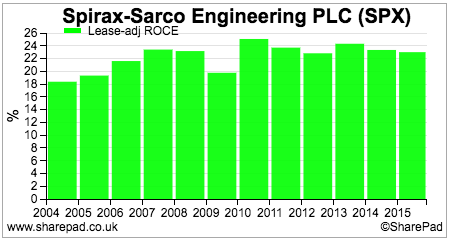

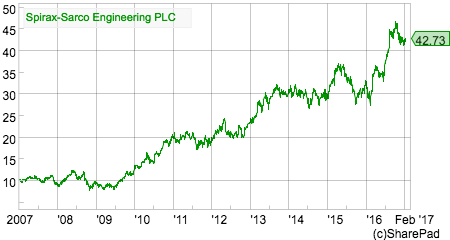

Spirax-Sarco would be another.

Shares in both these companies have proven to be more than respectable long term investments, but is just focusing on quality all an investor needs to do?

Does price matter?

I think it definitely does. A detailed study by US investment company MFS in 2015 shows that buying quality companies regardless of their price is not a good strategy. Get the right mix between quality and price though and the results can be very good indeed.

MFS looked at the performance of the largest 1000 US shares by market capitalisation between 1974 and 2014. It split the shares into three groups:

- High quality (High return on equity, stable profits, low debts)

- Cheap (low PE)

- A mixture of high quality and cheapness.

It then looked at how these groups had fared against the stock market as a whole and calculated their excess return (how much they had beaten the market by).

| Type of share | Average annual excess return |

Cumulative excess return 1975-2014 |

|---|---|---|

| High quality | 0.05% | 1.80% |

| Cheap | 4.43% | 357% |

| Quality + Cheap | 4.99% | 452% |

| Source: MFS | ||

Just buying quality shares did no better than the stock market as a whole. Buying cheap did well, but buying quality and cheapness did even better. These results also held for non-US stock markets as well.

This is not a new finding in the world of investing. Joel Greenblatt’s Magic Formula approach adopts the same strategy of matching quality with cheapness and has produced pretty good results. However, as I found in my 2016 study of Greenblatt’s strategy just buying very cheap shares produced very good results. When mixed with quality they did better.

One of the most interesting conclusions from the MFS study was that the quality of companies was long-lasting. This is probably due to something known as a “moat” – the company has something like a brand or technology that competitors cannot copy. Good companies stay good. Lower-quality companies didn’t tend to get better.

I am happy to accept that the price you pay does matter when it comes to quality investing.

How much to pay for a high quality business?

My approach is to use the Buffett measure of valuing business.

Share value = Cash profits per share/Yield on long-term government bonds

However, if you are looking at quality companies which are turning most of their profits into free cash flow you can use earnings per share (EPS) as a proxy for cash profits.

Under Buffett’s formula you would divide EPS by the yield on 10 year UK government bonds which at the time of writing is 1.44%. This in my opinion would be a mistake.

The reason I say this is that using such a low rate would imply a very high valuation for a share. Dividing EPS by a yield is the opposite approach to applying a multiple to it. To get the multiple just do the following:

Implied Multiple = 1/Yield

So a yield of 1.44% gives an implied PE multiple of 69.4 times. How many shares are really worth that?

Not many in my view. The reason for this is that bond yields are too low – I am saying that bonds are overvalued. If you are going to use this Buffett method you are going to have to adjust for this overvaluation.

For much of the last 30 years UK 10 year government bonds have yielded roughly 3% more than inflation (measured by the retail prices index or RPI). With the RPI currently 2.2% this would suggest a fair value 10 year bond yield of 5.2% (2.2% inflation plus 3%). This would give a fair PE of:

Fair PE = 1/0.052 = 19.2 times.

Let’s keep things simple and say up to 20 times earnings (a PE of 20) is a fair PE to pay for shares of a high-quality company. That’s still quite high in many people’s eyes. How can anyone justify paying this much?

Here’s some thoughts as to why:

- Companies with stable and predictable profits and cash flows are less risky than lots of others out there. This has often seen them referred to as “bond-like” or “bond proxies”.

- High-quality companies with high ROCE and strong free cash flows are scarce and therefore have scarcity value.

- Over the long run, the continued steady growth and stability of profits and cash flows will make the business more valuable for long-term investors.

Are many quality company shares too expensive?

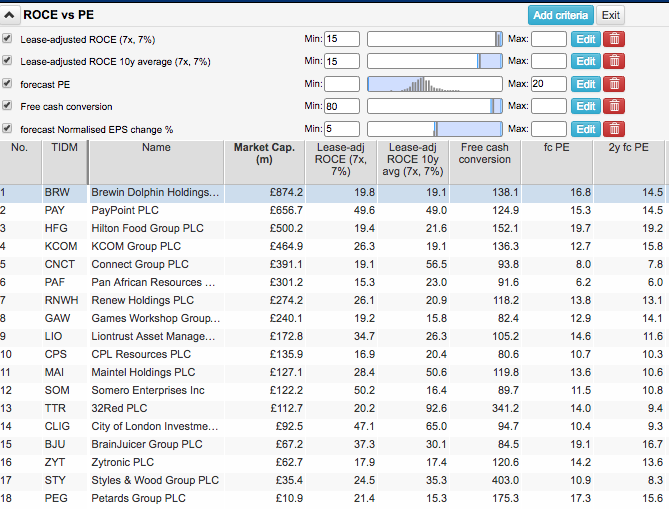

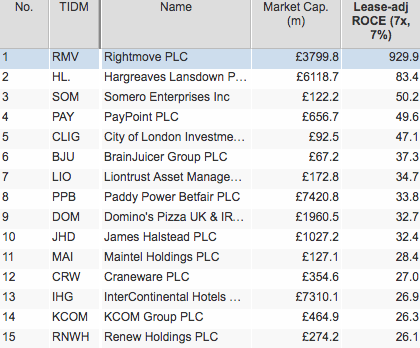

Above is a list of shares that meet the following quality criteria:

- Minimum current and 10 year average lease-adjusted ROCE of at least 15%.

- Current free cash flow conversion (EPS into FCFps) of at least 80%.

- Forecast EPS growth of at least 5%.

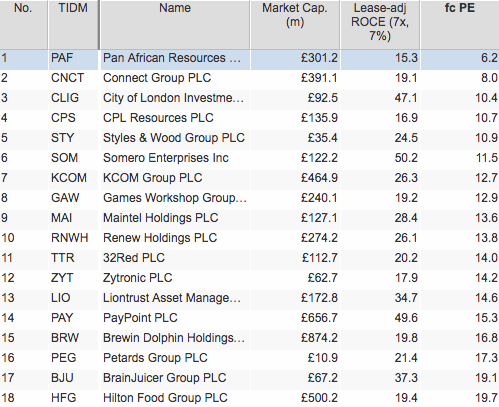

This provides a list of 40 shares, many of which are outstanding businesses. Now see what happens when we impose a maximum valuation of 20 times PE.

Not only do over half the original shares on the list disappear, but you will also notice that companies with big market capitalisations do as well.

Are big cap quality shares therefore overvalued? I know of commentators who take this view and can see why they do. Or should the long-term investor (more than 10 years) take the plunge and buy anyway?

There is an argument – held by people such as Terry Smith – that as long as the valuation is not too extreme then the steady growth over the long haul that these companies might be expected to produce will pay off.

Another alternative it to keep hold of your cash and start looking for tomorrow’s great businesses before they become great. I’ll leave that subject for another time.

2017 Test portfolios

In order to monitor this fascinating ongoing debate, I am going to set up a couple of test portfolios to keep track of in the year ahead. Both will contain 15 shares which meet my quality criteria. The first portfolio will contain the companies with the highest current ROCE. The second one will contain the quality shares with the lowest PEs (below 20).

Quality only

Quality and price

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.