Buying a share at a discount to its book (or net asset) value ought to be the safest way of investing.

Indeed, what could go wrong if you can effectively buy assets worth £1 per share for, say, 50p?

The reality — sadly — is not always that simple.

Let me show you what I mean by using SharePad to find a price-to-book ‘bargain’.

Filter criteria

Similar to everything else with the stock market, screening for ‘asset plays’ involves certain nuances.

For a start, you should focus on tangible rather than intangible assets. Tangible assets physically exist and are therefore more likely to have a real-life cash value.

Furthermore, a price-to-book ‘bargain’ ought to have a record of success to underpin the value of the assets in question. Most companies that sport market caps below their asset value are in fact total basketcases that have lost money for years.

For this SharePad screen, I have therefore sought companies that offer respectable dividend histories as well as bumper asset positions.

The exact filter criteria I employed were:

1) A price to net tangible asset ratio of between zero and one;

2) A minimum dividend payment history of ten years, and;

3) A forecast dividend yield of zero or more.

(You can run this screen for yourself by selecting the “Maynard Paton 28/08/19: Hammerson” filter within SharePad’s ace Filter Library. My instructions show you how.)

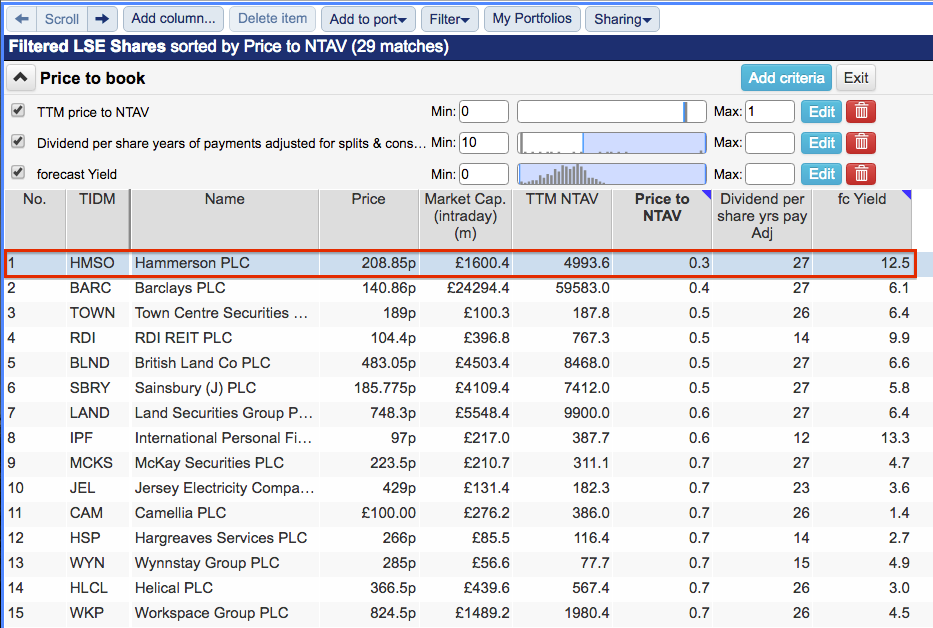

SharePad returned 29 shares — most of which were property companies.

I chose Hammerson — a FTSE 250 real estate investment trust — simply because its price to book of 0.3 was the lowest on the list.

The filter results showed Hammerson’s net tangible assets of £5 billion could be acquired for a £1.6 billion market cap.

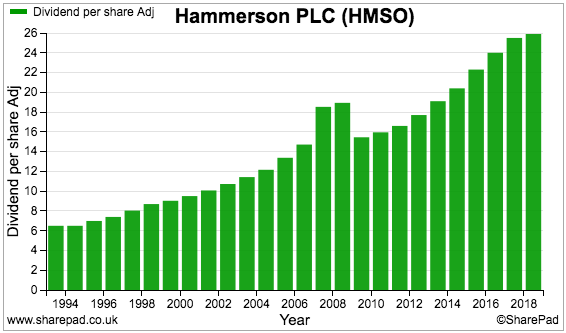

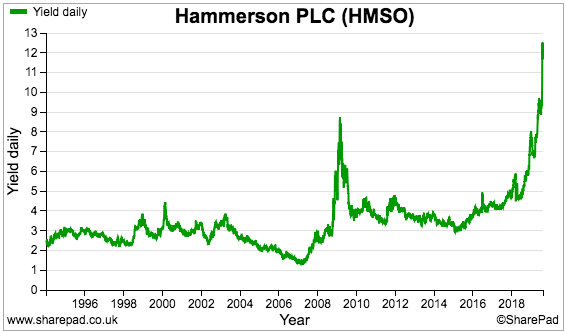

SharePad also revealed an impressive 27-year dividend run, which suggested the firm was not a basketcase, and a 12.5% forecast yield, which admittedly seemed far too good to be true.

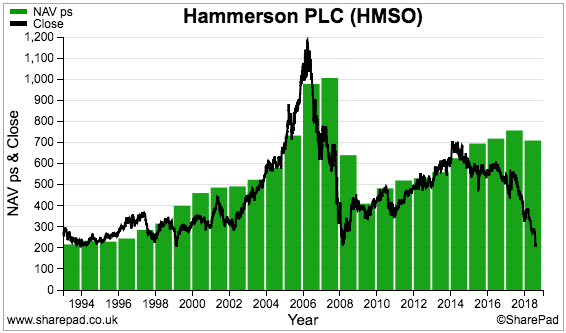

Let’s first compare Hammerson’s share price to its net asset value (NAV) per share:

The share price broadly followed NAV up and down until 2016, at which point the share price dropped towards 200p while NAV per share was maintained at approximately 700p.

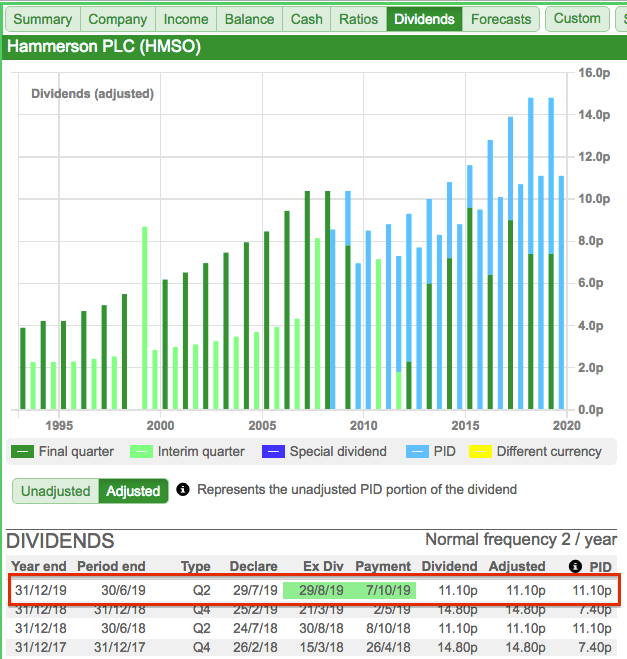

SharePad confirms the reliable dividend history:

And the dividend yield has indeed reached 12.5%:

Double-checking SharePad’s Dividends tab reveals Hammerson — just a few weeks ago! — maintained its first-half payout at 11.1p per share:

I can only presume Hammerson reckons its dividend can be sustained, and so the aforementioned 12.5% yield might actually be genuine.

The history of Hammerson

Hammerson was established during 1942 when Lewis Hammerson sold his family clothing business to embark on a property career.

Initially developing residential property, Mr Hammerson ventured into commercial property through the purchase of a London office block in 1948.

During the 1950s, the business began to develop shopping districts and an early success was the redevelopment of Bradford city centre.

The group completed the country’s first ‘out-of-town’, indoor shopping centre — the Brent Cross development in London — during 1976.

These days Hammerson owns — or co-owns — 21 major shopping centres, 12 retail parks and 20 designer outlets throughout the UK and Europe.

Notable assets include the Bullring in Birmingham, Cabot Circus in Bristol, Silverburn in Glasgow and the Bicester Village outlet centre. Less prominent sites include the Cleveland retail park in Middlesborough, the Central retail park in Falkirk and the Cyfarthfa retail park in Merthyr Tydfil.

Major tenants include H&M, B&Q, Next, Marks & Spencer and Boots.

Hammerson is a pure retail-property landlord — the group decided in 2012 to sell its office blocks “in order to generate superior, sustainable returns for shareholders” through shopping centres. That strategic change has exacerbated the firm’s current predicament.

Hammerson’s accounts are not straightforward because the group does not own many of its flagship sites outright. Brent Cross, the Bullring, Cabot Circus and other popular centres are actually 50% (or more) owned by other parties.

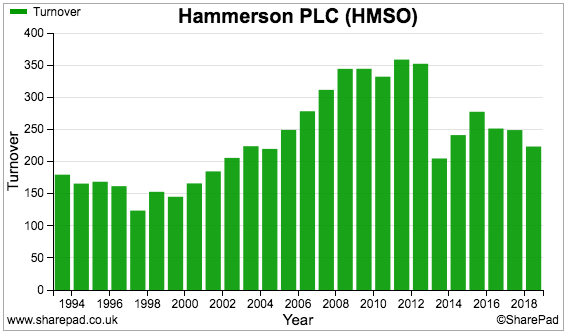

The ownership structure has complicated Hammerson’s revenue. Before 2013, reported revenue included Hammerson’s share of its part-owned centres.

But new accounting rules have since meant reported revenue reflects only income from the majority-owned sites.

The chart below shows Hammerson’s reported revenue:

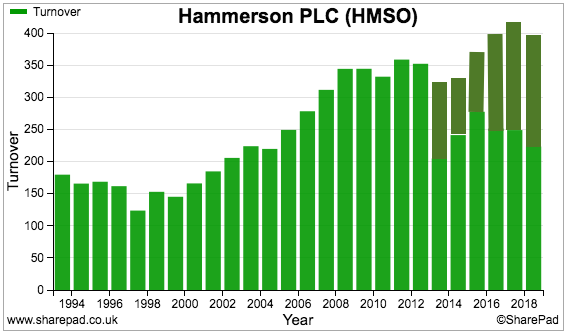

And this chart — with the dark-green bars added by me — shows revenue on a consistent basis that includes Hammerson’s income from shopping centres not under the group’s full control:

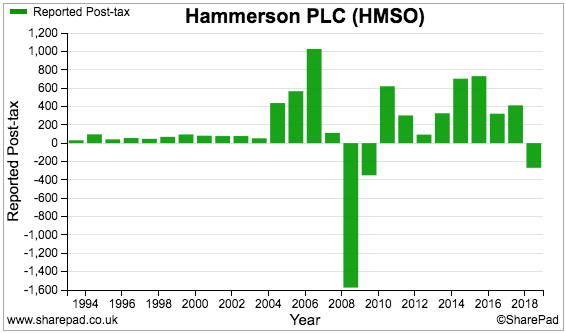

My chart-editing skills are unfortunately not good enough to re-jig Hammerson’s profit history.

Not only were the reported profit figures affected by that new accounting rule, but valuation changes — most notably during 2008 — and all sorts of other losses and costs have made the group’s underlying figures rather academic.

I will therefore leave you with Hammerson’s unadjusted earnings:

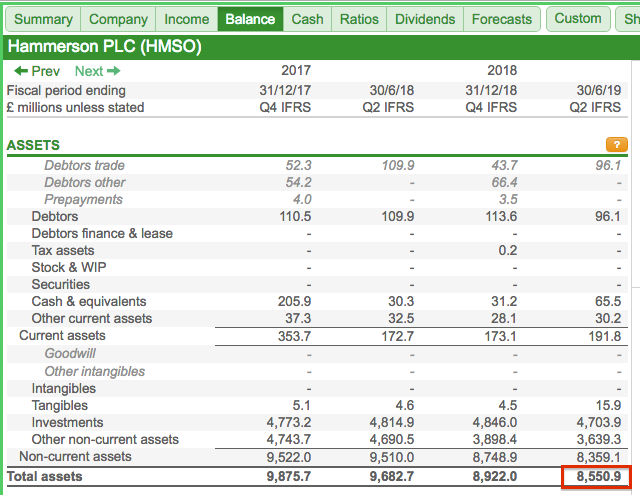

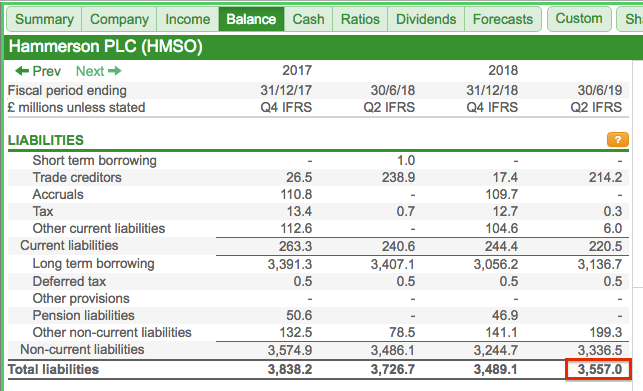

Balance sheet

Let’s turn our attention to the all-important balance sheet.

SharePad shows the group carried assets of £8.6 billion at the June half year:

Those assets were offset by liabilities of £3.6 billion (of which almost all were represented by debt):

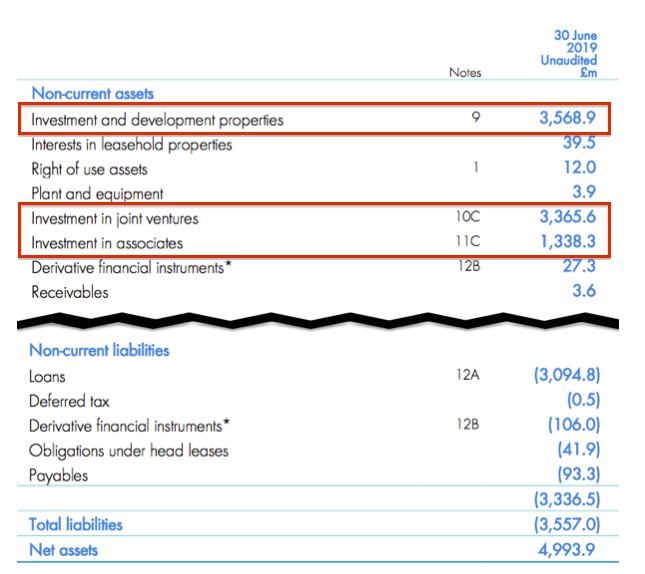

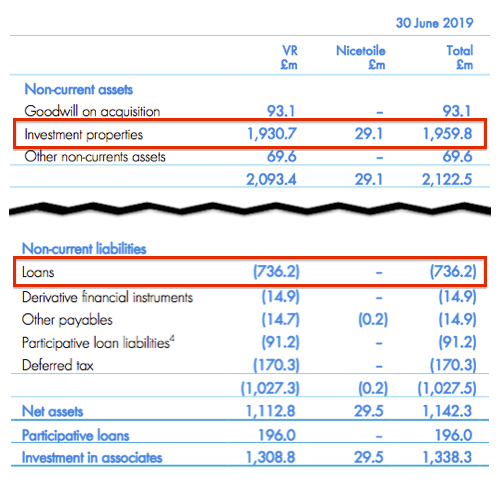

To justify any price-to-book investment, the underlying assets have to be identified. July’s interim results showed this balance sheet:

Hammerson boasted directly owned properties with a £3.6 billion book value plus investments in joint ventures and associates with a £4.7 billion book value.

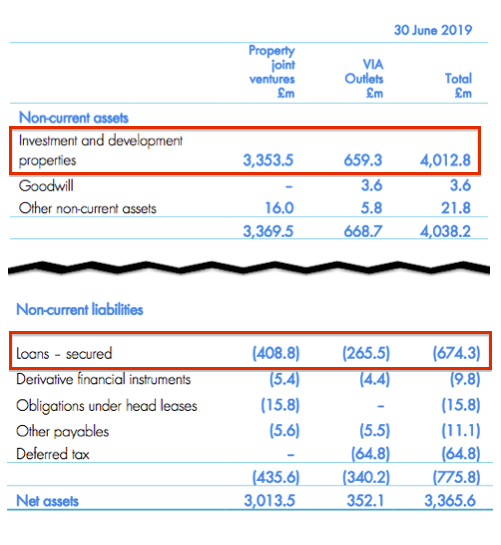

The interim results revealed the joint-venture investment was represented mostly by property with a £4 billion book value and debt of almost £700 million…

…while the associates investment was represented mostly by property with a £2 billion book value and debt of more than £700 million:

All told, Hammerson’s property stands at £9.6 billion and debt stands at £4.5 billion.

The obvious question then — why is Hammerson’s market cap only £1.6 billion given the net book value of the group’s shopping centres and debt is £5 billion?

The answers lay in the same interim results.

Interim results

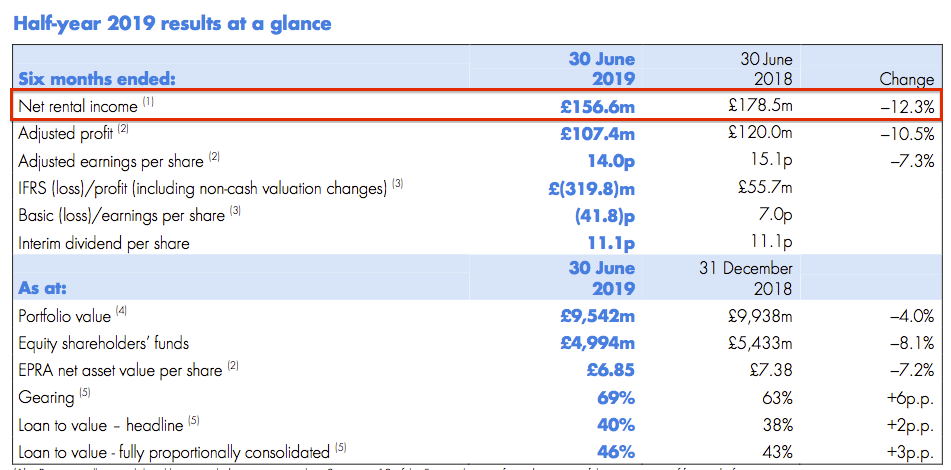

Hammerson’s figures for the first half of 2019 were dire:

By far the most shocking headline statistic was net rental income diving 12%.

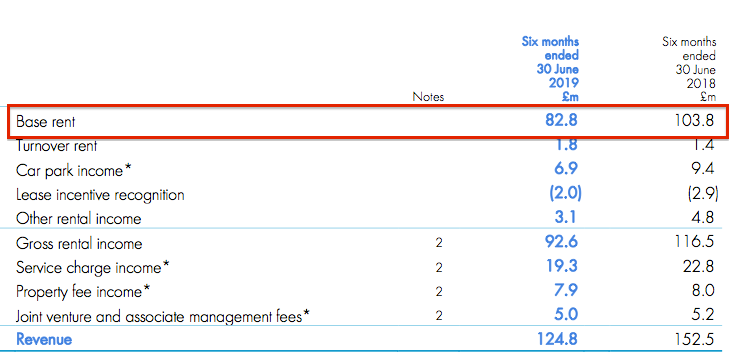

Dig a little deeper into the statement, and base rents at the directly owned sites plunged 20%:

Hammerson blamed the shortfall on the “undoubtedly challenging” conditions within the retail sector.

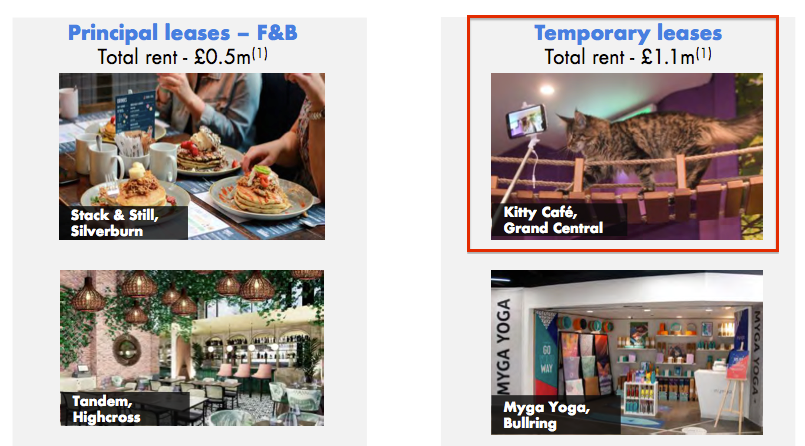

Underlining the difficulties, the company admitted “principal lease” renewals at its flagship sites had dropped by 8%.

In addition, temporary leases — which run for up to three years — currently generate income 26% below their previous levels.

Perhaps the clearest evidence of trouble was news that a cat-themed restaurant opening its third site was described as a “key” deal:

“Key leasing deals during 2019 included:

At Grand Central [Birmingham]… Kitty Café, an F&B operator where customers can interact with 30 rescue cats, replaced Handmade Burger which closed following its administration.”

The overall rental performance was a far cry from earlier years, when net rental income used to advance by a regular 2% or so per annum.

The chief executive admitted the balance sheet must now be shored up (my emphasis):

“Our absolute priority remains to reduce debt. We stated our intention to achieve over £500m of disposals in 2019 and even in this tough environment where deals are taking longer to transact, we are now most of the way there. We will continue to pursue additional sales throughout 2019 and into 2020 to further strengthen our balance sheet.”

And notable disposals have already started (my emphasis):

“We have exchanged contracts for the sale of 75% of Italie Deux, Paris for €473 million (£423 million), reflecting a net initial yield of 4.1% and a 8.5% discount to December 2018 book value.”

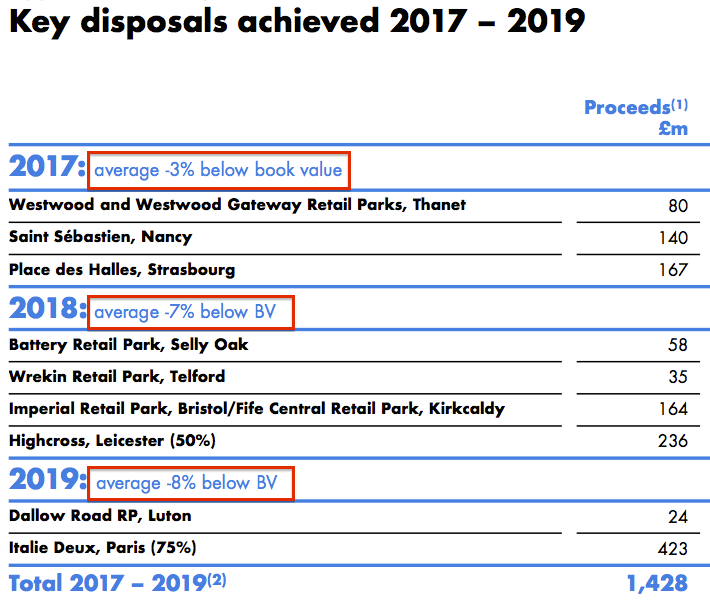

Oh dear — Hammerson is selling properties at a chunky 8.5% below their stated book value. The results presentation revealed the discount had widened during recent years:

Cash flow, interest payments and dividends

Hammerson’s cash flow spotlights the precarious financing of the group’s directly owned centres and why properties must now be sold.

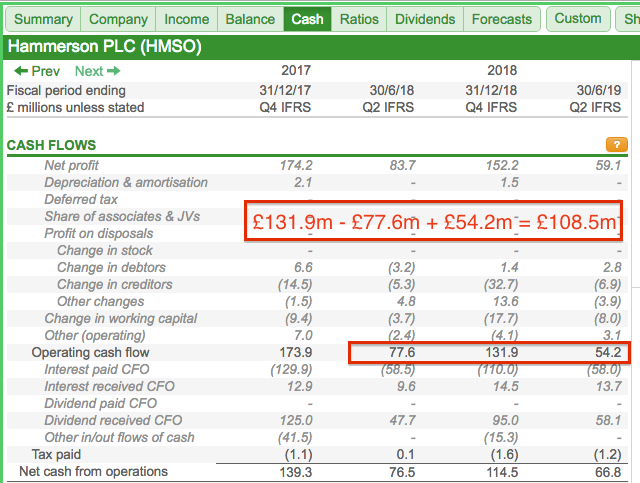

We can work out from SharePad that the second-half of 2018 plus the first half of 2019 produced aggregate operating cash flow of £109m:

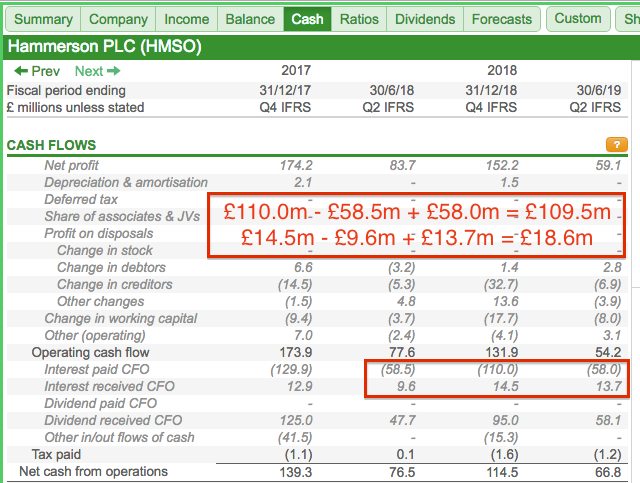

We can also work out that, during the same twelve months, interest paid was £110m and interest received was £19m to give net interest paid of £91m:

Operating cash flow of £109m less net interest paid of £91m leaves only £18m to spare.

Further rental difficulties could therefore leave the directly owned properties not generating enough cash to pay the interest on the group’s borrowings.

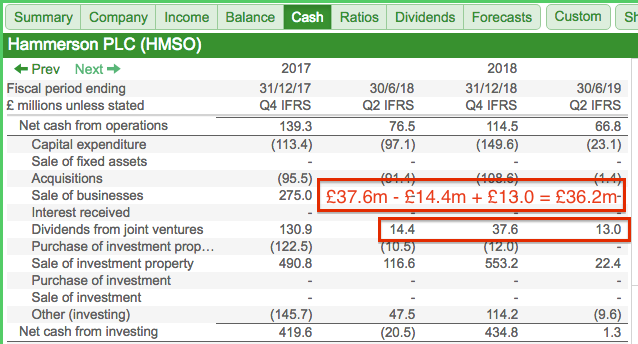

Hammerson’s cash flow is rescued by the contributions from its joint ventures and associates.

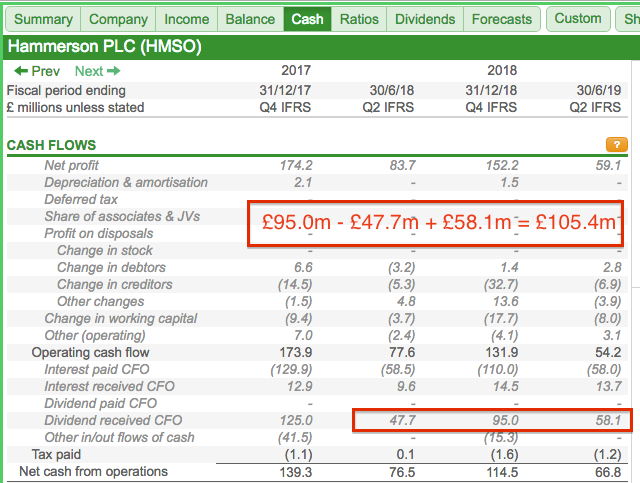

SharePad shows a total of £142m was received from joint- and minority-owned shopping centres during the second-half of 2018 and the first half of 2019:

Those contributions should help cover the interest payments.

However, the cost of maintaining the dividend to support that 12.5% yield is £200m or so a year…

…and yet operating cash flow (after interest payments) of £18m plus £142m from joint ventures and associates gives only £160m.

Oh, and these sums do not make any allowance for capital-expenditure commitments of £161m.

I now understand why Hammerson is so keen to raise money and sell properties below book.

But what I don’t understand is why the 11.1p per share/£85m interim dividend was sustained.

I can only presume the company reckons the payout can be funded by the upcoming disposals — which does not seem a sensible plan to me.

Summary

I did say the reality of price-to-book investing is not that simple.

Even with the steep share-price discount and the impressive dividend record, Hammerson is not an obviously great asset ‘bargain’. Instead, the apparent lack of immediate cash flow to service the group’s debts is rather alarming.

The group’s part ownership of certain sites — leading to some rather complex accounts — does not help matters, either.

I do wonder whether the stock market senses an upcoming rights issue. The last time the share price plunged this low — during the banking crash of 2008/09 — Hammerson raised a net £580m by issuing new shares at 150p.

Raising another £580m at 150p could reduce NAV to approximately 472p per share.

True, a rights issue would resolve Hammerson’s immediate cash flow issues. But it will not encourage tenants to pay higher rents.

And this is the crux of determining Hammerson’s NAV — the recent (lower) lease agreements have clear implications for other tenant renewals, longer-term income and the associated property valuations.

Finally, do bear in mind the talents of Hammerson’s management:

As well as:

* Deciding to focus on shopping centres in 2012, and;

* Declaring an £85m interim dividend in July despite stating the “absolute priority remains to reduce debt”…

… previous boardroom actions have included:

* Launching a £3.4 billion takeover of rival INTU during 2017, only to withdraw the offer a few months later due to “a heightened level of risk associated with the UK retail property sector”;

* Rejecting a 635p per share bid during 2018 because the price “very significantly undervalued Hammerson”, and;

* Approving a £129m share buyback at 460p during 2018 before suspending the purchases until the group saw “greater market certainty”.

With decisions like that — and the share price now close to 200p — perhaps the stock market is right to value the business at 30p in the pound.

Until next time, I wish you happy and profitable investing with SharePad.

Maynard Paton

Disclosure: Maynard does not own shares in Hammerson.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.