This month’s dive into the world of funds examines a high-quality way to invest in US equities, whose valuations are edging relentlessly higher. However, it’s not just US equities that are outperforming – after a prolonged period of underperformance, the share prices of many UK-listed alternative funds have pushed ahead. Buybacks are helping, and a landmark study by analysts at investment bank Panmure Liberum reckons there’s more good news to come in the listed private equity space. Sticking with private assets, we also look at a reasonably priced way to buy into private asset fund managers. And last but by no means, we wonder whether the real beneficiaries of the picks and shovels revolution behind AI might be energy utility firms.

Too much of a good thing in the US markets

Should you be worried that US equities are so exceptionally successful?

One of my favourite discussion topics when talking to investors is to get them to determine their actual underlying exposure to US equities, especially the Mag7. Add up what’s in your various portfolios, ISAs, your speculative positions, your SIPPs, and your DC target risk and target date funds. Unless you are nearing retirement, you probably have a much higher exposure to US equities than you realise—mainly because US stocks and shares have performed so well. Many long-term investment plans and global equity funds are benchmarked against an index called the MSCI ACWI index (with the MSCI World or FTSE World as alternatives). This index has 64% exposure to US equities, with Information Technology as a sector accounting for 24%, and the Mag7 making up just under 20% of the index. A close rival is the MSCI World index, which has nearly 72% exposure to US equities and just under 22.5% to the Mag7.

At this point, investors start to feel slightly uncomfortable. They’ll smile at the fact that returns have been excellent – even in recent weeks – but they’ll soon begin to worry about all the myriad risks in that exposure: the valuations, the concentration in a handful of stocks and the exposure to the dollar. Has the exceptional outperformance of the US (and its deep, liquid markets) created a risk to your portfolio?

Let’s be specific here: there are three interconnected but separate issues to consider. The first is whether overexposure to the US as a country and the dollar as an asset (which is currently weakening on the FX markets) is beneficial. Next is what we could call style risk for US equities, meaning whether I am overexposed to a specific type of US equity, such as tech stocks or growth stocks. The third risk is concentration risk, where you are concerned about being exposed to just a few stocks, specifically a suitably magnificent seven. It is helpful to distinguish these risks because, for example, you might be comfortable being overexposed to US assets, equally comfortable being overexposed to US tech growth stocks, but worried about putting all your eggs in the Mag7 basket.

Begin by considering concerns about overexposure to the dollar and US assets generally during Trump’s presidency. The dollar has been weakening (which is bad news for UK investors in US assets as valuations have dropped), and it could decline further (Trump would probably welcome that), but there is no evidence of a ‘flight from the US’ so far among private investors. Strategists at US investment bank Morgan Stanley recently analysed fund flow data on what foreign investors are buying and selling and found little sign of a widespread sell-off of US dollar assets. In fact, weekly data from Lipper on global equity ETFs and mutual funds show that international investors have been net buyers in the weeks following Liberation Day and throughout most of May.

But have we all – outside the US – become more exposed to its equity market? The short answer to that question is yes! In 2015, the MSCI ACWI index was only 51% invested in US equities; now it’s 64%. In 2015, Apple was the biggest stock (not Nvidia as it is now) with Microsoft not far behind at just under 1%. The price-to-earnings ratio of this index (a key valuation metric) was 18.50 back then. If we go back further to the year 2000, the US was at 48% (with the UK in second place at 8% exposure). So, is the US close to all-time highs in terms of geographic exposure? Yes, but not exceptionally so – and let’s be honest, if it is, that’s because US corporates have been growing their earnings at an above-average rate.

We can see this clearly with the S&P 500 benchmark index, which tracks US blue chips and has produced an annualised return of 12.8% over the last ten years. US profit margins are among the highest globally, which helps explain why the American index trades at a robust 27 times earnings, which is a somewhat excessive level, to put it mildly.

What about concentration risk or a bias towards specific sectors? Again, there are reasons to be worried, but let’s not get hysterical. The information technology (IT) sector is the biggest slug at 31% of the index, while the Mag7 comprise 32% of the value of the S&P 500 index. Technology’s share of the benchmark US index is high, but not amazingly high. As for concentration risk, if we look at the top ten stocks in the US index over the last century or so, all the way through to the mid-20th century, the top ten names have usually hovered around 20-30%, dropping below that level in the 1990s and 2000s, and then rising sharply in the last few years, reaching a peak of 40% in early 2025. And one sector has long tended to dominate the index – it used to be banks, now it’s tech.

So, what should you do? I’m more cautious about US equities than most and feel more comfortable running US equities at a closer to a 50 to 60% range in a portfolio full of equities. That’s what many successful global equities fund managers, such as the Alliance Witan Investment Trust, have been doing for a while now, notching US equity exposure to below 60%. Like many active fund managers, I’d be overweight Japan as well as the UK, which strikes me as cheap and provides valuable global diversification.

If you still want significant US exposure but seek more diversification, consider choosing a different style or type of stock within a fund. Instead of merely investing in a few tech giants, you could track US equities through something like the Invesco S&P 500 Quality UCITS ETF, which includes the 100 companies with the highest quality scores within the parent S&P 500 index. Alternatively, you might prefer cheaper, more value-oriented stocks and strategies. In that case, there’s an ETF from a firm called Ossiam that tracks an index devised by economist Robert Shiller – it’s called the Shiller Barclays CAPE index. This index (and ETF) still invests in big tech names, but it also tilts towards other well-known firms, with somewhat cheaper share prices, such as Eli Lilly, Costco, and Walmart. More generally, most active, stock-picking US equity fund managers tend to be biased against Mag7 stocks and more exposed to cheaper, value, and quality stocks, as they are more concerned about concentration risks and high valuations.

Oh, and if you think all this talk about US exceptionalism is just needless worrying, then why not go all in, bet on the coming AI transformation, and just buy the Mag 7 names, perhaps excluding Tesla and replacing it with Broadcom, another tech leviathan. One actively managed investment trust that embodies this ‘all-in’ AI-first strategy is the Manchester and London investment trust, which essentially represents a substantial bet on Nvidia and Microsoft (64% of the portfolio) alongside Broadcom and Arista, two other AI-related companies (another 12.5% of the portfolio). Two tech investment trusts, Polar Capital Technology and Allianz Technology, are also betting big on AI and on US tech, but with a more diversified portfolio, which even includes some international names.

Buybacks seem to be working for listed PE and VC funds

The UK investment trusts sector has had a torrid time in recent years, especially for alternative funds, but the outlook is improving. M&A-driven capital recycling and reduced selling pressure have supported secondary demand. Discount tightening is increasingly broad-based, signalling a shift in sentiment.

|

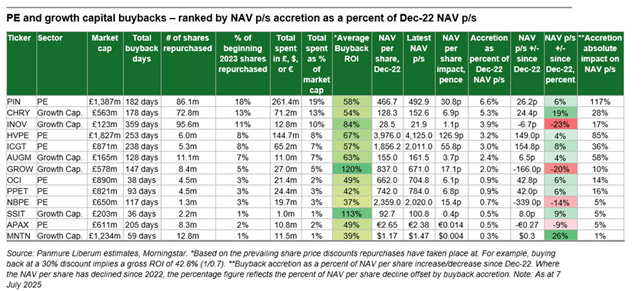

One notable trend has been the increased use of buybacks by investment trust boards. Repurchases have significantly contributed to NAV returns for growth capital and PE funds, especially in a lower return environment. Income funds also conserve cash on dividends. But have buybacks generally been effective for investment trusts, and have they helped boost share prices? Panmure Liberum’s alternative funds analyst Shonil Chande believes so, but with some caveats. He suggests – in an incredibly detailed study – that while buybacks deliver stronger early returns, their advantage diminishes unless discounts stay consistently above 40. He also thinks buybacks are most effective not for income-focused funds but for those seeking capital growth with internal rates of return above 10% per annum (think VC and PE funds). According to Chande, the return on investment calculations behind buybacks are clearer for capital-growth vehicles. For PE funds, in particular, portfolio returns have been significantly lower over the past two years, and buybacks are providing a useful lever for NAV growth during this tougher cycle. “Comparing the most recent NAV per share with figures from the end of 2022, we see that repurchases have been a core contributor to NAV returns for growth capital and PE funds. This accretion is especially significant for NAV growth-focused vehicles, particularly in a lower return environment for core portfolios. For example, HVPE’s buyback activity has contributed around 126p of NAV per share accretion, accounting for approximately 85% of its total NAV per share growth since 2022. CHRY and OCI are also noteworthy. CHRY is just over 70% through its £100m capital return programme, which has added about 7p to NAV and very likely helped push up the share price. OCI has been spending a very substantial amount on its buyback days, with a strong impact so far.” |

In some instances, the use of buybacks has been a wasted opportunity, particularly when performance has been ordinary and/or the share price rating is at a discount to peers. One year after seeding its €30m buyback pool, Apax Global Alpha has deployed less than £11m (spending just c.£50k-£60k per day), and the discount to NAV has widened significantly, highlighting that the cautious pace of execution failed to capitalise on earlier opportunities and left the fund more exposed to deteriorating market sentiment. For buybacks or any capital allocation strategy to be effective, conviction and timely execution are essential; otherwise, the impact is weak. A diluted approach to capital allocation, such as underutilising a buyback pool, or spending that is too low a proportion of daily volume/liquidity, has little impact.”

I’d add that there are almost certainly many more buybacks coming in the listed PE and VC sector – watch this space and do some research on Molten Ventures.

A private assets vehicle that’s still reasonably valued: Petershill Partners

Two forces are reshaping the global equity and bond markets: the first is the rise of the passive, index-tracking fund, most frequently encountered through an exchange-traded fund (ETF). These ETFs are helping to lower the cost of investing whilst also intensifying momentum flows into sexy, fast-growing tech stocks.

The other force is the move to private markets, most notably through private equity funds but also through private credit and other financial structures involving non-listed, privately owned businesses. An ever larger share of money from investors is being directed to private asset funds, and that’s meant a boom for private asset fund managers.

So, while most listed equity fund managers, such as Jupiter, Schroders, or Polar Capital, have seen their share prices struggle in the face of intense pressure from ETFs, private asset managers are emerging all over the place. That represents a big business opportunity for private investors: how to invest in this growth sector? One way is through a slightly unloved, London-listed business called Petershill Partners.

Investors invested $1.4 billion in the Goldman Sachs-managed Petershill when it first floated at 350p back in September 2021. The business was intended to serve as a ticket into the rapidly expanding world of private asset market money managers, offering equity stakes and investments in the underlying funds of various managers.

Petershill focuses on mid-market, management-fee-centric alternative asset managers. These assets include a stake in Clearlake Capital, which is best known in the UK for its ownership of Chelsea Football Club. The shares spent the first year or so heading steadily downward, dropping as low as 145p as a dearth of private equity deals soured sentiment. Since then, sentiment has improved, and the shares have stormed ahead. That said, even after a 35% increase in the share price over the last year, the shares still trade at a 39% discount and yield 5.1%, up over 1 year by 35%.

Sentiment has been bolstered by both decent operating numbers and recent deal flow: the most recent deal was the sale of the majority of its stake in a business called General Catalyst. The total nominal consideration of $726 million represented a 62% premium to the $447 million carrying value as of June 2024. A special dividend of 14.0 US cents per share (US$151m) has been declared.

As for recent results for the financial year ended December 31, 2024, partner distributable earnings rose by 11% to US$323 million, driven by strong fee-related income, realisations at premiums to carrying value, and an active year for capital allocation. Assets at portfolio firms rose to US$337bn, while fee-paying AUM was up 8% to US$238bn.

The company completed four acquisitions totalling US$205m and three disposals generating US$575m of nominal consideration during the year, returning a total of US$563m to shareholders, including US$287m in special dividends, a US$103m tender offer, and a US$6m buyback. Book value per share rose to 471 US cents (2023: 431 US cents). Disposals during the year were completed at an average premium of 19% to the last reported carrying value. For 2025, the company is guiding towards:

– US$20–25bn in new fee-eligible AUM

– US$180–210m in partner FRE (2024 pro forma: US$186m)

– PRE to comprise 15–30% of total partner revenues

– Acquisitions likely to exceed the medium-term range of US$100–300m

Shares in Petershill Partners have recovered from their lows back in 2023 (the low price hit a shade above 140p) and now trade at 236p, up 8.6% for the last year. But that recovery has stalled in recent months (the shares are actually down 1% year to date), and the business remains reasonably valued on a discount to Nav of 34% on a forecast dividend yield that’s roughly around 5 to 6% per annum, depending on the forecast.

AI and Energy

For me, there’s a deeper story lurking behind the AI and Data Centre capex build-out: the much-debated energy transition. Once you build a data centre and spend all that money on Nvidia chips and copper wire, the primary variable cost element is energy. Lots of it, 24/7. Reliably and with no intermittency, and preferably as green as possible.

Morningstar has just released a report arguing that AI-dedicated data centres will increase from 25% of data centre capacity at year-end 2024 to two-thirds by 2030. They project that data centre power capacity will need to increase to approximately triple, to 80 gigawatts, by 2030. Where that extra power comes from is a matter of debate. According to Morningstar, most incremental demand (60%) will be met by natural gas, given its ability to provide baseload power. This will be supported by renewable energy additions (25%) and select restarts and expansions of existing nuclear capacity (15%). They don’t see new-build nuclear (including small modular reactors, SMRs) as a viable option until the early to mid-2030s.

But that massive upsurge in spending on data centres is occurring at exactly the wrong moment. Most existing legacy electric grids are already struggling with two separate but related structural drivers: the need to decarbonise the grid and the need to provide a more decentralised grid that can cope with everything from intermittent wind turbines to electric cars powered overnight. Those structural drivers, in turn, are powering existing policy debates: local or zonal pricing for power, or whether we’ll meet the Clean Power 2030 deadline (I don’t think we will).

Overlaid on these challenges is an even more fundamental issue, highlighted by the recent power station outage at Heathrow – much of our existing power distribution infrastructure is outdated. So add it all up and we have multiple transitions all at the same time: extra AI data centre demand; more intermittent power from renewables; the need to provide more decentralised power availability; demand for more power generally as we decarbonise. This all suggests a massive investment boom, which will require the big utility firms to spend an enormous amount of money. They won’t do that unless they receive a decent return on their equity and debt.

This presents both opportunities and risks for the utility firms. The risk is

- Not expanding enough to meet demand, producing supply shortages

- Too much debt and not enough equity

- Regulators tighten the screws and force down revenue growth

The upsides are also obvious :

- Extra revenue

- The regulators do allow a decent return on capital

- New services can be provided to business owners, for instance, wanting a constant, uninterrupted, green power supply

A recent research paper by analysts at Deutsche Bank adds some details to these thoughts. It presents what I believe is a compelling case for investing in utility firms, in general, and European utility firms, specifically. In simple terms, if you think the upside will be rewarded, then existing valuations on European utilities are low.

- In the U.S., the average regulated utility’s rate base is projected to grow at 6%-8% annually through 2030 according to some analysts’ forecasts and similar growth has recently been observed in European countries such as Germany, Spain and Italy.In the U.S., the average regulated utility’s rate base is projected to grow at 6%-8% annually through 2030 according to some analysts’ forecasts and similar growth has recently been observed in European countries such as Germany, Spain and Italy.

- There are price premiums in some markets for clean power – in the U.S., according to a survey by Morgan Stanley, corporate buyers are paying an average premium of USD23 per MWh for firm, carbon-free power, while in Europe, the premium stands at USD18 per MWh.

- While gas-fired power plants typically take 5–7 years to build, renewables can be deployed in 1–2 years, allowing for much faster capacity buildup. As the cost gap between solar/wind and natural gas power generation is narrowing due to rising capital costs and longer wait times for gas projects, renewables are becoming for utilities a more attractive option even without tax credits. Additionally, hybrid solutions combining solar with battery storage and grid connectivity are becoming more viable, providing flexibility and speed to market advantages.

- In the U.S., annual capital expenditures by utilities are expected by analysts to have surpassed USD180bn in 2024, a 9.5% increase from 2023 and a 26% rise from 2022 levels.

- In Europe, utilities have been revising their capex guidance upward to reflect increased grid investment requirements, with some firms increasing capex budgets by 25% or more.

- By the end of 2024, the Utilities sector was trading at an average forward P/E multiple of 11.9x in Europe, a meaningful discount relative to historical levels (-16% vs 10-year average). The sector’s P/E multiples for European and U.S. Utilities currently stand at 12.9 and 16.8 respectively, below 10-year median values for the Stoxx 600 Utilities while aligned with historical values for the S&P 500 Utilities sector.

- On average, analysts forecast EPS growth of 7.7% and 7.5% for U.S. and European Utilities for the upcoming 3-5 years, above average EPS growth for the past 20 years (~5.5% for U.S. and European Utilities).

In my view, the best way to play this is through a diversified, specialist utility equities fund, such as Ecofin Global Utilities and Infrastructure. This fund has long appealed to defensive, income-oriented investors and boasts an excellent track record. In performance terms, for instance, it has consistently outperformed the MSCI World Utilities Index over most commonly used periods, including one, three, and five years. Recent performance has been excellent – up 25% year-to-date – but I believe the long-term upside is significantly greater. I also like the fund’s focus on European utilities amongst its top ten holdings.

Fund Facts: Ecofin Global Utilities and Infrastructure

· Discount 9.1%

· Five-year NAV returns 65%

· YTD up 27% share price, NAV 18%

· Yield 4% or 8.5p pa

Top Holdings

- Vistra 5%

- National Grid 4.8%

- Vinci 4.7%

- Enel 4.4%

- E.On 4.1%

Another way to play the power transformation theme is through a well-established listed infrastructure fund, such as INPP (International Public Private Partnerships). Alongside more traditional PPP and PFI assets, INPP has an extensive portfolio of power infrastructure assets, including power transmission lines, and now nuclear power!

INPP has committed £250m, split into five annual tranches of £50m, into Sizewell C’s regulated company in return for a 3% shareholding. This comes alongside the UK government’s commitment of £14.2bn over the current Parliament, the Nuclear Liabilities Fund, La Caisse (formerly CDPQ), EDF and a £1.3bn investment by Centrica.

INPP hasn’t released data on the returns expected from this deal. Still, co-investor Centrica has stated that the return on equity is expected to be around 10.8% per annum through to 2039. INPP has noted that the asset is expected to deliver an attractive, fixed rate of return during the construction phase (including a cash yield from financial close) and a low-teen IRR is assumed until the late 2030s. Thereafter, during the operations phase, regulated returns and incentives will be set by Ofgem at 5-yearly periodic reviews. INPP has also said that the commitments to Sizewell will principally be funded with the proceeds from the ongoing divestment of lower-returning assets, which the company currently owns.

As analysts at Investec note, this deal is a higher-risk deal in a sector notorious for delays and cost overruns and “investors must be comfortable with the expected evolution in the risk profile”. However, based on current valuations, I believe INPP represents a very decent value with a well-supported dividend yield.

~

David Stevenson

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from David? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for ‘share chat’

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.