This week, Jamie talks about the narrow education professional investors receive and why it is important to keep learning. He then discusses why you can make a compelling case for Burberry yet he does not own it currently as he puts into practice the lessons he’s learned later in his career.

When I passed my driving test as a teenager, I remember my dad saying that it’s after you pass your test that you really learn to drive. He wasn’t besmirching the skills of my driving instructor, a man called Mick Ward (no relation) who endlessly told the same four jokes. Rather he meant that you needed experience in real-world driving, alone, and away from the artificial environment of a learner car to really understand how to act and react to driving conditions.

If only the investment industry had more people like my dad in it, then there might be a little more humility among the wunderkinds. Alas, for about twenty years now, the standard educational path was some sort of numerical degree followed by CFA. In fact, this was my path into the industry (Maths degree FYI). It provides a tremendous grounding to start understanding all aspects of investing. My own preference and career path was towards the equity market, but it could have just as easily have been another area like fixed income derivatives for example.

However, as with driving, it’s only when you begin applying what you’ve learnt to the real world, do you truly learn the craft of investment. I think this is why the majority of equity analyst job adverts out there are looking for freshly qualified CFAs who are not too experienced. This is so that the prospective employees have sufficient grounding but can be moulded according to a particular company’s style.

Anyhow, where this very common pathway is hugely beneficial, is helping people become highly skilled fundamental analysts. A fundamental analyst is one that weighs up the various pluses and minuses of a potential investment to make a considered investment decision. I’ve never seen the purpose of fundamental analysis summed up better than in my first ever job by my first boss, Kevin Doran. He used to say that, with each investment decision you are assessing, are you being properly compensated for the risk you are taking?

In effect, this means that the act of investment analysis is an attempt to divine the likely rate of return of an individual investment. It is then a subjective judgement call on whether that rate of return is at least commensurate with the risk being taken. The beauty of this framework is that it can be used on virtually any prospective investment from common equities to rental properties to obscure ETFs. Indeed, Ben Graham, the father of investment analysis would’ve argued that anything short of this was not an investment at all, but rather a speculation.

So far so sensible, however, there is a problem with this approach taken as the entirety of the decision matrix. That is, it doesn’t matter how much analysis you do you will always end up not knowing everything. In fact, excessive amounts of analysis often lead to paralysis by analysis, whereby a decision is never made because so much importance is placed on increasingly obscure points. Think of a fractal, the job of analysis is to gain a clear picture of the overall image, however, overly deep analysis leads to a detailed inspection of each tiny strand and loses the fundamental point.

Now for a contradiction. Sometimes small details can turn out to be very important and it is difficult to discern the emergence of this importance. And so as fundamental analysts, we have a problem, we need to understand the big picture and not get too bogged down with detail but sometimes, the detail is the big picture.

As I matured as an investor, I realised that it was a fool’s errand attempting to understand every strand of the fractal. This led to a greater appreciation of other aspects of investment so that I, as a mathematician by education, began to appreciate that investment was at least as much an art as a science.

Because of the aforementioned typical route to professional investors, what investment analysis means has become rather narrow insofar as it emphasises the science of the craft and eschews the art. You can sort of see why because it is easier to conceptualise scientific thought but art, by its very nature, is much more difficult to systematise.

Technical Analysis

Many in the City are rather sniffy about technical analysis as a manner to select investments and, from my experience, the older one is, the more open to it they are. I think the reason is that older city types pre-date the formal ‘this is how analysis is done’ mantra. I won’t go into detail about what technical analysis is (here are some good places to start, here and here), but rather state that it is the use of price data and data related to security itself rather than the underlying fundamentals of the business. It is often best-known offshoot is charting, where by a share chart is considered to contain much of the information about the strength of an investment.

I remain a fundamental analyst at heart since I rely heavily on my understanding of a business over and above anything else. However, an innate sense begins to permeate in one’s investment decisions as one becomes more experienced. That occurs when you can make a strong case for the fundamental merits of an investment yet, it doesn’t feel right; the shares are not behaving as your analysis should dictate. Over time, I began to appreciate that the share price frequently reflected a reality that my analysis, however sophisticated, could not.

On Market Efficiency

There is a concept in markets called the efficient market hypothesis that states that everything that a share price reflects everything knowable and known in a company. To be an active investor is to believe that markets can’t be completely efficient else there would be little point in security selection. Nevertheless, it would be foolhardy to believe that share prices don’t at least partially reflect reality. This partial reflection of reality is what can lead share prices to trend. That is to say, an emergent property of a company slowly becomes apparent over time as various fundamental factors impact a company and are gradually assimilated into the big picture.

As a fundamental analyst, it is impossible to be on top of every emergent trend and asses its importance i.e., one cannot keep an eye on how every tiny branch of the fractal is evolving. But because of the partial truth of the efficient market hypothesis, one can see that emergence in real-time simply by observing share prices. Therefore, a well-rounded investor should know a great deal about the company in which they have invested, but realise that they can’t know everything and some level of technical analysis can enhance an investor’s process.

In this way, the use of fundamental analysis is your rational brain interpreting truth in numbers. Whereas technical analysis is a tool for tuning into what your heart is telling you. Fundamental analysis is a critical component of my investment journey but when it comes down to whether you are going to buy or sell something, trust what your heart is saying and pay attention to technicals.

Why I don’t Burberry now

When Patrick and I ran the fund, one of our investments was Burberry. It fitted in our process quite well since we believe it was a business that could compound value over time. In essence, it was considered ‘quality’ (more on the dangers of the ‘quality’ moniker in the next article). However, both of us had a slight niggling feeling with Burberry owing to it being a single-brand luxury goods operator that was always one or two missteps from a very nasty time indeed. Some of the readers know both Patrick and I and would attest to neither of us being the target market for Burberry (or anything else for which the term ‘luxury’ is used). Thus, whilst we held it as part of a portfolio, we were always keen to ensure that the position size remained modest – an admittance that there are some things we know we don’t know.

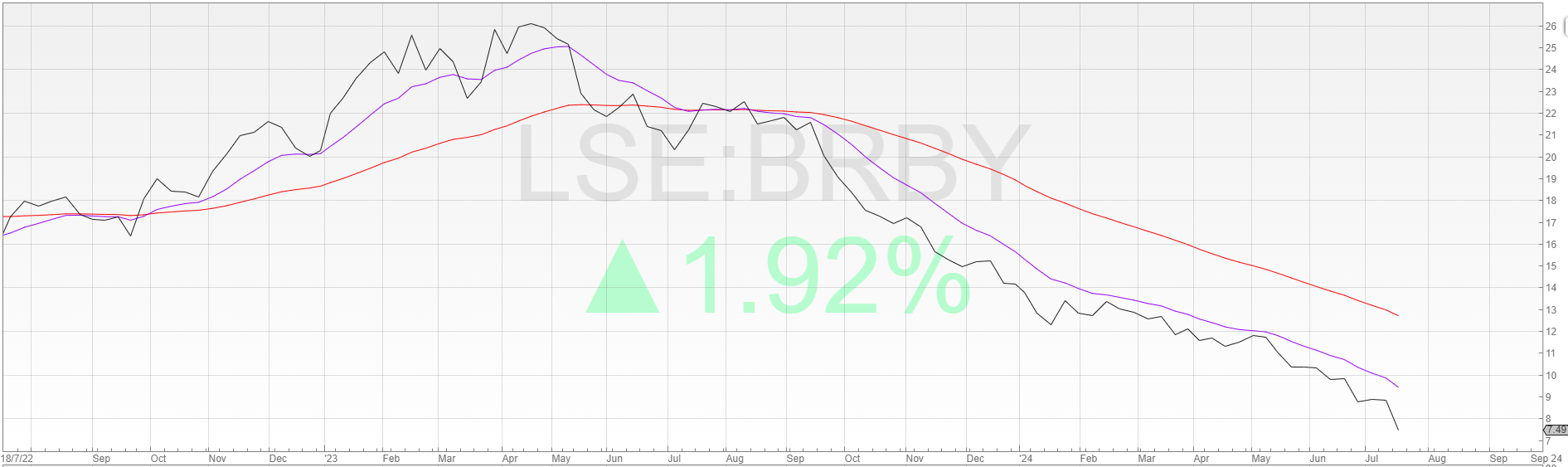

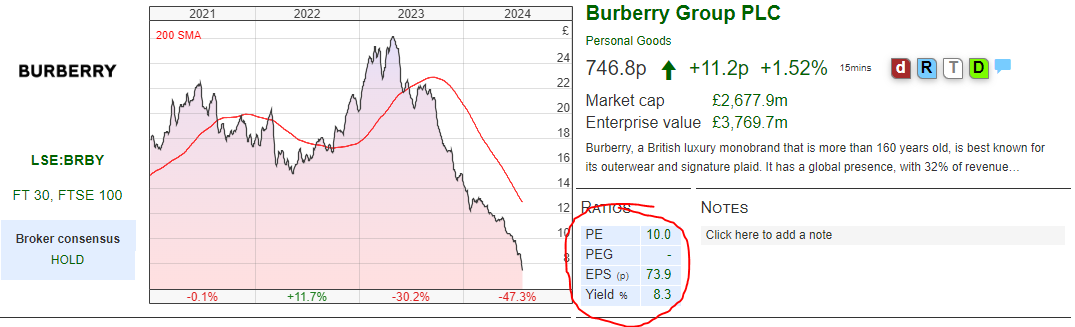

As it happens, we did rather well in the shares, having bought it around 1200p and sold it >2000p. It is now more than three years since I last owned the company, during which time the share performance has been woeful. Naturally then, as a value investor at heart, it has begun to pique my interest once again.

The psychological concept of anchoring is dangerous in investing if you are not aware of its influence on yourself. Given our success in buying the share at c. 1200p, I naturally started becoming interested at these same levels. Ten years ago, at 1200p I might have concluded, ‘Wow, that’s cheap and it’s pretty good business’. Clearly, the business is going through a shaky patch but 1200p worked as an entry in the past so why not now?

The fundamentals looked fineish at 1200p and the valuation was very compelling but the share price trend was telling a different story. The relentless negative performance, which was trending sharply lower indicated the presence of an emergent trend that would be very difficult to detect fundamentally.

In the intervening four months, the share price continued lower, losing a further 30% on no news. Only when the company released a trading update on July 15th did we see in black and white what the share price was already telling us. The company’s problems are bigger than indicated at the time of the January update.

You can argue that the share price reaction on July 15th was the entirety of the news being assimilated but I’d argue that the fall from 1200p to the current 750p, a much greater percentage loss overall was the result of the company deteriorating over the period with the actual release of the trading update was an unpleasant punctuation mark.

I still think Burberry is a decent business, but these days I want to see the share price beginning to reflect a change in conditions before I commit to investing, which hopefully allows me to continue to avoid things like Burberry in the last six months where apparent cheapness led to a near 40% decline. Today, the shares look cheap (really cheap) and my head says it could be a good investment but my heart says not yet.

Jamie Ward

Jamie doesn’t own shares in Burberry.

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Jamie? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.