Active exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are all the rage at the moment in funds land and may overtake investment trusts in the not-too-distant future. Crucially big, well-known names in fund management are lining up behind the idea. We dig a bit deeper. Plus, a deep dive into the world of Japanese benchmarks and funds.

Active ETFs are coming for a platform near you

Over the last two years, there have been no – zero – new investment trusts. Over the same time period, there have been hundreds of new exchange-traded funds and dozens and dozens of active ETFs. As I intimated in a recent Financial Times article, the latter listed fund (an active ETF) looks and feels a bit like an investment trust and very soon might replace the venerable investment trust. One big development is that major fund managers such as Robeco on the continent and Fidelity in the US are embracing active ETFs with a passion – we’ll look at some new launches from them a little later in this article. That said, some crucial differences and similarities between an active ETF and an investment trust need explaining. To make things even more complicated, there are some big differences between a traditional, index-hugging ETF and a shiny new active ETF.

The first point is that an active ETF differs from a traditional passive ETF in one very important way. In the latter, a fund manager identifies an index, such as the FTSE 100 or the S&P 500 and then replicates or tracks that index passively. If Nvidia suddenly doubles as a holding in the S&P 500 because of rocketing valuations, then the passive fund will track that change.

An active ETF might still have an index or benchmark, but its explicit focus is on actively beating the index through its portfolio of active stock or bond picks. In a sense, this is exactly what an actively managed investment trust also seeks to do – if we look at Witan Alliance Trust, it too chooses to reference an index, a global equities index, and then aims to beat that index. So, there is an obvious similarity in investment strategy between an active ETF and an investment trust. Another similarity is that both investment trusts and ETFs are listed funds, i.e. they have a ticker with a real-time quote for buying and selling shares all day, every day (when the markets are open). That makes them very different from unit trusts, which only issue an end-of-the-day price for underlying holdings which then triggers any buy or sell orders.

However, the similarities between an ETF and an investment trust stop there. Both a passive ETF and an active EF are open-ended fund vehicles (like unit trusts), which means the manager can issue shares regularly – in fact, daily or even in real-time if they so choose. By contrast, Investment trusts are closed-ended vehicles, which means they start with a fixed issuance of shares. That doesn’t mean that the fund can’t issue new shares via a placing programme for instance, or buy back shares regularly, as many investment trusts are doing – but they don’t have quite the same flexibility to change the amount of shares in issue.

The next big difference is the passive and active creation and redemption process in ETFs. This mechanism allows the ETF to trade at close to, or exactly at, the shares’ net asset value. In this complex process, the fund manager issues shares based on the portfolio holdings, which are fully transparent in real-time (in the US there are semi-transparent ETFs but let us ignore that for now). This list of holdings is available to a market-making authorised participant firm, usually a financial intermediary, which can then look at the index and compare it to the fund holdings. If the fund’s assets are worth, say, £100m, but the value of the fund is only £95m, for argument’s sake, the AP can buy the shares and then exchange these shares for a basket of securities ‘in kind’, or vice versa.

The AP can create and redeem shares based on an agreement with the fund issuer. If there is a shortage of ETF shares in the market, the AP can create more ETF shares, and again, this works in reverse as well – they can redeem shares. It all sounds complicated, but the key impact is that there should be a close match between the fund’s net asset value and the ETF share price. This doesn’t mean that an ETF can never trade at a discount to its NAV (or premium), which does happen in some instances with some exotic investments, but for the vast majority of the time, there should be no discount or premium for an ETF. Crucially, this mechanism works for active ETFs as well – instead of an index, we have a model portfolio or basket of shares equivalent to the fund holdings.

Investment trusts operate in a very different way. Discounts are common in the closed-end fund space, and although managers and boards can use all sorts of mechanisms to close the gap (buybacks and tenders, for instance), many of these don’t move the discount appreciably.

Another key difference between trusts and active ETFs worth noting is cost and structure. It’s very easy to create an ETF because there is no board of non-executive directors or NEDs, and the fund structure is simplified and streamlined based on a common set of European-wide rules set mainly by Ireland and its central bank under the regional UCITs framework. No sponsoring broker officially launches or IPOs the fund as an adviser, which also helps cut costs. Crucially, suppose you are an active fund manager. In that case, you can probably issue an ETF with just a few million pounds in assets under management and then slowly build it up in scale – most analysts reckon break even for an ETF is probably somewhere between £10m and £50m. And that’s true even though most ETFs charge less than 0.50% per annum in total expenses which is much lower than the equivalent investment trust. The Janus Henderson Japan equities fund, for instance, charges 0.49%. In contrast, most Japanese investment trusts charge between 0.50% and 1% – according to Numis, the average large-cap Japanese equities fund charges 0.81%, while the average small-cap Japanese equities fund charges 1.1%.

Now, it’s important to step back at this point and say that the extra structures in place with an investment trust may cost more – you need to pay those directors and broker advisers – but they also provide real protection for investors. If the fund manager underperforms, the board can fire them and find a new manager. That isn’t the case with an active ETF. A closed-end fund structure also provides permanence – this is a long-term commitment of capital unless the fund decides to wind up. With active ETFs, you can start with a few million pounds in assets under management and then remain under the radar for years, not attracting much capital or research interest. Many active ETFs close in the US because they fail to attract much interest and the manager can just decide to close down whenever it suits them – although you will receive your net asset value per share back when the fund closes.

Active ETFs vs Investment Trusts

|

Active ETF |

Investment Trust |

|

|

Listed on a stock exchange |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Open-ended with creation and redemption daily |

Yes |

No |

|

Closed-ended permanent vehicle |

No |

Yes |

|

Has a board of non-executive directors |

No (1) |

Yes |

|

Has a broker/sponsor |

No |

Yes |

|

Likely to feature in fund analyst research reports |

No |

Yes |

|

Likely to trade at a substantial (10% or more) premium or a discount |

No |

Yes |

|

Manager will refer to a benchmark index for performance analysis |

Yes |

Yes |

- Active ETFs may have an ultimate holding company for UCITs rules which will have a board of directors

A gaggle of interesting new active ETFs (that could have been investment trusts)

With this explanation out of the way, one of my big predictions for 2025 is that we’ll see a veritable tsunami of active ETFs, many of them in the core broad equities space – and many of which would once have been an investment trust.

The first is from the big European quant finance asset manager Robeco, which has built a very solid reputation for its pointy head analysis. It just launched a gaggle of ETFs in the London market based on well-established quantitative enhanced index capabilities (3D ‘Global’, ‘US’, and ‘European’ Equity ETFs). In particular, the ‘Dynamic Theme Machine’ ETF invests in established and emerging investment themes, capitalising on Robeco’s cutting-edge next-gen quant research.

So, why look at Robeco? Two reasons stand out. If you are going to track a broad asset class like global equities, your benchmark index really matters. There are, in fact, a range of global equity benchmarks, all with different characteristics. Picking the right index is tough, which is where Robeco comes in. Their core skill base is in quantitative finance, and they specialise in building smarter benchmarks.

Their other skill base is in taking that quant expertise and overlaying varying themes and trends into this benchmarking exercise. They also add in hedge fund-style quant strategies to maximise returns—these are strategies usually only open to big institutional fund buyers.

Stepping back from all the technical jargon, you will hopefully get a more intelligent, sleeker global equities tracker fund. So, rather than buy a plain vanilla MSCI World equities tracker, you buy an actively managed ETF that looks and feels like a global equities tracker but has lots of ‘special’, quant-driven features based around maximising positive momentum and minimising risk.

Or as Robeco itself says, “Robeco’s 3D ETFs build on 20 years of experience with enhanced indexing strategies which have consistently performed well. Investors increasingly weigh up sustainability in their investment decisions, but finding the right balance between risk, return, and sustainability requires the right approach. Focusing solely on sustainability could limit return potential while ignoring sustainability could expose the portfolio to long-term risks. Here’s where Robeco’s 3D approach uses an optimisation process that aims to balance all three dimensions at once – a portfolio is created that dynamically searches for the best possible trade-offs between them, based on pre-set targets and real-time market conditions.”

Robeco’s Dynamic Theme Machine ETF takes a slightly different approach. It uses Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to identify emerging investment themes early.

“This ETF dynamically adjusts its portfolio to capture growth opportunities ahead of the market, setting it apart from traditional thematic ETFs that often focus on well-established themes. It uniquely addresses the challenges of traditional thematic ETFs by identifying emerging themes before they become crowded, and dynamically adjusting the portfolio over time. The strategy employs advanced algorithmic techniques to process large amounts of data to identify new themes and relevant stocks. “

I realise it all sounds a bit jargon-heavy. Still, these ideas are prevalent among institutional investors (and hedge fund investors), and making the strategies accessible to UK investors on a retail platform is a big move forward. Robeco has a first-class reputation among financial analysts for the thoroughness of its research. Their only real competitor is the US asset management shop AQR, run by legendary strategist Cliff Asness.

Robeco’s active ETF lineup:

- Robeco 3D Global Equity UCITS ETF (3DGL)

- Robeco 3D US Equity UCITS ETF (3DUS)

- Robeco 3D European Equity UCITS ETF (3D3D)

- Robeco Dynamic Theme Machine UCITS ETF (RDYN)

Fidelity is another well-known, highly reputable fund manager jumping aggressively into the active ETF space. They are pushing a slightly different idea than Robeco. Rather than focus on top-down, global equities in a fund, Fidelity is focusing on particular styles of investing, i.e., value, quality, momentum, and growth.

These investing styles are fairly well established but talk to most equity-focused finance professionals, and they’ll probably say they like a combination of quality investing but at a reasonable price (value overlay). This is probably the classic active fund manager strategy, and it’s coming to ETFs via active funds. Fidelity already has a suite of active ETFs that focus on one specialist bit of this strategy space: quality income ETFs.

Building on those funds, Fidelity is now launching another two ETFs: The Fidelity US Quality Value UCITS ETF and Fidelity Global Quality Value UCITS ETF which will form the initial part of the firm’s new Quality Value ETF range.

Fidelity’s in-house approach is “to improve the value definition to account for certain intangible assets, such as Research & Development, to avoid value traps by focusing on quality stocks while controlling sector and country exposures relative to the broad market. The new ETFs will track the Fidelity Quality Value Index family, …. to reflect the performance of stocks of large and mid-capitalisation companies that exhibit attractive valuation, ESG characteristics and specified investment quality attributes.”

|

Ticker |

Product |

ISIN |

Headline OCF |

Discounted OCF* |

Benchmark |

|

FUSV |

Fidelity US Quality Value UCITS ETF |

IE000MKIH0W7 |

0.25% |

0.20% |

Fidelity U.S. Quality Value Index |

|

FGLV |

Fidelity Global Quality Value UCITS ETF |

IE0002XFS025 |

0.40% |

0.30% |

Fidelity Global Quality Value Index |

- note that the Discounted Ongoing Charge Figure (OCF) includes a fee waiver by the Fund Management Company, which is applicable for the first 6 months from the date of the ETF launch or for the first $500 AUM million per ETF. Please note that the headline OCF will not change, but the Fund Management Company will collect a reduced fee during the specified period or threshold.

Japan indices and funds

It’s not only the US equity markets that have enjoyed a fantastic 2024 so far – Japanese equities have also been on a roll. While the US benchmark S&P 500 index is up just over 27% year to date, the Japanese large-cap index, the Nikkei 225, is up over 17%. It’s not all been plain sailing, with the recent surprise Japanese election puncturing some of the bullish sentiment, but the Japanese economic fundamentals look promising. It’s a strong export economy, with a resurgent consumer sector benefitting from decent wage rises (after many decades of deflation). Japanese corporates have also aggressively deleveraged and increasingly embraced Western-style corporate governance. Last but by no means least, Japan is also a big player in the semiconductor and robotics space, with fast-growing businesses such as Fanuc and Keyence popping up in many growth investors’ portfolios.

The challenge though is to understand how to invest in this important market – the second largest market in most global equity indices and much bigger (by market cap) than the London market. The first step is to understand the benchmarks that are used by many fund managers, both passively through exchange-traded funds and actively via investment trusts.

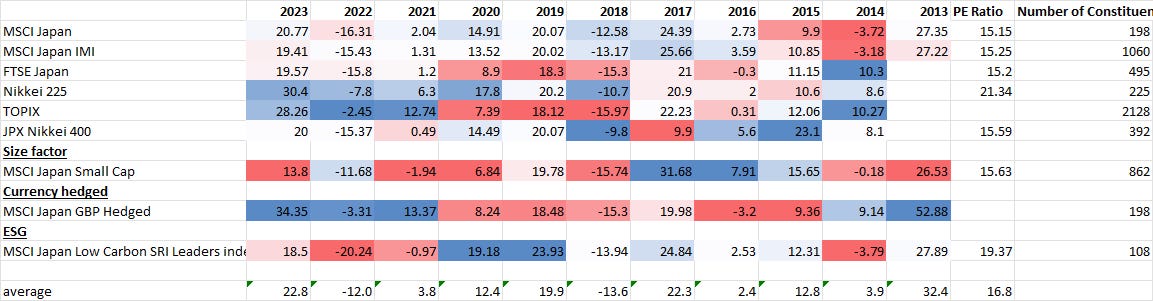

Let’s start by looking at the first table below. This heat map shows yearly returns for the main Japanese broad equity indices. The biggest pool of money is in the MSCI Japan index – you’ll see two versions of the index, the plain vanilla MSCI Japan index, and the IMI version. The main difference is that the IMI index – the MSCI Japan Investable Market Index (IMI) – is designed to measure the performance of the Japanese market’s large, mid and small-cap segments. The index covers approximately 99% of Japan’s free float-adjusted market capitalisation. By contrast, the MSCI Japan index comprises just 198 stocks, which covers approximately 85% of Japan’s free float-adjusted market capitalisation. Put simply, the MSCI Japan index is a narrower cross-section of the market, whereas the IMI version is much broader – and is more widely used by ETFs.

The main rival to the MSCI index family is the FTSE Japan index. This Japanese equities index uses a market-capitalisation-weighted methodology and is designed to represent the performance of Japanese large—and mid-cap stocks.

You’ll also see extensive media coverage of the Nikkei 225 index, arguably the most high-profile stock market benchmark. Many fewer ETFs track it, and that’s for a very good reason: it’s a poorly structured index. It is a price-weighted index operating in the Japanese Yen, and its components are reviewed twice a year. That makes it similar to the Dow Jones Industrial Average index, which I also heartily disapprove of. Price-weighted indices are open to weird distortions and should be avoided at all costs!

The TOPIX index is another hugely popular index, although only a handful of ETFs use this index. The TOPIX probably claims to be the most popular index amongst private Japanese investors. It comprises two sections: the First Section contains the larger companies in the index, while the Second Section comprises smaller companies. Because of its nearly 2000 constituents, TOPIX is widely regarded as the most diverse, broadest benchmark for Japanese stock prices. It is also a free-float capitalisation index. This means that the constituents are weighted not only according to outstanding shares but also by those freely available for trading. Many Japanese firms have cross-holding with their strategic partners, hold stock in these partners and rarely, if ever, trade it. Hence, those shares are out of circulation and not available for trading. Only the free float shares, or investable shares, are used to calculate the capitalisation of TOPIX’s member constituents.

Last but not least, you might have seen a relative newcomer in the index space, the JPX Nikkei 400 index. This is an innovative, market cap-weighted index that incorporates a number of important screens. The index itself describes it as a new “index [that] will promote the appeal of Japanese corporations domestically and abroad, while encouraging continued improvement of corporate value, thereby aiming to revitalise the Japanese stock market. It screens stocks on the main markets for various fundamental measures such as return on equity and corporate governance (boards sue non-executive directors). I think this has the makings of a great index and is worth watching closely – on average, it is also much the cheapest of the indices using historic price-to-earnings ratios.

The heat map below fleshes out annualised performance for these various indices.

What’s immediately obvious is that there has been a very significant variation in returns on a year-by-year basis (the data in the table is net returns, including dividends). In very simplistic terms, the Nikkei 225 has probably produced the most consistently high returns, although it’s also the least investable and based on a poor sampling methodology.

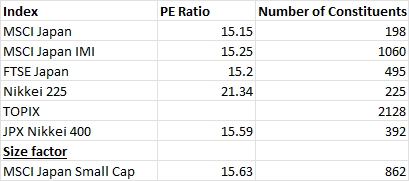

Looking at valuations in the table below, we can see even more variation – and a larger number of constituents for some indices. The broadest index is the Topix index, the cheapest is the FTSE Japan index, followed by the JPX Nikkei 400 index.

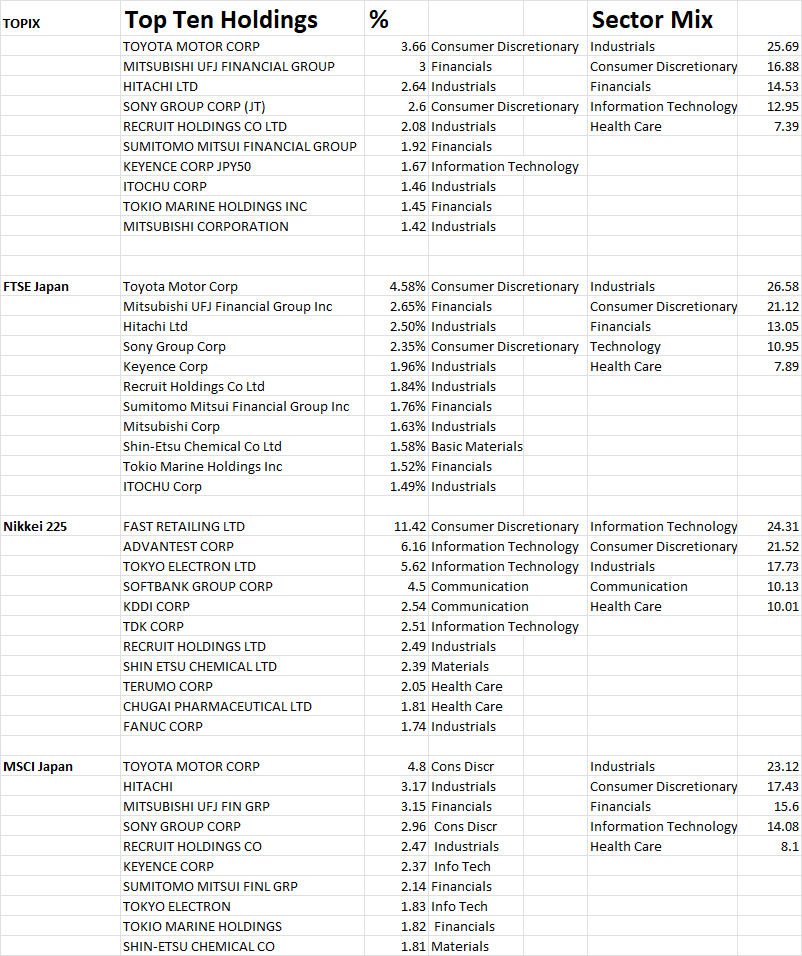

Much of that variation in valuation terms – and performance over the last decade – can be explained by the next table below, which breaks out the sector composition and top stocks within the broad index families: as you’d expect, the Nikkei has a much more concentrated, set of mega large-cap holdings with the top ten stocks, led by Fast Retailing, comprising just under 45% of the value of the index compared to around 25% for the broader, more widely sued indices such as the MSCI Japan index. Information technology as a sector is also much more dominant in the Nikkei 225 index, whereas for the other indices, it is industrials that tend to top the sector weightings at around 25% – the other indices tend to put the IT sector at around 10 to 15% sector weight.

So, looking at the tables above, one might conclude the following: if you buy into the vision of a new Japan, led more by IT firms and with a more concentrated selection of mega large-cap names—and helped by a poorly constructed index—go for the Nikkei 225. If you want a broad index widely used by ETFs, opt for the MSCI Japan or Japan IMI index. If you favour a more value-oriented, fundamental approach, opt for the JPX Nikkei 225 index.

The AI fund: Manchester and London

One of the questions I keep asking myself is why there are so few funds dedicated to artificial intelligence (AI). Now, for sure, there are many, many thematic exchange-traded funds or ETFs that invest solely in AI and robotics stocks, but these are all, by design, passive and thus a little dumb, i.e., there’s no active fund manager making decisions about whether this or that AI stock is a winner.

Over in investment trust land, there are a handful of very successful technology sector funds, not least Polar Capital Technology and Allianz Technology, both of which I rate highly. Ben Rogoff, manager of the Polar Capital fund, is a big fan of all things AI-related, and when you talk to him, he’ll positively talk you under the table about AI.

But by design, again, his fund invests broadly across the tech spectrum. This brings me back to my earlier question: Where’s the specific actively managed AI fund? Dig around a bit, and you might, in fact, discover that there is an AI fund on the London market – it’s just not called that and doesn’t really market itself as one. It is called the Manchester and London Investment Trust and is run by Mark Sheppard, a big shareholder in the fund. On paper, it’s a global equities fund, but in reality, more than 75% of its assets are tied up directly in AI-related firms, and two in particular: Nvidia and Microsoft.

It’s a fund that isn’t without controversy, with some very well-known fund analysts being openly critical, but you have to hand it to the manager, Mark Sheppard – if you are going to take big, bold, concentrated bets, then at least take the right ones. The fund’s big bet is on AI, with Microsoft and Nvidia the biggest holdings by a country mile (over 60% of the portfolio). As you might expect from that big bet, its performance has been outstanding, with year-to-date NAV up 48%, but the shares trade on a chunky 18% discount, which I sense is a bit harsh. The fund has also changed its fee structure, increasing the annual management fee but dumping the performance fee. You could, of course, go and buy Microsoft and Nvidia stock yourself and probably get similar, though not identical, returns to the fund. However, I would say that Sheppard is very much plugged into the whole debate around AI and has been making some interesting side bets on vehicles such as Arista Networks.

Given this backdrop, if you are interested in the whole AI revolution, then I think it is worth listening to what Mark at Manchester and London has to say. A few weeks back I ran an interview for the investment trust website Doceo.tv with Shappard, which can be seen in its longer version HERE. It’s worth highlighting these Q and as below in particular…

Q: Is Nvidia overpriced?

Mark Sheppard: As you can see from the below Chart, Nvidia’s earnings growth (the orange line) has more than kept up with the price (blue line). This means that the valuation (green line) has actually slightly decreased over the last 5 years. To argue Nvidia is overvalued now is to argue it was even more overvalued 5 years ago (at least relative to what the market knew then). Yet from 5 years ago, the returns from Nvidia have been spectacular. Most professional investors understand valuation is a tertiary predictor of future returns (behind 1, Flows 2, Earnings Growth). Besides, we are arguably entering year 3 of the Era of AI and history has taught us that the duration of extraordinary market returns from the introduction of critical general-purpose technologies tends to last a decade. Is there any current evidence that the era of AI will not follow these historic trends?

Q: Can Nvidia keep growing at its current almost exponential pace?

In 2001, Gordon Moore who postulated Moore’s Law, stated he felt that the relationship would break down in a decade because “nothing can grow exponentially forever.” Moore’s Law lives on. But we would agree that Nvidia cannot sustain triple-digit growth rates for too long, and that is already known as Bloomberg consensus estimates have Nvidia revenue growth slowing to 49.8% in Fiscal 2026 and 20.6% in Fiscal 2027.

However, as evidenced by last week’s results (a transitional quarter for Nvidia), that is not currently a function of slowing demand. Nvidia stated that they expect demand to outpace supply well into fiscal 2026 and Huang noted that the suite of AI and robotics opportunities ahead for Nvidia, could amount to multiple trillions of dollars. So, the demand appears to be strong. Execution and supply remain a risk, particularly given the reliance on TSMC for production. Still, if Nvidia can supply anywhere close to the level of demand then the consensus forecasts noted above appear undemanding to us. Just because most investors missed Nvidia does not necessarily mean it will oblige them by failing spectacularly later to save their face.

Q: There’s much talk about AI hitting scaling-up roadblocks. Do you think the AI revolution will slow down?

Last month, Jensen Huang stated, “We’re going to be on some kind of a hyper Moore’s law curve, and I fully hope that we continue to do that. ” This indicates a shift towards new paradigms in computing that extend beyond the conventional model of chip performance improvement from the doubling of transistor numbers to a doubling of computing performance.

Last week Jensen Huang said “My expectation is that, for the foreseeable future, we’re going to be scaling pre-training, post-training, as well as inference” and on Tuesday at Ignite, Satya Nadella stated: “We are seeing the emergence of a new scaling law”.

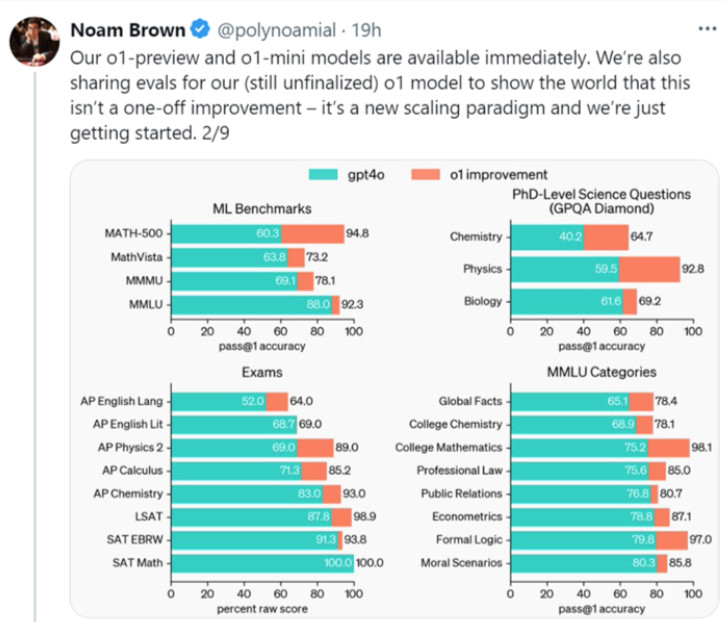

Satya was referring to test-time compute, utilised by models such as OpenAI’s o1 model that undertake extensive reasoning and inference before providing an answer. o1, as a result of these new approaches, showed substantial improvement against Chat GPT 4 in a number of Benchmarks (see below). OpenAi called it a “new scaling paradigm”.

This new scaling could keep foundational model capabilities growing in the short term, but ultimately, the real value of AI will be in the applications it delivers. Foundational models such as GPT are just the starting point; how these are specialised and interconnected with other models to give them the ability to undertake autonomous tasks (Agentic AI) will be the key to realising the enterprise productivity improvements promised by AI. This Agentic era of AI is just beginning, so we expect a lot of improvements from the application level. The key monetiser for AI will be if it can get stuff done, not if it will be your best conversation mate.

Q: What’s your take on Microsoft?

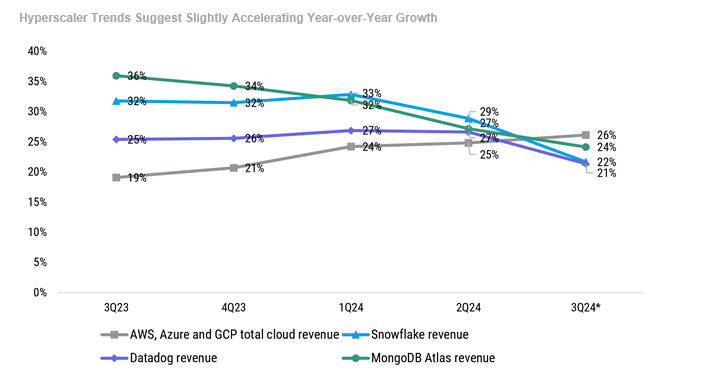

On a metrics basis, Microsoft is an elite stock; on our Bloomberg screens, there are only 6 stocks (non-China) that match Microsoft’s combination of ROIC, ROE, margins and growth (one of these stocks is Nvidia). As we have discussed many times in our newsletters, we see the AI revolution occurring in 4 stages. Stage 1 is the development of the hardware and infrastructure, Stage 2 is moving data to the cloud and organising it so that AI agents can operate on that data. Microsoft, with its Azure cloud business, plays a key role in that second stage and we saw quite clearly in recent quarters an overall acceleration in hyperscaler year-on-year Cloud growth (see chart below).

We have always cautioned that stage 3, which is the monetisation of AI applications, may take longer. However, there is a concern that Microsoft is lagging behind the competition on the applications side, so we believe it is key that Microsoft demonstrates a suite of functional and capable AI agents (not just chatbots) over the next 6 months. Microsoft has publicly talked up the capabilities of their new Copilot agents, but we need to see these deliver meaningful automation in practice. It may be with the emergence of reasoning models, as mentioned above, there is a step change in agent capabilities, and we need to see Microsoft leading this.

Q: What new stocks have found their way into your portfolio, and why?

Our main focus has been on companies that have AI core and central to their business, even if this means the portfolio is highly concentrated due to the leadership of just a few companies in this area. However, a few legacy companies have recently crossed into the threshold of AI enablers. A good example of this is Dell Technologies. Whilst traditionally a desktop PC player, Dell has a rapidly growing AI infrastructure business, offering AI servers (primarily powered by Nvidia GPUs) and storage and networking solutions. This allowed Dell to deliver 9% revenue growth in the latest quarter. Whilst this is lower growth than our other portfolio stocks, Dell appears quite inexpensive on 10.4x EV/EBITDA with a 3.5% FCF yield and a sensible capital return policy.

Q: Outside of the technology sector, what’s drawing your attention at the moment?

Ultimately, we are data-driven, and as noted previously on our screening metrics, few can match the elite levels of Microsoft and Nvidia in terms of growth, ROIC, margin, etc. However, there are a few stocks outside of Information Technology that do reach our high bar, such as Intuitive Surgical. Intuitive Surgical makes robotic surgery systems for minimally invasive surgery. It is one of the more expensive stocks in the portfolio, but its platform offers improved results from non-robotic approaches; it has high technology moats, durable low double-digit revenue growth and, in the long term, is complementary with AI. We have followed and held the stock for several years and it has been a very solid performer. We see a decade of growth still to come for ISRG.

~

David Stevenson

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from David? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for ‘share chat’.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.