Richard Beddard goes through the adjustments RWS made to turn a reported £6.9 million loss into an adjusted £123.8 million profit. He thinks there are generalisations we can apply to many adjustments that make it easier to form a view on their profit.

Oh my word. Translator RWS’ accounts for the year to September 2023 could give the novice reader of financial statements a headache. Did it make a £6.9 million loss as the reported numbers indicate, or a £123.8 million profit, the alternative performance measure the company focuses on?

I think we can form our own view relatively quickly, once we understand the sometimes confounding accounting…

A £6.9 million loss or a £123.8 million profit?

Companies adjust profit to remove costs or gains from the profit calculation to give a more accurate impression of how a business performed.

There are two reasons companies exclude these items. Either no cash flowed out of the business, effectively numbers moved around in the accounting statements but not in its bank account. Or the item is expected to occur infrequently, it is a “one-off” or “non-recurring” item, in which case cash did flow out of the business but for unusual reasons that obscure the “underlying” performance, the profit trend.

The aim should be honourable, but because costs are much more often excluded than gains, it seems managers also use adjustments to dress up the numbers.

When there are big adjustments, it puts investors in a bind. We don’t want irrelevancies occluding our perception of performance, but on the other hand big adjustments could include shenanigans designed to make the performance look better than it really was.

I tend to trust the companies I follow closely, and accept most of their adjustments. However large adjustments require scrutiny.

It is not possible to audit the adjustments themselves, but we can add back any costs we have doubts about to see if the company is performing well enough to justify investment even with them included.

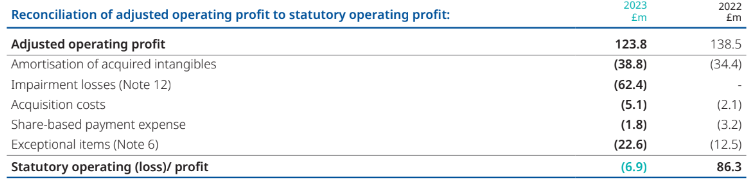

That was my thinking when I examined RWS’ numbers. The translation company reported an operating loss of £6.9m for the year to September 2023, which it inflated to an adjusted operating profit of £123.8m by ignoring certain costs.

Source: RWS annual report page 164, “Alternative Performance Measures”

You might think something very dodgy is going on, but I do not. The bulk of the costs are in the first two adjustments in the list, which are benign. The smaller adjustments are more contentious, so we will see how profitable RWS is if we add them back in.

First, let us dispatch those “benign” adjustments. They both fit into the “non-cash” category.

Irritating impairments

The biggest is impairment losses of £62.4 million. This is a permanent reduction in the value of RWS’ goodwill asset.

In the accounting sense, goodwill exists because accountants cannot always put a number on how much a company’s assets are worth.

It comes into being when a company is acquired and the price the acquirer pays is more than the value of the acquired company’s identifiable assets. This “premium” is a tacit valuation of all the assets accountants could not value.

Assets are expected to generate returns. The impairment means RWS expects to make lower returns from businesses it has acquired in the past than the value of the goodwill carried on the balance sheet.

The value of goodwill is arbitrary, the acquirer’s opinion on the value of another company at a particular point in time. Recalculations of its value can be dramatic and should not, in my opinion, influence our impression of how the business performed in the year.

Indeed if the business is generally run well, management should be increasing its value in ways accountants cannot measure. They will be creating “goodwill”, although the asset cannot be measured or revised upwards unless RWS itself is acquired and the cost of the acquisition reveals it.

Hence RWS’ goodwill asset is almost certainly not representative of all the unidentifiable assets or goodwill in the business, and movements in the asset do more to confound our impressions than inform them.

We can ignore the impairment loss because:

- The adjustment relates to historical costs, no money actually flowed out of the business

- Changes in the value of goodwill can be arbitrary and do not reflect the value the company may be creating

That does not mean the impairment tells us nothing. We should think about whether RWS has overpaid for acquisitions in the past, and might again in the future.

For what it is worth, I think the risk is reduced. RWS is focussing more on knitting together its businesses now, and its appetite for acquisitions is lower.

Inscrutable intangibles*

The next biggest adjustment is the amortisation of £38.8 million of acquired intangible assets. They are amortised, or reduced in value over time like a machine or lorry is depreciated. This is recognised as a cost and deducted from profit.

This does not necessarily mean the company’s intangible assets are worth less. Just as RWS can create “goodwill” but not be able or allowed to measure it, it can create intangible assets and not be allowed to measure them.

For example, RWS’ biggest acquired intangible asset is customer relationships and the amortisation associated with it accounts for most of the adjustment for exceptional items.

Customer relationships are the value of things like contracts and informal relationships, unfilled orders, and customer lists.

Like goodwill, the value of customer relationships is recorded on the balance sheet only when a company buys another company. It is somewhat arbitrary and cannot be revised upwards unless the company acquires another business, but RWS will be winning new business every day.

We arrive at the same place we did with goodwill. We can ignore the amortisation because:

- The adjustment relates to historical costs, no money actually flowed out of the business

- Changes in the value of acquired intangible assets do not reflect the value the company may be creating

Odious one-offs

The footnotes show the remaining costs mostly relate to acquisition costs and business transformation and restructuring.

Acquisition costs are generally fees paid to advisers, like lawyers and brokers and costs relating to raising finance.

Business transformation costs are incurred when companies make people redundant, relocate, and reconfigure or replace IT systems, for example.

It is harder to ignore these costs. They were incurred during the year. And although the company says they are one-offs, RWS has been adjusting out restructuring costs for four years and transformation costs for two years. The longer they go on, the less unusual they seem.

The situation with share based payments is far from ideal at most companies. The cost is calculated using a complex formula and because share-based payments are generally tied to performance targets, they can be highly variable.

But they are real costs, and they are paid routinely, so I think they should be included.

We should consider “one-off” adjustments more carefully, because:

- Money does flow out of the business during the year

- Some “one-offs” happen quite often, even routinely

An opinion on RWS’ profit

Since we cannot be sure ignoring one-off costs improves our understanding of the underlying performance of the business, by adding them back to adjusted profit we can see how significant they are.

In total, the benign adjustments amount to -£29.7 million, which added back to adjusted profit of £123.8 million is £94.1 million.

That is my worst case scenario.

I don’t know how much profit RWS made in the year to September 2023, but I think it is somewhere between £94.1 million and £123.8 million.

On the same basis, in the previous year to September 2022, RWS made somewhere between £120.7 million and £138.5 million.

Worst case or best case, profit fell, and we need to examine why. It does not make RWS a crock though.

Taking SharePad’s number for capital employed (excluding goodwill and intangible assets) of £175.1 million, return on capital in 2023 was 75% using my worst case return of £94.1 million.

SharePad and adjusted profit

For many companies, SharePad includes company adjusted profit and reported profit. As I hope this article has demonstrated, the truth may well be somewhere in between. Often it will be closer to adjusted profit.

It is a good idea to look at both numbers. They give you a best and very worst case scenario. If you are still interested in the business, you can adjust the numbers as you see fit, or maybe decide it is not worth the trouble.

Richard Beddard

Email richard@beddard.net, web https://beddard.net

*It can be difficult to get your head around the accounting of acquired intangible assets. For another good explanation, see the retailer Next’s trading update of 4 January 2024 in SharePad’s news section. The relevant part of the update is: APPENDIX 1: NOTE FOR ANALYSTS ON THE ONGOING TREATMENT OF BRAND AMORTISATION.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.