Companies publish alternative performance measures (APMs) that remove one-off costs and gains from profit to give us a better understanding of how they have performed. Like all financial statistics, though, APMs can be abused. Investors should always check how they are calculated.

Since making profit is the reason for being in business, many Alternative Performance Measures (APMs) are measures of profit or ratios derived from profit like profit margins or return on capital.

Adjusting profit

Investors rely on these ratios to judge the quality of profitable businesses, and hopefully, managers do too. A company’s profit margin tells us what proportion of each £ of revenue is value added by the business, and return on capital tells us how effectively the company turns investment into profit.

Companies that earn high margins and high returns on capital should be more resilient in downturns because they are doing something valuable and profit can fall further before it turns into a loss.

If highly profitable firms are also generating a high proportion of profit in cash flow (they have high cash conversion), they may also have the opportunity to invest the cash they are generating at high rates of return, which means more profit in future.

Although weak cash conversion is not necessarily a sign that there is something wrong with the calculation of profit, it should be a cause for further investigation because there is much less judgement involved in the calculation of cash flow.

The cash flow statement recognises revenue and expenses when money changes hands, whereas in determining profit, accountants change the timing to more accurately reflect the company’s financial position.

Revenue, for example, is recognised when a product or service is delivered, even though payment often comes later. The cost of investment in equipment is spread (depreciated) over as many years as the company is likely to derive benefit from it. Companies provide for costs that they will probably incur in future. Deciding when a good or service is delivered, how long an asset will remain useful, or how much a future liability will cost, is not always straightforward, but these estimates and many others are built into the reported figures.

APMs are adjustments to these estimates, and so they perhaps require even more scrutiny. Companies typically use APMs to deal with income and expenses that are unlikely to recur. They might refer to them as exceptional, non-recurring, or one-off items. By adding back exceptional costs to profit and deducting exceptional gains from it, readers of the annual report can get a better view of how the ‘underlying’ business would have performed had it not been for these exceptional items.

Companies are supposed to give as much emphasis to exceptional income as they do to exceptional costs, but in practice, the majority of exceptional items identified are costs, which boost profit when they are added back.

Since businesses are often judged by their ability to generate more profit and executive remuneration is often linked to profit growth, you can see why this bias might exist.

SharePad calls APMs relating to profit “company adjusted profits”, although there are many different measures of profit and companies do not necessarily do the calculation for all of them so the data is a bit patchy.

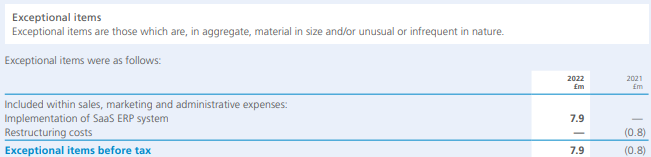

Victrex: exceptional items

For Victrex, a company that makes a specific polymer (plastic) used to make machine components, SharePad quotes a company adjusted operating profit of £96.4 million in the year to January 2022 but quotes a reported operating profit figure of £88.5 million. The difference, £7.9 million, is made of exceptional items.

Exceptional items are detailed in note 3 to the accounts, and mercifully there is only one:

The note goes on to explain that Victrex is implementing a new Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, software that automates and manages business processes usually across a wide range of business functions like accounting, procurement and manufacturing.

Victrex tells us that the programme will cost a further £7 million to £12 million in exceptional costs in the current financial year (to September 2023) and 2024. This is the estimated cost of designing new business processes, configuring the software, changing people’s roles and training them to use the ERP system.

The company says it is treating the cost as exceptional because it is significant (it increased operating profit in 2022 by 9%) and because it is a one-off expense. Once it has implemented the system, it will last indefinitely. It is, according to Victrex, “evergreen”.

In the past, the company did not treat spending on new IT systems as an exceptional cost. The change in policy has been triggered by a decision from an accounting body that spending on cloud-based software should not be capitalised.

This would have allowed Victrex to treat the software as an asset and spread its cost over its useful life:

Presumably, this is because the software is not owned by the business, but rented as a service.

To my mind implementing the new system is an investment, and treating it as one by capitalising it and depreciating it gradually would have been quite an elegant solution, but apparently, this option is no longer available.

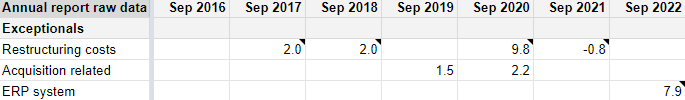

One way we can get a feel for whether exceptional items really are exceptional is to record them over a period of many years, which, as a shareholder in Victrex I have done:

Source: Victrex annual reports

I am not too concerned about the quality of Victrex’s profit because in most years its cash conversion is high, and the exceptional items it has identified are varied, and generally have little impact on profit. But I am a little concerned that they are becoming more frequent and more significant. For years before the period in the table, there were none.

Victrex, once a very profitable and steadily growing business, has been struggling to grow profit for a number of years. When companies’ fortunes are waning, they often report more exceptional costs. This makes sense because they will be trying to turn things around, which requires change. The more costs that are excluded though, the more dependent the adjusted profit figure is on the judgements of the executives and so the opportunity to present a more favourable figure than is justified increase.

Only once has ignoring restructuring costs at Victrex significantly boosted profit and that was in 2020 when it made mostly voluntary redundancies. This was a response to the onset of the pandemic and swingeing reductions in demand in some of Victrex’s big industrial, automotive and aerospace markets, so perhaps it was a one-off.

The reversal in the following year happened because the restructuring cost was less than the company expected.

I am a bit uneasy about the ERP implementation, though. It is justifiable, but it is going to impact adjusted profit for a couple more years, and the company may make other investments in IT that get the same treatment, which would also be justifiable. The adjustments give a better impression of how Victrex has performed relative to the previous year, but they ignore real costs and over time they will mean cumulative profit will be overstated.

For now, I am going along with Victrex’s adjustments, but that does not mean I always will. Should we disagree with exceptional costs, we can add them back in. And should we disagree with any gains a company has included in its profit we can deduct them.

Next time, I will roll my own adjusted profit figure for a company that made questionable adjustments in its most recent annual report.

~

Richard owns shares

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Richard? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.