Market researcher YouGov is known for its predictions, but it may not be the accuracy of those predictions as much as their speed, quantity, and low cost that distinguishes the business.

We have surely all heard of market researcher YouGov. A day barely goes by without the media disseminating the results of its polling.

If an election were held now, Boris Johnson would lose his seat, YouGov says.

We, the British public, think inflation is going to fall to 3.9% in five to ten years’ time.

And according to BrandIndex, a YouGov invention, Amazon and Nike are no longer among the world’s best brands, but Lidl and Shopee, a South East Asian shopping platform, are.

The predictions of bigger rivals seem to me to get less coverage in the media.

Take a look in SharePad and you will see YouGov’s success is reflected in the numbers.

It has achieved double-digit growth in turnover most years since 2014 and stronger profit growth, although there have been a few down years.

Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) and Cash Return on Capital Invested (CROCI), both measures of profitability, have grown strongly over the last five years to an impressive 18% ROCE and a remarkable, and probably anomalous, CROCI of 29% in 2022.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given prodigious cash flows and modest acquisitions over the years, YouGov had net cash on the balance sheet at its last year end.

A big reputation, strong finances and a recently published annual report are all good reasons to identify what makes YouGov special and discern how profitable it really is.

What YouGov does well

From the outset, YouGov has operated differently from other market researchers. The industry is known for stopping people in the streets, or buying lists of people willing to answer questions by telephone or online, so-called panels, sourced from businesses known as panel providers.

YouGov set about creating its own panel by recruiting panellists online and rewarding them with points that convert into benefits or money. This is an ongoing relationship and YouGov has been at it for twenty years.

It routinely polls the panellists, over a million in the UK and over 17 million around the world, and collects much more data, from many more people, than is possible through conventional means.

This Living Data, as the company calls it, has enabled it to build a software platform that clients can interrogate themselves rather than commissioning time-consuming and expensive custom market research projects (although YouGov still earns a diminishing proportion of turnover this way).

YouGov’s latest product demonstrates the power of the data. It launched Surveys Direct in October, which promises self-service results within an hour.

It connects clients directly to the YouGov panel, allowing them to build surveys and get results back from specific audiences like parents in the North East who shop at a particular retailer and young graduates who don’t want to be tracked online.

We can play around with the data ourselves in two free-to-access ‘lite’ versions of two of its commercial data products: Profiles Lite, which profiles the buying habits and attitudes of particular groups, and BrandIndex Lite, which tracks the performance of brands.

This can be amusing as well as enlightening.

Judging by YouGov’s profitability, the investment is more than worth it, because to some degree YouGov’s polling produces cheaper, faster and more accurate results.

More data may help YouGov to get around a big problem in market research: that any sample of the population is an imperfect representation of the whole population.

It feels as though this should produce better predictions, and YouGov is confident enough to publish a pdf document containing some predictions, those of its rivals, and actual outcomes, on its website.

Curiously, the document is underwhelming. YouGov’s predictive record does not look particularly distinguished to me.

Perhaps its competitive advantage lies more in the low cost and high-speed predictions its vast Living Data set can deliver, and the opportunity for it to garner wall-to-wall media coverage.

Whatever the reason, I think YouGov is even more profitable than it looks at first glance.

More profitable than it looks

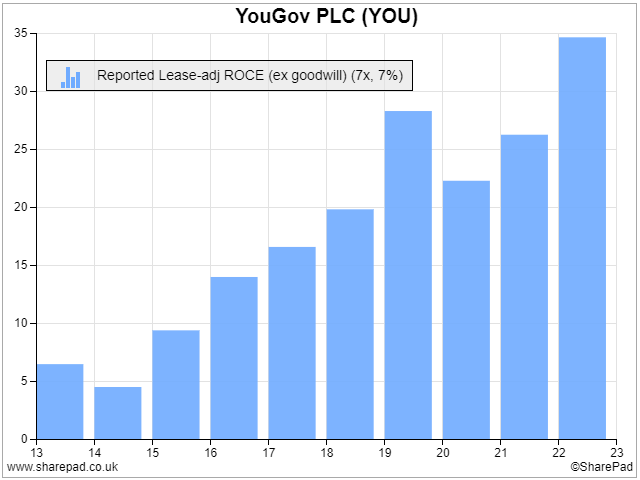

SharePad calculates Return on Capital Employed three ways, by working out profit as a percentage of capital employed, by excluding goodwill from that calculation, or by excluding all intangible assets (including goodwill).

The more we exclude from the calculation, the more profitable the business will look to us for two reasons:

- Capital is the money invested (equity and debt) in assets to operate the business. If we do not count the intangible assets as capital then the capital employed will be lower.

- Profit is derived after deducting the costs of running the business from revenue. One of those costs is the amortisation of intangible assets. If we ignore those costs we increase profit.

Since the return on capital is the profit expressed as a percentage of capital employed, anything that increases profit and decreases capital employed will produce a bigger percentage ROCE.

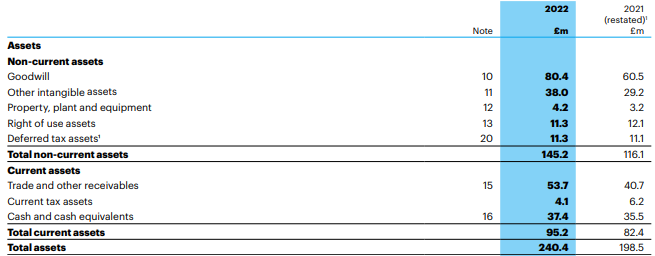

The asset side of YouGov’s balance sheet. Source: YouGov annual report 2022

YouGov’s balance sheet (pictured above) shows goodwill of £80.4 million and other intangible assets of £38 million. That adds up to £118.4 million, almost half of the balance sheet value of YouGov’s total assets.

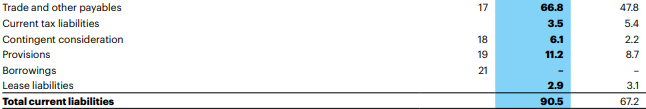

Part of the liability side of YouGov’s balance sheet. Source: YouGov annual report 2022

But capital employed is usually lower than the value of the assets owed by the business, because some of those assets are financed by money in effect loaned interest-free by other entities (it is free capital, so we do not count it).

Most of YouGov’s short-term liabilities are money it owes customers (trade payables), the tax authorities, the previous owners of companies YouGov has acquired (contingent consideration) and people who do work for YouGov (most of the provisions relate to rewards owed to YouGov’s panellists).

Only £2.9 million of YouGov’s £90.5 million liabilities are interest-bearing (they are lease liabilities) so capital employed is total assets of £240.4 million less £87.6 million of free capital, which is £152.8 million.

Our Return on capital employed calculation could have a denominator of £152.8 million (ROCE), £72.4 million (ROCE excluding goodwill of £80.4 million), or £34.4 million (ROCE excluding all intangible assets (£118.4 million).

Which should we choose?

I always exclude goodwill, because it’s a sunk cost. It relates to acquisitions that happened in the past and since it is not an ongoing cost it is not going to impact profitability in future.

Intangible assets are more tricksy. Some intangibles can only be recognised as assets when they are created because of an acquisition (brands and customer lists are the most common) and I treat these the same way as goodwill.

But YouGov deems some of the cost of creating and maintaining its panel and its software platform as investment instead of expensing it straight away. It bundles the cost into assets that sit on the balance sheet and reduce gradually, spreading the cost over a number of years through amortisation.

Conceptually this is the same as investing in a machine or a vehicle and depreciating it.

Unlike acquisitions, YouGov will have to keep spending to maintain these intangible assets, it will have to recruit more panellists and maintain the software, so I do not think we can exclude them.

Since most of YouGov’s intangible assets are internally generated, excluding all intangible assets is a step too far, so ROCE excluding goodwill probably gives us the truest impression of YouGov’s profitability.

By that measure profitability has grown from single-digit levels to 20% plus over the last decade:

Bear in mind too, ROCE excluding goodwill may be an underestimate for two reasons:

- SharePad’s adjusted profit number for YouGov is the same as the reported (statutory) profit, so it does not exclude other exceptional costs like fees relating to acquisitions

- Included in intangible assets are customer lists that were created as a result of acquisitions, which we could also justifiably exclude.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

Got some thoughts on this week’s article from Richard? Share these in the SharePad chat. Login to SharePad – click on the chat icon in the top right – select or search for a specific share.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.