Richard says finding a great business is only the first stage of finding a great investment. The second stage, establishing that what makes a company special is sustainable, is all about fairness.

When buy and hold investors own a share of a business, we expect that share to grow in value as the business proves itself by growing revenue, and ultimately profit.

Self-evidently if the business cannot sustain growth and profitability it is unlikely to be worth more in five, ten, or more years time, and so it will not be a good investment.

Naturally, we try to understand a business’s finances. If it is doing something well, it should be visible in the numbers. Revenue should be growing, returns on capital should be high, or improving, or better still both.

It helps too, to understand how the company makes these returns, how it intends to improve them, and what might get in the way. Analysis of the risks and the strategy that will overcome them can give us confidence in the future.

The company’s financial track record, the risks, its strategy, and, of course, the share price, are four of the five factors I routinely consider (and write about) when I evaluate a share.

The fifth could also fall into the risk category, but it is so important I consider it separately.

Fairness: the crux of sustainability

The fifth factor is fairness: Whether a company treats the people whose lives it affects well. I think it is self-evident that to sustain profitable growth over the long term a company must treat people well.

A business that bullies staff, gouges suppliers, rips off customers, trashes the environment, or syphons off shareholders’ money might get away with it for years, but eventually, the chickens should come home to roost.

People will rebel. They will strike, legislate, prosecute, and walk away from doing business with the company.

In my view, to be sustainable, a business must be profitable enough to reward everybody it deals with fairly, and to be a good long-term investment it must be sustainable.

The problem with things that we believe are self-evident, is that we can feel that we have to explain them very well, or at all.

Today, I hope to put that right with the help of Ensemble Capital, a US wealth manager I have just discovered that uses “Stakeholder Value Analysis” to evaluate businesses for its funds.

Stakeholder value analysis

Ensemble says companies that exploit people are building up off-balance sheet liabilities that will have to pay for one day.

For example, thanks to streaming TV, people were only too happy to ditch cable TV services that had been price gouging for years. But the ratcheting up of the iPhone’s price has been possible not because Apples’ customers are trapped, cheaper Android phones are available, but because they love the product.

When a company’s relationships are win-win, powerful things happen. A fascinating thing about this white paper from Ensemble is that it uses the pandemic period to see which companies have been piling up liabilities and which companies have been accumulating off-balance sheet assets.

Ensemble says fast food companies have been accumulating liabilities. For a long time, they paid staff below minimum wages. Now they are facing above-inflation pay demands as workers attempt to claw back past exploitation at a time of labour shortages.

On the asset side, are companies like Home Depot, the giant American retailer of DIY and building products.

Big-hearted merchants

Home Depot is superficially an American B&Q or Homebase, but listening to Ensemble’s chief investment officer describe the business in this podcast, another UK business comes to mind: Howdens.

Home Base is a retailer supplying a vast product range and Howdens is a trade supplier of fitted kitchens, so the two businesses are superficially quite different.

But both companies had visionary founders that focused on motivating staff to meet the specific needs of a particular customer.

Typically, people go to Home Depot because they have a small job to do in their spare time, or, if they are professionals because they need something quickly to avoid holding up a larger job. It’s very important that Home Depot can supply what they need from stock.

Likewise, tradesmen fitting kitchens cannot afford delays. Howdens gives builders sufficient credit terms so they can complete a job and be paid by their customers before they must pay Howdens.

Like Home Depot, Howdens has focussed on near 100% stock availability. It is one of the many ways these businesses have made themselves indispensable to customers.

Decisions like these are expensive, but it is worth it to gain repeat business and a good reputation, and that repeat business powered the growth of Home Depot and Howdens until they came to dominate their respective geographical markets.

Scale reduces the cost of supplying products, which means high-profit margins and returns on capital. You can see for yourself in SharePad that Home Depot’s profit (EBIT) margin is consistently in the mid-teens, and its return on capital usually exceeds 40%.

Incredibly, since the financial crisis Home Depot has grown revenue 6% a year on average while increasing its profit margins from about 10% to about 15%, without increasing the number of stores it owns. Mostly it has achieved this by courting the business of professional customers and serving them through the infrastructure developed for DIY customers.

Howdens usually achieves profit margins in the high teens, and its return on capital usually exceeds 20%.

Both companies have win-win relationships with their customers. What the pandemic showed was that Home Depot’s relationships with staff and suppliers are also great assets.

Its principal paint supplier turned one of its production lines over to hand sanitiser production to help Home Depot stay open and, incentivised by bonus payments, its unvaccinated but protected staff kept the stores open.

Both companies have coped with the shortages that dogged rivals (Home Depot chartered its own container ship), and have emerged from the pandemic bigger and more profitable than they were before it.

When doing the right thing is not enough.

Sometimes I think wistfully that we could boil investing down to finding a collection of companies that do the right thing, but before we get ahead of ourselves, a cautionary tale.

Trifast makes and sells fasteners: nuts, bolts, rivets and screws that hold together cars, washing machines and numerous other products.

The company treats its staff so well many of them have stayed loyal for decades. Unusually, and charmingly, it highlights their achievements and long service in its annual reports.

Its staff are the point of contact with customers, so they in turn work hard by supplying fasteners to precise specifications to factories around the World when they need them.

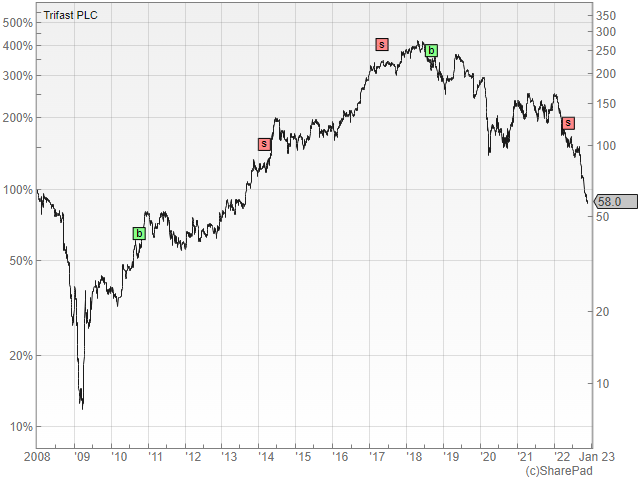

I held Trifast shares for over a decade in the belief that it would progress by doing the right thing, but eventually, I lost faith…

Note: This chart shows trades in the model Share Sleuth portfolio Richard manages for Interactive Investor.

The numbers, ROCE, profit margin and cash conversion, were not consistently good, and as I cast around for reasons why, I settled on scale.

Trifast was trying very hard to expand, principally by buying other fastener manufacturers, but it was still only 1% of a very fragmented global market in which rivals were also trying to put customers first and scale up.

Unlike Home Depot and Howdens, it did not have a unique focus implanted in its strategy by visionary founders, that would make it especially attractive to customers. To my mind, it was sustaining an adequate business, but not a particularly special one.

I thought it was not profitable enough to do right by its staff, customers and suppliers, scale up, and also reward another category of stakeholder, shareholders, sufficiently.

Fairness is not a panacea. Trifast is an ordinary business and being fair to stakeholders is not going to, by itself, turn it into a great one.

As we search for companies to invest in for decades, we need the numbers, the strategy, and a culture of fairness to give us confidence a business is both exceptional and sustainable.

Fairness is a condition of greatness, but not a guarantee of one.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.