Richard was a long-term shareholder in Castings PLC, but he sold his entire holding in 2020. What did he see in the company? Why did he lose confidence after so many years? And what has changed to make him think perhaps it could be a good long-term investment after all?

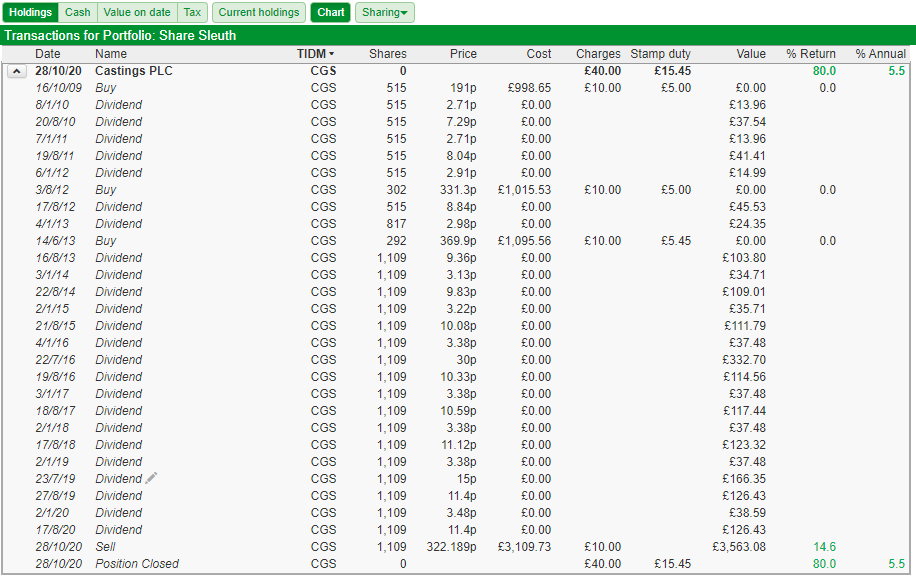

Castings PLC and I have a longish but sadly truncated history. I first bought the shares just after the Great Financial Crisis in October 2009, bought more shares in 2012 and 2013, and sold the entire holding in October 2020:

The chequered trading history of Castings PLC

The trades I am reporting here were made in a virtual portfolio, Share Sleuth (read more here), which I manage using SharePad for the investment platform Interactive Investor.

While no actual money is at stake in the Share Sleuth portfolio, my personal portfolio is a near facsimile of it, differing mainly in size and also the timing of the trades. My personal trades are delayed by at least a week to avoid any conflict of interest.

While I am shy of showing you the underbelly of my own finances, I am quite happy opening up SharePad and showing you Share Sleuth’s guts, which are as I say close to being real trades!

My initial trade was a good one, but my two subsequent trades detracted from it and the end result was a sub-par 80% return, which is 5.5% annualised over the 11-year holding period as calculated by SharePad (and after taking into account broker fees and stamp duty):

So what did I see in Castings? Why did I lose confidence? And why have I regained enough confidence to keep Castings on my watchlist and write about it now.

The good

Castings PLC does what it says on the tin. It casts iron in two foundries at Brownhills in the West Midlands and Dronfield in Derbyshire. Mostly it casts parts for the engine and chassis of heavy trucks, which has grown to contribute about 70% of turnover in recent years.

One thing that often concerns investors is customer concentration. If a company earns a large proportion of turnover from just a few customers, it makes us nervous for two reasons. Should the company lose the customer, it will have a big impact, and that puts the customer in a good position to extract better terms from its supplier.

Castings earns 59% of its turnover from four European manufacturers: Scania, Volvo, Daimler and DAF, but this may be one of those weaknesses that turns out to be a strength.

Heavy goods vehicle platforms last a decade or more in production and once a part has been designed into one it would be expensive for a manufacturer to source it from another supplier. Castings has enjoyed good relations with its customers for many decades.

The company’s strategy is to source more work from its existing customers and their suppliers, like brake manufacturers.

It has specialised in the rapid prototyping and highly automated production of large numbers of relatively low volume parts, something few of its competitors want to get involved in because automation is expensive and more profitably applied to large volume production.

The heavy investment required depresses cashflow, but in every other respect Castings has gloriously straightforward accounts. It has no debt, no operating leases, and though it has a defined benefit pension obligation the assets of the pension scheme are usually greater than the liabilities. The company expects to wind up the scheme in 2022.

In other words, Castings was a profitable, prudently run business when I bought the shares, and its strategy seemed coherent.

The bad

What I have said about the company’s balance sheet and strategy is still true today, but the proximate reason for my loss of confidence was that Castings’ performance had deteriorated.

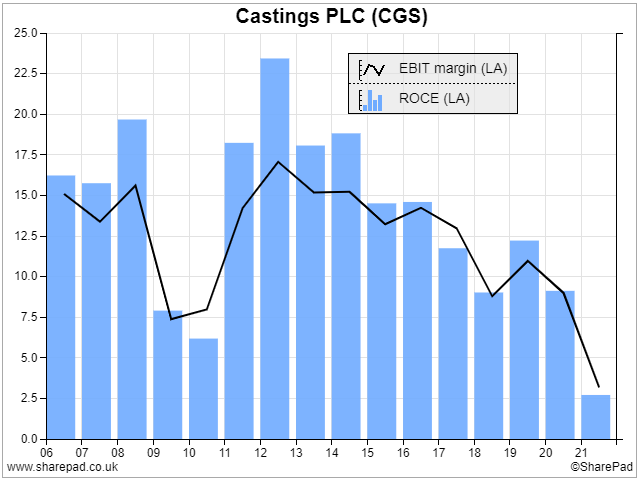

After the Great Financial Crisis, Castings’ profitability returned to 15% or more, the healthy level it had achieved in the year to March 2008 and before. But in 2020 and 2018, Return on Capital Employed fell below 10%.

Obviously I did not know what 2021’s result would be when I sold up in October 2020, but it was a fair bet it would be poor due to the closure of factories during the pandemic, destocking and higher raw material costs (which the company will recover over time through price rises). Volumes are recovering and so I think an ROCE of 2.5% is anomalous.

Throughout the second half of the 2010’s, the foundries performed well. But the third part of the business, CNC Speedwell, started losing money, and that dragged down Castings’ profitability.

CNC Speedwell is Castings’ machine shop. After parts are cast they are finished by computer-controlled milling machines and lathes. Castings acquired CNC Speedwell in 1996 at the behest of Scania because involving two companies in the manufacture of a single part was too much hassle. If there was a defect, the machine shop would blame the foundry and vice-versa.

In its reports, Castings never adequately explained what went wrong at CNC Speedwell. Pressed at an AGM the directors said that in a highly optimised environment like a machine shop it does not take much to knock processes out of kilter and once one job is delayed, it has a knock-on effect on the next one.

Very quickly a company can find itself operating extra shifts and expediting deliveries, all at extra cost, so as not to disappoint very important customers.

The absence of information, though, made me wonder. Perhaps Castings was not achieving enough sales growth from its existing customers and it had sought new and more troublesome business. Or perhaps it was experimenting with new materials.

The materials question arose because of a looming challenge: electrification. It seems highly likely that even heavy vehicles will one day be battery powered. That day is further off than it is for cars because of the distances trucks travel and the weight of their loads.

Electric vehicle engines are simpler than internal combustion engines and employ much more aluminium, putting a question mark over a significant chunk of Castings’ turnover. The problem was, I did not know how much turnover was under threat, or what Castings planned to do about it, but I had learned from a conversation with the company’s chairman that it might experiment with aluminium.

A smaller risk, and to my mind, one that I could probably bear, is the long-term impact of Brexit. Volvo and Scania are Swedish, Daimler is German, and DAF is Dutch, so should the terms of trade with the EU deteriorate, perhaps it would trigger these companies to change suppliers. Comfort comes from the fact that Turkey, a non-EU country, has long been a supplier of volume parts to European truck manufacturers.

All companies face challenges, but it was the spartan communication about what went wrong at CNC Speedwell and the electrification elephant in the room that disconcerted me.

And that is what has changed, at least as far as electrification is concerned. The company broke cover (to my mind) last month when it hosted a private investor webinar.

The facts

To summarise, Castings’ medium term future on heavy truck platforms seems assured. It will supply more of the new engines its biggest customer Scania is currently introducing. These engines will also be supplied to MAN, which like Scania is owned by VW. It may also be supplied to Navistar, a US truck company recently taken over by VW.

Castings will also supply a new manifold system to Volvo, its second-biggest customer. Its third-biggest customer is a relatively new one, Daimler, the source of 1% of turnover in 2011 but 10% in recent years. This growth is particularly impressive because historically German manufacturers have preferred German foundries, although Daimler’s US truck arm, Detroit Diesel, has been a strong source of growth.

Longer term, in five to fifteen years, Castings anticipates some “technology substitution” based on the published plans of its customers. Scania expects 50% of commercial vehicle output to be powered by batteries by 2030, although some of this will be light commercial vehicles. This target anticipates improvements in battery technology and the charging network.

Volvo and Daimler are working together on hydrogen fuel cell heavy trucks. Both expect fossil fuel-free fleets by 2040 also based on technology and infrastructure that is a long way from full development.

Some parts of the business are not thought to be under threat. Chassis, which are responsible for about 35% of group turnover, are still likely to be made from iron. Over 20% of revenue is derived from other industries.

The threat is to Castings’ engine business, which is 35% to 40% of turnover, over the next ten to fifteen or so years.

But, in the Q&A at the end of the presentation, the company says that it still expects to supply some engine parts, particularly brackets, to electric vehicles, reducing the impact to 10% to 15% of turnover. It also anticipates weaker competitors will leave the market, allowing Castings to pick up more heavy truck business.

Beyond that it is looking to partner with or acquire a business with capabilities in aluminium, which would enable it to supply more of the engine.

An acquisition would be a bold step. Castings PLC has not made one since CNC Speedwell in 1996, the last time Castings made a dramatic shift in strategy in response to customers.

As CNC Speedwell has been the main cause of Castings’ decline in profitability in recent years, it raises doubts about the company’s ability to adapt successfully when change is thrust upon it.

On the other hand, Castings PLC has remained profitable, derives a bigger proportion of its turnover from its main customers as prescribed by its strategy, and but for the pandemic CNC Speedwell would have been profitable again by now.

This potential investor feels much more comfortable now he understands more about the scale of the challenge, and how the company plans to address it, and feels somewhat shabby for selling the shares.

~

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

Do you have any trades you’ve later come to regret? We’d love to hear from you in the comments section below

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.

Hi Richard, another fantastically eloquent explanation of how a particular company works.

Personally, this sort of impending major disruption to a company’s core business makes me very wary. I own one company (Senior) that manufactures heavy truck components, mostly metal bellows, tubes and pipes for exhausts and heating/cooling systems. Trucks are going to be disrupted as much as cars within a decade or so, so it’s very important for investors to understand and management to explain how the company is going to adapt to and preferably benefit from this transition.

For Senior the argument is that liquid and gas flexible tubing components will still be needed in fuel cell and battery trucks, and perhaps even more so given how critical thermal management is for improving battery lifespan.

For now I’m buying that argument, but as you point it’s worth thinking about these things, even if they’re ten or more years down the line.

John

Thanks John. I really appreciate being called eloquent!

Yes it’s a headache all right and its a perfectly legitimate thing to cast companies faced by disruption into the ‘too hard’ pile. I don’t know Senior, but in the case of Castings that is essentially what I did because the company was not giving me much to go on.

However, Castings is extremely well managed (despite events at CNC Speedwell) and as you know such confidence is hard won! The question on my mind is which is the more signficant challenge to Castings’ customers – finding new suppliers or the supplier changing material. Based on the Castings move into machinery I think it might be the former.

Thinking about shares I have profited from, I can only think of one that has pivoted and served me very handsomely and that is Tristel the hospital disinfectant company. That pivot was much greater though – the entire business model had to change.

machining, not machinery!

Back in the day I visited Castings in a professional role. I was impressed by their concentration on the basic skill set. No doubtful expenditure on computer modelling. Casting is an art form not a science. It is difficult to translate between casting different metals. Casting aluminium is different from casting steel (which is something of a nightmare) or iron. Those who have tried to transition between these different metal worlds include a few hi-profile disasters.

In essence they were consummate professionals in a world populated by dozens of junk companies. I wasn’t surprised that big industry beat a path to their door. The family story worried me a little – on the ‘clogs to clogs in two generations’ basis.

I sold my shares on the machining debacle. Machining these days requires no skill and the capital expenditure demands high and continuous throughput – a classic service industry. To me it was clear evidence that they been seduced by an opinionated idiot.

They have not stuck to their ‘last’ and there is no turning back. I will not be returning to share ownership and mourn the passing of yet another jewel in the crown of manufacturing industry.

apad

Thanks Adrian, and good to hear from you again. As always, I will take what you say very seriously. If you have time to explain I would be interested to hear about the family story as I am not aware. I have heard this before that you cannot add value through machining (except perhaps as intended vertical integration with casting makes the whole manufacturing process more efficient).

All the best,

Richard.

Richard, was having a look at Castings’ presentation on its latest half year results https://youtu.be/w__MCctX1Cg and read your recent commentary on why you might have a second look at the company.

There is nothing I can really add to your very good analysis of where the company is, and where it is going. The management does not hide the challenge that it faces as heavy duty truck manufacturers, accounting for 70% of its business, are forced by climate change obligations to find an alternative to diesel. The CEO says it will still be a “very good business” for the next 8-10 years, but the eventual phasing out of diesel engines could lead to a 35-40% drop in its business.

It has been talking for a while about diversifying into aluminium casting, which is much more important for electric vehicles. It tried unsuccessfully to buy a “distressed” aluminium foundry, and is talking to a potential customer to see if it will back CGS setting up its own aluminium foundry. But as mentioned by another comment on your piece, aluminium casting is a different sort of business from steel and iron casting. In addition, the past acquisition of CNC Speedwell, CGS’s marginally profitable machining business, suggests that corporate M&A is not one of the company’s strong points.

The combination of the long-term move away from diesel challenge, combined with the short-term supply problems causing OEM’s to cut back their planned orders, perhaps explains why CGS shares have been going nowhere for years.

The contrast between Goodwin, another of your favourites, and Castings is stark. Both are in different ends of the foundry business, but GDWN has a market cap of £270m, more than twice its sales, whilst the bigger CGS has a market cap of roughly £156m which is only £10m more than this year’s forecast sales. CGS has £40m of cash, a progressive dividend policy, and its shares yield 4.2% compared with GDWN’s 2.8% yield. It is also valued at close to tangible book value.

On paper the business outlook for GDWN looks more exciting. It has a growing refractory business balancing a traditional foundry business which is fast replacing its dependence on the oil industry with a growing nuclear business.

However, there are a couple of points in Castings’ favour. It has a rock solid balance sheet, and its two biggest shareholders – Ruffer and Aberforth – have been slowly increasing their stakes over the last couple of years. In addition, Brian Cooke, the chairman, continues to add to his 4.55% stake buying small parcels of shares on four separate occasions over the last year.

Mr Cooke has been with the business for over 60 years and is now over 80, (although the company no longer discloses the ages of its executives in its annual report). The rest of the board and management do not have sizeable stakes in the business which raises the question of what will happen to the company when Mr Cooke eventually retires.

Like Ruffer and Aberforth I am tempted to tuck away a few shares in CGS on the off-chance that something might happen to reignite its share price over the next five years, whilst collecting a reasonably safe yield of over 4% on my investment.