James Halstead makes vinyl flooring, the kind we see in hospital corridors, GP surgeries, clinics, schools, offices, laboratories, prisons, factories, shops, trains and boats around the world.

James Halstead’s biggest brand is Polyflor. The company’s social media accounts are a good way to get a feel for the product and you can take the Commercial Visualiser for a spin too. Source: Twitter.

Vinyl is a product of two of the most abundant chemicals on the planet. Plenty of companies make it but it would appear that there is something special about James Halstead.

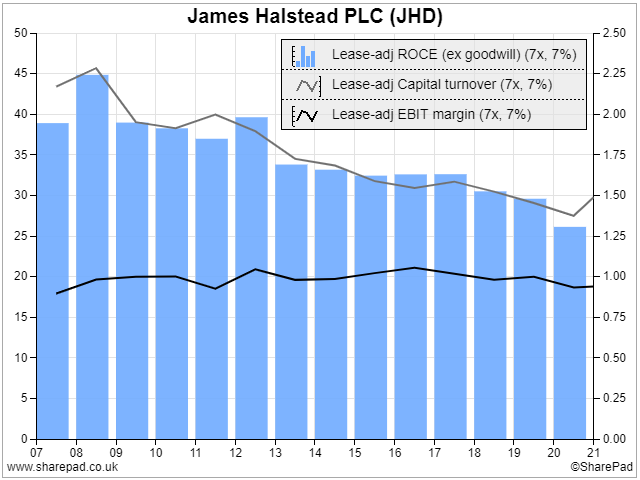

It has earned extraordinary, albeit declining, Returns on Capital Employed (ROCE) for many years:

Return on capital employed (blue bars) is the product of two ratios: profit/turnover (profit margin) and turnover/capital employed. James Halstead has sustained high profit margins (thick black line) but it is deploying more capital to make sales (thin grey line).

The steeper decline in return on capital in 2020 is due to the nationwide lockdown earlier this year, which coincided with the last three and-a-bit months of James Halstead’s financial year. It reported a 9% decline in pre-tax profit.

I have two theories that may explain the more gentle decline in ROCE in previous years. The first is that the industry is more competitive than it was. The second is that the company has invested in more capital than it strictly needed to.

Before we address these theories, we need to establish why it is so profitable.

How does James Halstead make so much money?

James Halstead does not dwell on strategy in its annual report, it believes competitors scour the document like it scours theirs.

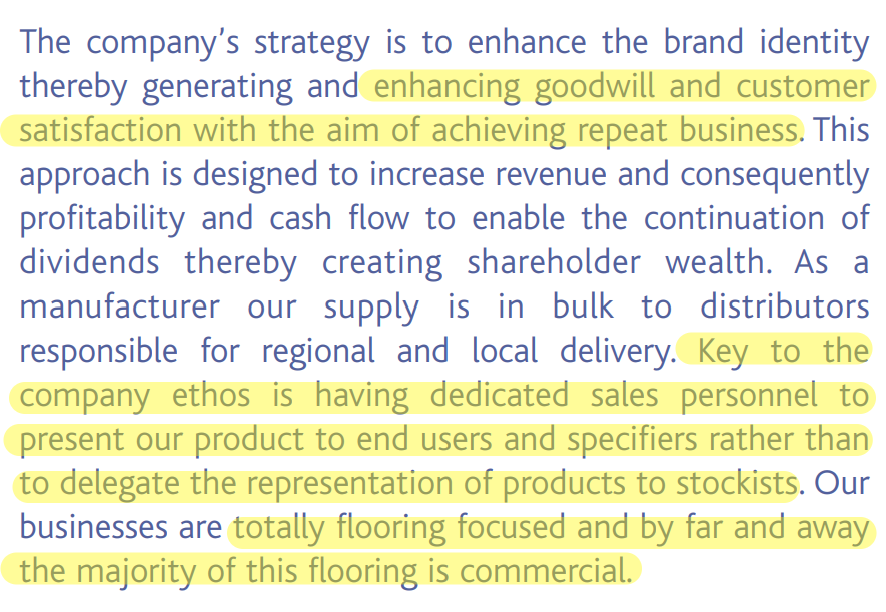

Maybe, though, what James Halstead does well is simple, but not easy. This is what it says about strategy in the annual report. Blink, and you may miss it:

Source: James Halstead annual report 2020.

Two things stand out in this paragraph. The first is James Halstead’s determination to be part of the sales process and not leave it entirely to the distributors who stock the flooring, and fulfill orders.

This is a strategy it shares with other highly profitable suppliers to construction and refurbishment projects, like lighting system manufacturer FW Thorpe.

By working directly with architects, consultants and end customers, it can help them choose the right product. By bringing the sale to the distributor it can sometimes claim a greater share of the profit.

The other thing that stands out is James Halstead is a specialist in commercial vinyl flooring. Specialists, who focus on doing one thing well, often outperform generalists.

The directors believe the simplicity of the organisation helps it compete with much bigger rivals. There are not many layers of management between the directors and the people making and selling vinyl flooring at James Halstead.

While competition is no-doubt intense in vinyl flooring, it is not necessarily dog-eat-dog. James Halstead thanked two competitors, Altro Group and Amtico International, for help with PPE during lockdown, when James Halstead kept its production line going to supply hospitals in the UK and around the World.

Growth conundrum

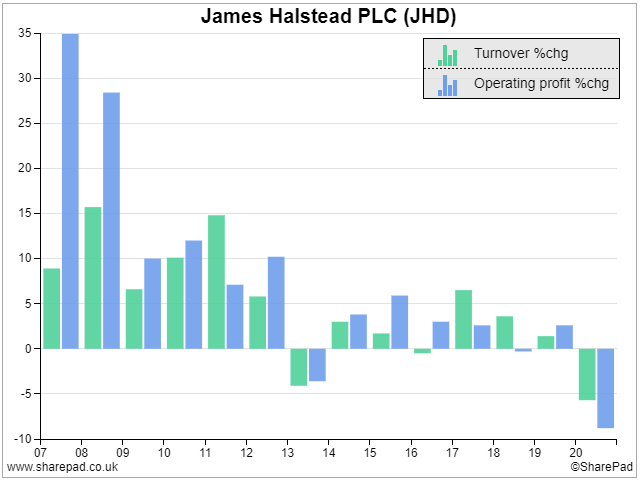

Despite James Halstead’s impressive returns, for most of the last decade the company has grown pretty slowly:

Annual percentage change in revenue and operating profit. For much of the naughties, James Halstead grew rapidly. Since then it has plodded.

The hope with highly profitable firms, is that they can use their competitive advantages to earn even more profit, financing investment from their prodigious returns.

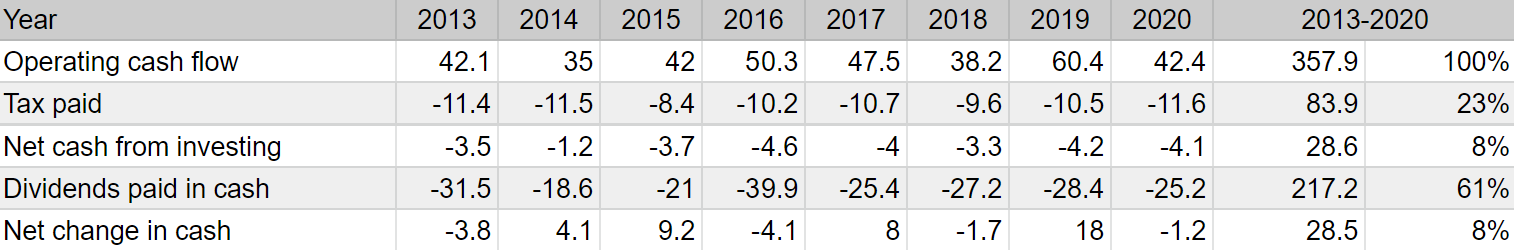

The company tells me it has a simple rule: one third of cash for the tax man one third for the shareholders and one third re-investment. So let us have a look at what James Halstead has done with its cash by exporting the cash flow statement from SharePad and totting up the rows in a spreadsheet for the period of slower growth from 2013 to 2020:

Major elements of James Halstead’s free cash flow 2013-2020. Data source: SharePad. In the cash flow statement tax, investments, and dividends are deducted from operating cash flow, which is why they are negative. I have expressed the cumulative totals as positive numbers to calculate the percentage of operating cash flow used. A cumulative 8% of operating cash flow was unused, and at the year-end formed part of James Halstead’s cash surplus.

The table shows what James Halstead spent its operating cash flow on during the last eight years. Corporation tax used up 23% of operating cash flow. Net capital expenditure is capital expenditure less the sale of fixed assets, and this investment only used up 8% of operating cashflow. Shareholders received a whopping 61% of operating cashflow in dividends, though.

Muddying the picture somewhat is the growth in James Halstead’s cash surplus amounting to 8% of operating cash flow, which has yet to be used. Conceivably in the future some of it might be invested, or returned to shareholders.

Lack of will?

It looks as though James Halstead is prioritising dividends over investment but the truth is more complicated. Investment can mean many things. Applied to the cash flow statement it basically means capital expenditure (buying buildings and equipment) and acquisitions (buying companies).

James Halstead may well mean it in the wider sense of the word – any spending, be it on product development, training, or building the brand that is likely to earn the company more profit in the future. These costs come out of operating cash flow and so James Halstead is probably investing more, and paying more tax.

The company says it is increasing its sales resource in Asian markets, including Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, so that is one potential avenue for growth.

It also concludes from home-makeover shows in which Polyflor vinyl has featured that it can gain market share in the residential market, though it says its focus remains firmly on commercial sales.

Or opportunity?

However we define the word though, James Halstead is probably not investing a third of its cash flow. That is not because it is prioritising the dividend, after all it could have paid an even bigger dividend if it wanted to from the cash it is accumulating. It does not need more machinery.

The company tells me it is only running at 50% capacity having invested heavily in a new factory in Teeside in 2010 (you can see the blip in capital expenditure in the cash flow statements from around that period).

If the reason for the lack of growth is not lack of will, then it may be lack of opportunity. Economic uncertainty has tightened corporate budgets and constrained government spending around the world. This may explain reports of over-capacity in the industry.

The future is unknowable, and I am not able to speculate intelligently on how long Covid-19 will be with us or the extent or impact of the recession we are experiencing.

However investors have largely kept faith with James Halstead, and it is pretty clear why. The business performs well even in difficult times, it has £67m in cash on the balance sheet and spare capacity should rivals go out of business or economies pick up.

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.