The demise of Thomas Cook impacted the whole package tour industry including London listed Online Travel Agent, On The Beach. Whether you trust the accounting regulations or On The Beach’s adjustments makes a big difference to the company’s profitability in 2019. Richard unravels the exceptional items.

It’s January, The BBC is screening Death in Paradise, and our thoughts may have turned to booking summer holidays. Coincidentally, On The Beach, the UK’s number one Online Travel Agent (OTA), has just published its annual report.

On The Beach is one of the companies vying with Jet2holidays and TUI to fill the void left by Thomas Cook, which went bust in 2019. Formerly Thomas Cook was the UK’s number three package tour operator.

To give you an idea of the competitive landscape, these are the top seven UK travel companies by number of passengers they are licensed to carry on package holidays under the ATOL protection scheme:

| Licence Holder | Passengers |

| TUI UK | 5,555,145 |

| Jet2holidays | 3,915,000 |

| On the Beach | 1,646,800 |

| We Love Holidays | 1,374,812 |

| British Airways Holidays | 1,010,148 |

| Expedia | 874,208 |

| easyJet | 793,874 |

| Source: Civil Aviation Authorit | |

Apart from the disappearance of the inventor of package holidays, Thomas Cook, which was founded in the nineteenth century, it’s notable that three of the top four travel companies on the list were founded in the twenty-first century: On The Beach in 2004, Jet2holidays in 2007, and We Love Holidays in 2012. TUI, which is somewhat old school, still heads the list though.

When is a package holiday not a Real Package Holiday™

Like third placed On The Beach, fourth placed We Love Holidays is a dynamic packager (it trades as loveholidays). Hitherto these companies haven’t operated planes. They are websites and call centres that use algorithms to match holidaymakers with scheduled flights, often on budget airlines, and rooms sold by bedbanks (wholesalers) or contracted directly from hotels and resorts.

The distinction with Real Package Holidays™ is so significant, Jet2holidays has trademarked the phrase. Companies selling Real Package Holidays™ have more control of the product, they operate planes, have strong relationships with hotels and employ reps to help holidaymakers. They control when they fly, and what level of service they give. Companies selling dynamic packages offer choice and low prices. Clearly there is more than one way to crack an egg, as the fastest growing travel companies come from both sides of the divide.

Also notable is seventh placed easyJet, not because of what it has achieved but what it might achieve having invested heavily in easyJet holidays, which launched in November and further blurs the boundaries. Like Real Package Holidays™, easyJet holidays flies holidaymakers on its own planes, but it doesn’t have reps on hand to help them. Instead they are serviced by an app or by ‘phone. No Resort Flight Check-In®, like Jet2 then?

When is a profit not a real profit?

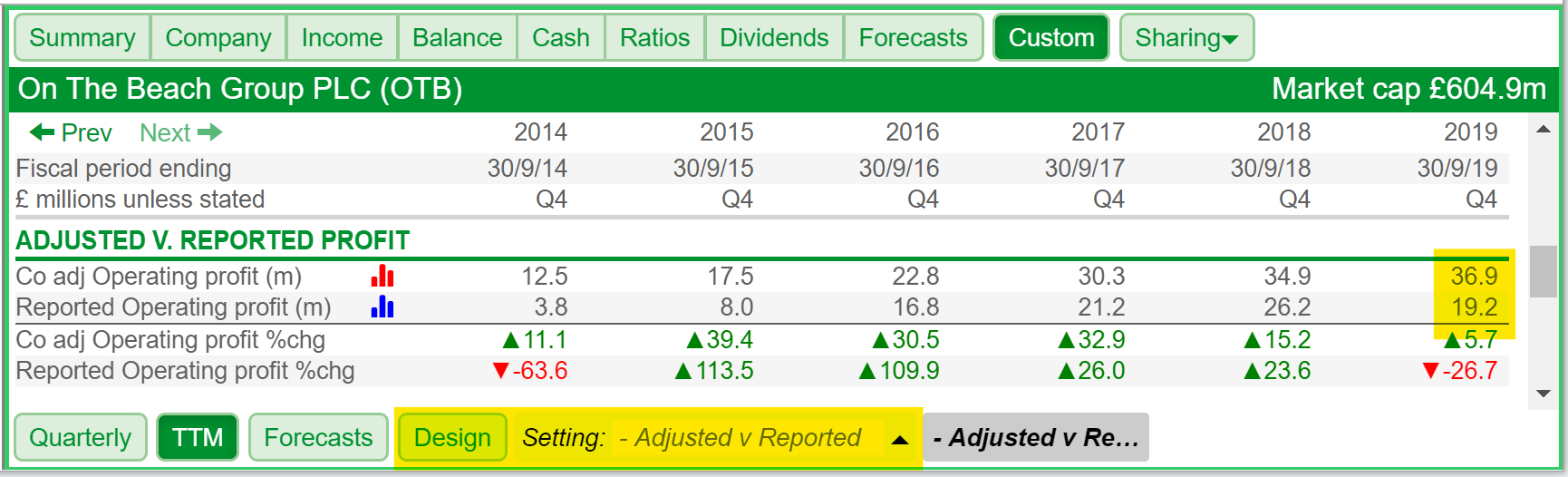

The difference between Real Package Holidays™ and dynamic packages was written in On The Beach’s profit and loss account for the year to September 2019, which we can see in the difference between reported profit and company adjusted profit. I have laid out the stats in a custom SharePad table below:

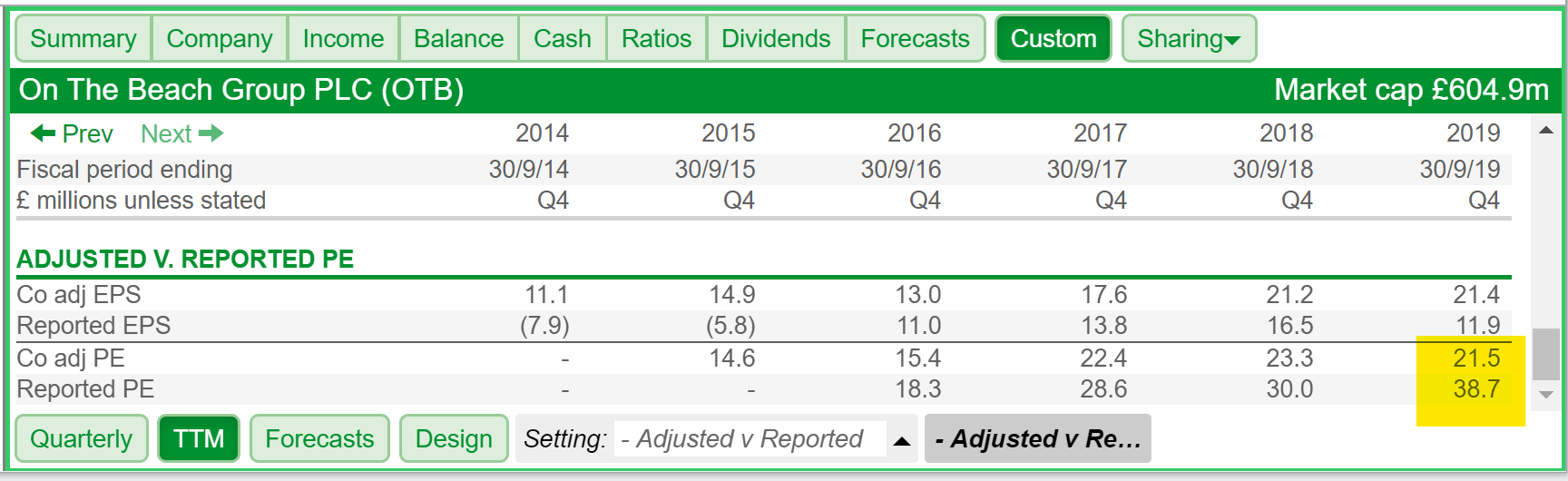

[You can create your own custom tables by clicking Design (highlighted in yellow above) in SharePad’s Custom tab. If you have lots of custom tables you can also organise them into different pages or Settings. This custom table is in my Adjusted v Reported setting, as is the table below showing the On The Beach’s PE ratio.]

Reported profit figures are derived from a company’s application of accounting regulations, but companies often seek to adjust the figures to present their view of the ‘underlying’ performance of the company were it not for certain one-off events that impacted profit.

In each of the last five years, On The Beach’s company adjusted operating profit has exceeded reported operating profit by some margin. According to SharePad, company adjusted profit was £36.9m in 2019, up 5.7% on the previous year’s figure. Reported profit was £19.2m though, down 26.7% on 2018.

Since many of the ratios investors use to judge the performance of companies are derived from profit, we need to take a view on whether On The Beach’s adjustments are justified. The differences are significant. Depending on which measure you use, On The Beach’s PE ratio is 21.5 or 38.7 (at a share price of 460p).

To investigate, we need to turn to the annual report. The exceptional items are listed in note 7d on page 117, but the company provides more detail on the exceptional items arising from the collapse of Thomas Cook (TCG) on pages 7 and 8. Here I have taken these exceptional items, and added them back to reported operating profit to derive company adjusted operating profit:

| Reported operating profit (£m) | 19.2 |

| Impact of TCG on revenue | 7.1 |

| Exceptional TCG costs | 0.6 |

| Amortisation of acquired intangible assets | 5.5 |

| Restructuring costs | 0.8 |

| Share based payments | 0.7 |

| Exceptional property costs | 0.3 |

| Other | 0.2 |

| Adjusted operating profit (£m) | 34.4 |

On The Beach adjusts its profit figures in a number of ways, and this calculation is £2.5m less than the figure used by SharePad for reasons too arcane to go into here. Let’s just say there is more than one adjusted profit figure in On The Beach’s annual report! Even so, we can see On The Beach has excluded substantial ‘costs’ to show us how well it really thinks it did. I have colour coded them to show how accepting I am of the adjustments.

It’s reasonable for companies to adjust-out the cost of amortising acquired intangibles (highlighted in green) for reasons I explained in an article on Bloomsbury Publishing (see the section on “taking out the sunk costs”), but I disapprove of companies that adjust-out share based payments (highlighted in red), which are a routine way of paying executives and ultimately a cost borne by shareholders.

The items highlighted in orange are often justifiable, but they are something of a pandora’s box. We only have a company’s word for it that it has not overstated, say, the cost of restructuring, when the prevalence and extent of performance related pay means executives have a powerful incentive to maximise profit by any means they can. One reason so many people were ignorant of the risks building up in Thomas Cook, was that they believed the company’s heavily adjusted figures.

Thomas Cook features in On The Beach’s adjustments because On The Beach had booked customers on Thomas Cook flights. The biggest exceptional item, £7.1m, is not technically a cost, but the revenue On The Beach lost by refunding customers whose holidays were cancelled or rearranged at greater cost. At the year-end On The Beach expected to get back most of the money it paid for Thomas Cook flights from the credit cards it used to pay for them, so the £7.1m is lost profit – what it would have earned from customers if they had been able to fly with Thomas Cook. On The Beach explains that had Thomas Cook flights not been available when it made the bookings, these passengers would have booked through On The Beach with another airline. This may be a reasonable assumption, but I don’t think we can be sure pricing or scheduling would have been the same. Perhaps some customers would not have found the holidays they wanted.

When is a no risk business model risky?

Apart from raising questions about how much profit On The Beach actually earned, the episode also makes me question the no risk aspect of the “no risk, lightweight business model” On The Beach operates. OTAs don’t bear the risk of owning planes and hotels, which are expensive to buy and maintain and result in losses when they are not adequately utilised. But a glance at the company’s key risks in the annual report reveals a number of risks pertaining to suppliers, including a long-running legal battle between OTAs including On the Beach and Ryanair. Ryanair is seeking to prevent them from booking flights by claiming OTAs infringe its intellectual property rights by using its schedules and prices.

Neither is the demise of Thomas Cook a first. It occurred only a couple of years after Monarch went bust. On The Beach lost money then, and it would lose again if another supplier went bust. Meanwhile, the loss of capacity is forcing up prices and consequently On The Beach’s costs, and On The Beach shares in the reputational damage of its failed suppliers.

Finally, On the Beach is becoming more like a package tour operator. For example, it is contracting more hotels directly (70% in 2019), which improves customer satisfaction and will enable it to take some of the capacity that has been released by Thomas Cook, and it is contracting with airlines for seat allocations on popular routes. While it seeks to build flexibility into the contracts, they must expose On The Beach to some of the risk of conventional package tour operations.

Even though I believe airlines and OTAs will come to terms and I would go along with most of On The Beach’s adjustments meaning its PE is probably closer to 21.5 than 38.7, the business model is in flux and I am in no hurry to risk an investment.

Richard Beddard

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.