A wise man once advised investors to stick to their circle of competence. Richard uses SharePad to keep his eye on the prize, and it leads him to Bloomsbury Publishing…

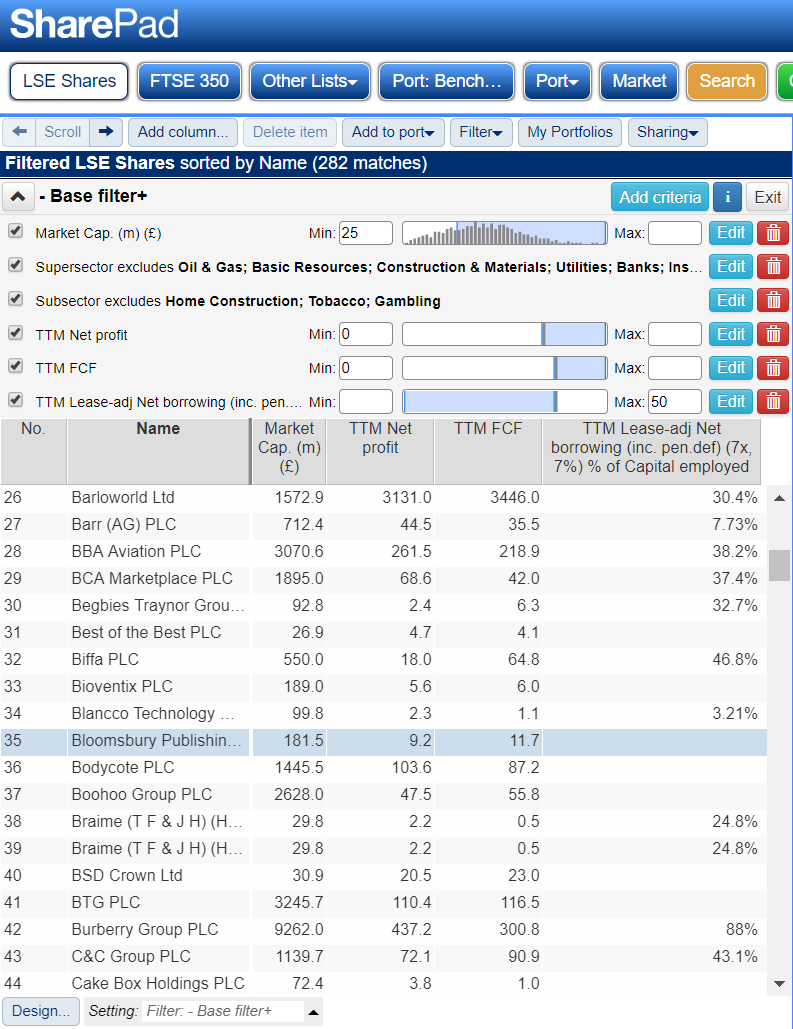

My base filter in SharePad currently returns a total of 596 shares listed in London. It does not do anything clever. It just excludes the very smallest companies, those in capricious industries that I am not competent to investigate, and avaricious ones that may do more harm than good.

Cutting through the dross

It is surprising how adding the laxest of criteria can dramatically reduce the number of shares a filter brings back. The bare minimum I look for in a business is that it is profitable in accounting and cash terms and that it is not hamstrung by debt.

Adding those criteria individually, returns the following tallies:

- Net profit > £0: 428 matches

- Free cash flow > £0: 398 matches

- Net borrowings as a percentage of capital employed* < 50%: 470 matches

Nearly 30% of the companies in the more respectable stockmarket nooks and crannies are making a loss on an accounting basis, over 30% of them are making a loss on a cash basis, and more than 20% of them are mostly funded by outside money.

Apply all of these ratios simultaneously and 282 shares pass. Three hundred and fourteen, more than 50%, do not meet these basic criteria.

They are not all losers. Some loss-making businesses triumph, but separating the potential winners from the legion of losers in this group of startups, turnarounds and serial failures requires different skills to analysing companies that already earn a return, when all we need to do is determine how likely they are to sustain or improve it. To me, these established businesses are “normal” companies. They can be appraised with the standard tools of the trade: PE ratios, profit margins, and so on.

It was Warren Buffett who advised investors to stick to their circle of competence, a flowery way of saying “buy what you know”, and shares returned by the filter based on the criteria above, or similar, are most likely to be in my circle of competence:

There is always a temptation to narrow down the pool of shares from which to fish but I try not to because there is more to appraising a business than the numbers. From this point on I want to consider the company in the round: how it makes money, whether it is likely to make more, and what could stop it.

Phase two is to pick a share, and follow our own noses, checking the story we are developing about the firm against the numbers in SharePad.

Picking a company from a large list

This is where randomness, serendipity and our own personal quirks come into play. I have not been following Bloomsbury, but still it is surprising that I have not heard a squeak about it even in passing for the best part of a decade. The investors I follow on Twitter are not tweeting about it, and I cannot remember reading about it in the business pages of the Times. If its profile is lower than it once was, that is a good sign because the shares may be undervalued.

Years ago Bloomsbury was a high growth share that owned the rights to a remarkable franchise: the Harry Potter novels. The risks then were that the shares were overpriced because of all the fuss, that Bloomsbury might turn out to be little more than Harry Potter, and when the fuss about the wizard died down, that would not be much at all. There was also the growing fear that Amazon and its Kindle would wreck the business models of traditional publishers by driving the prices of books down and taking a big cut of the profit. Maybe now Bloomsbury is adapting to these challenges, and it is quietly getting on with making money.

There is a good chance I might understand the business because I have worked in publishing and I spend a lot of time in bookshops and libraries. Bloomsbury meets the Base Filter+ criteria easily. It has no debt, and earned more profit in cash terms than accounting terms. It should fit in my circle of competence.

Checking the basic numbers

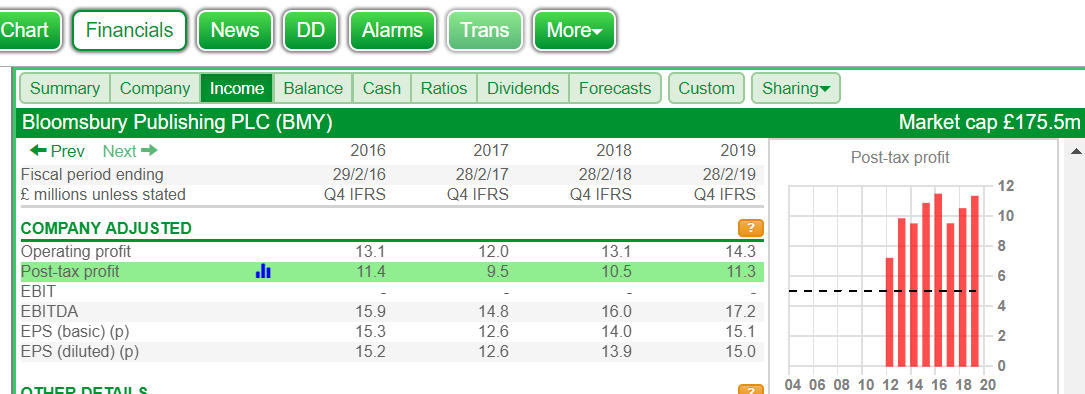

Some basic arithmetic reveals that Bloomsbury’s £9.2m net profit is just shy of 6% of £162.7m turnover, not brilliant for a company that owns valuable intellectual property in the form of rights to books and information. Profit is a matter of opinion though, and scrutinising the Income tab of the Financials section of SharePad shows Bloomsbury has a different opinion than the one presented in its own financial statements. It thinks it earned £11.3m in the year to February 2019:

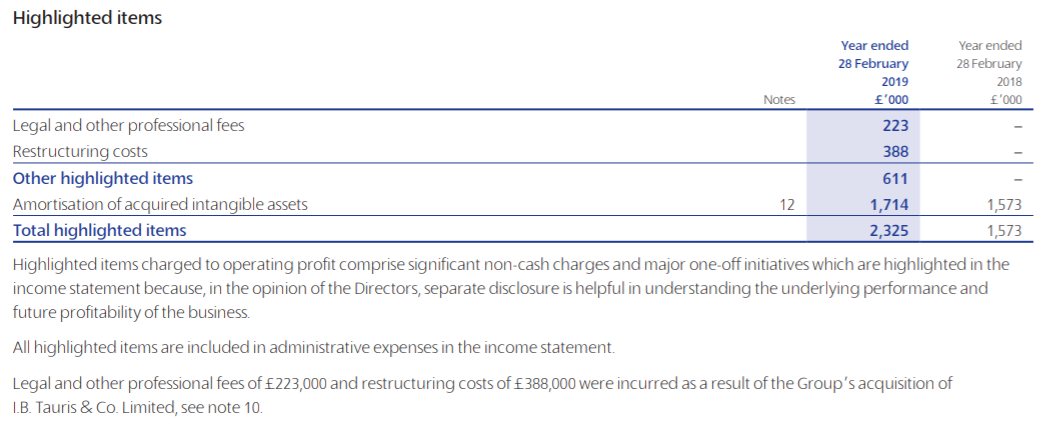

To find out why, we will need to take a look at the annual report. Bloomsbury calls its adjustments “highlighted” items, but other companies call them “exceptional” or “non-recurring”, and they are listed in Note 4 to the accounts:

All of the highlighted items are charges to the income statement relating to past acquisitions, which are genuine one-off events. The company’s adjustments probably do give a better indication of its performance, but it does not improve the net profit margin that much, to just shy of 7%.

The profit margin is only one part of the company’s overall efficiency at turning money it has invested into profit. The other half is capital turnover. A company makes money by charging more for its products and services than they cost to make (the difference is the profit margin) and by earning a lot in terms of turnover compared to the amount it has invested (capital turnover). By multiplying the two we get return on capital (see this article on the DuPont identity for a full explanation).

On the face of it, capital turnover is unremarkable too. You can find this ratio in the Ratios tab of the Financials section. It is 1.1, which means in 2019 Bloomsbury’s revenue was 1.1 times the capital invested in the business. Multiplying the company adjusted profit margin by capital turnover, gives a return on capital of just shy of 8%.

These are acceptable numbers, not extravagant ones, but wait a second: The capital figure requires some consideration because of those acquisitions. The one off events that are depressing profit, are probably also inflating the capital required to operate the business.

To balance the books when a company acquires another business, its accountants must decide what the money was spent on and recognise those items as assets on its balance sheet. Some of the assets will be physical, offices and computers say, which will wear out and require replacement and therefore more investment in future. Others, intangible assets, will be estimated to account for the difference between the value of the physical assets and the amount paid for the acquisition. These may be allocated under headings like the value of brands or customers, but the crucial point is if the company invests in them in future, for example by advertising the brand, or by recruiting new customers, the spending will be expensed, that is to say treated as part of the normal running costs of the business, and not capitalised through the creation of a new asset. So it is reasonable to regard goodwill and acquired intangibles as one-off investments. If the company will not create these assets in future in respect of the businesses it currently owns, then we should not use them to judge how efficiently it turns investment into profit.

Adjusting the capital required to operate the business is not trivial because Bloomsbury recognises a plethora of intangible assets on its balance sheet, some of which are acquired and some of which are internally generated, money spent routinely in developing products and computer systems and capitalised into assets. Separating them out is beyond the scope of this article, but the biggest intangible asset on SharePad’s balance sheet, goodwill, is always the result of an acquisition, so we can deduct it from capital employed.

SharePad uses the average of the most recent full-year capital employed and the previous year’s and we can find the number in the Ratios tab of the Financials Section under the Balance Sheet heading. It was £146.4m for the financial year ending in February 2019. You can find Goodwill listed in the company’s balance sheet (aka the Consolidated Statement of Financial Position). It was £44.9m in 2019 and £42.1m in 2018, so the average is £43.5m. Deduct average goodwill from average capital employed and we get £102.9m. Let’s call that operating capital.

A preliminary conclusion

Adopting the new figures: £11.3m net profit and £102.9m operating capital the return on operating capital after tax is just shy of 11%, which is a respectable level of profitability if it can be sustained. If we had deducted acquired intangible assets it would be a little higher still.

Bearing in mind free cash flow exceeded even the company adjusted net profit figure, Bloomsbury could be a good investment – if it can sustain or improve on these figures and we can buy the shares at a reasonable price (which we can, judging by its PE ratio).

To gain confidence in the future, we must examine Bloomsbury’s strategy. But I can already tell you one thing. Harry Potter is still working his magic.

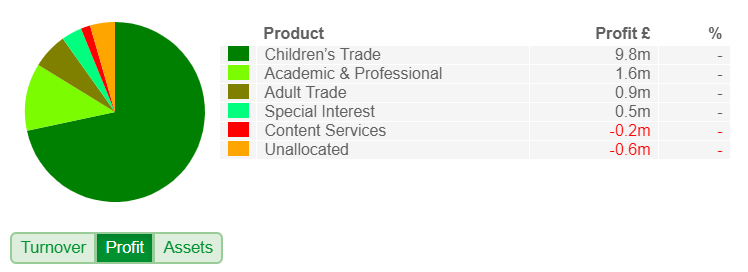

Despite the acquisitions, children’s books are still Bloomsbury’s biggest source of revenue:

They are by far its biggest source of profit:

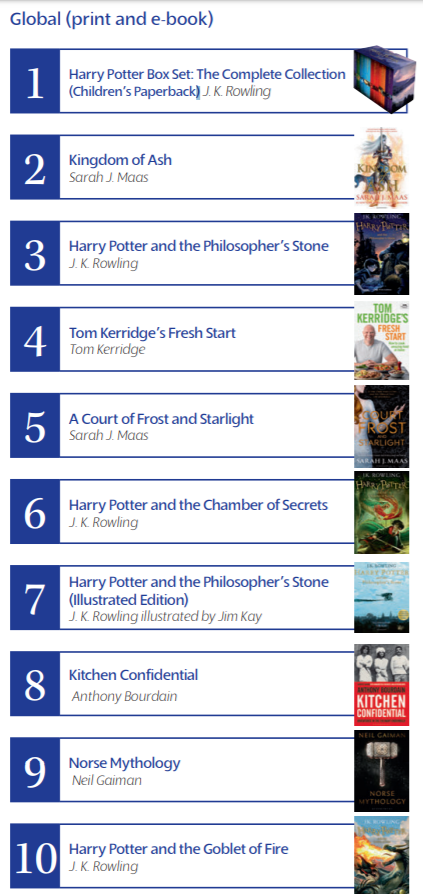

And five of its top ten bestsellers in the financial year, were about you know who:

Wow. Maybe Bloomsbury is still not much more than Harry Potter.

*Net borrowings as a percentage of capital employed is not one of SharePad’s standard statistics. When you add an item to a filter, or a column to a table, you can choose to combine two ratios. I combined net borrowings (including operating leases and pension deficits) “as a % of” capital employed.

SharePad has a number of gearing and debt:capital ratios that do a similar job.

Richard Beddard.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.