Holidays are great for switching off from the stresses and strains of the daily grind and concentrating on what’s really important in life. I’ve just had three weeks away from work – I can’t remember the last time I did that – spending time relaxing with my family and doing jobs around the house that have been neglected for too long. It has been my best break for years and I feel so much better for it.

One of the things I vowed to do was to switch off from all things to do with investing and the stock market as well. There was no looking at share prices, I turned off Twitter and just read the sports pages of the newspaper.

I must admit that I found this truly liberating. It also made me realise that this is what I should be doing all the time but like many others I occasionally find it difficult. Generally I am pretty good at staying disciplined but it is easy to fall into bad habits.

The experience has made me realise more than ever that many of us make investing more difficult and over complicated than it really should be. I am guilty of this from time to time. For example, I can sometimes over analyse things which might be very interesting to me but don’t really make that much difference in terms of what I am trying to achieve. Like most humans I also make mistakes as well.

So I am now resolved to make my investing more simple and focused and have devised an updated blueprint to try and achieve this. I have pinned this to the wall in my office to keep me on this task. The main points are described below.

This is not a plan for trading shares or short-term investors and is certainly not the only way to invest for the long term. Most of this is just common sense and is not difficult.

What I think is important is setting up a structure and process for your investing and having the discipline to stick to it. This will allow you to stay focused on your goal when others are obsessing about the day to day changes in stock markets.

Focus on businesses not stocks

It’s too easy to see shares as numbers on a computer screen or in a newspaper. They are not. Shares represent a part ownership in a real business. Ultimately, it will be the long-term success of a business and its ability to increase its profits that will determine whether you will make money.

Know what you are looking for in a business

Whatever style of investing you intend to follow, set out the characteristics of the businesses you would like to invest in. Have some flexibility from time to time as you are unlikely to find a company that meets all of your criteria all of the time.

Here’s my list of main criteria (Note that I would use different metrics to look at financial companies or utilities):

- Do you understand how a company makes money? I look for simple businesses which I can understand. If I can’t explain what it does to a friend in a couple of minutes then it’s probably too complicated.

- What does the company do that others can’t? This is a test of a company’s likely staying power and its ability to keep growing profits in the future. It is often referred to as the company’s economic moat. I am looking for high quality businesses with products or services which are hard to copy. (Check out my article on high quality companies and economic moats here).

- A track record of sales and profits growth.

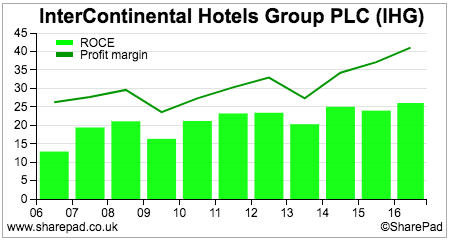

- Sustainably high returns on capital employed (ROCE) and high profit margins. Ideally, I am looking for businesses with ROCE of at least 15% backed by profit margins of at least 10%. These are signs that a company has defendable, high quality profits. High profit margins are a form of protection against a downturn in trading. Low margin businesses can become loss making businesses when times get tough.

For example this means that I might be more interested in a business such as InterContinental Hotels Group which has high ROCE and profit margins

…than one like Computacenter which has a decent ROCE but low profit margins.

- Recession resilience – I am looking to hold shares for a long time which means that I want to own something that has historically held up well in a recession. This means that I don’t tend to invest in cyclical companies such as house builders or manufacturing companies. Usually, the first thing I do when I look at a company is to see how well its profits held up during the 2008-09 recession. If they fell sharply then my interest in the business tends to end quickly.

- Does it pay a dividend? I like dividend-paying companies. It is usually – but not always – a sign that the company’s profits and underlying cash flows are real. I also don’t want to be entirely dependent on the stock market for my returns from an investment. Dividends give me a tangible return independent from the stock market.

- Low or no debt and absence of big pension fund deficits – Debt-like liabilities eat up a company’s cash flows and reduce the amount available for shareholders or reinvestment in the business.

- Turns profits into cash flow most of the time – Operating cash flows should be more than operating profits. If a company cannot do this it may be a sign of aggressive accounting or a business which requires too much working capital to grow. I also want to see reasonable amounts of free cash flow (trading cash flow less tax paid and capex) but it is important not to dismiss companies that are investing whilst maintaining high levels of ROCE. Ashtead (LSE:AHT) has been a good example of such a company.

- The ability to keep on growing profits in the future – This is the most important criteria of all. A company can have lots of great qualities but if it can’t grow its profits you are unlikely to make a lot of money from owning its shares. The company must be selling its products into attractive markets with a good strategy.

- The Intelligent Investor – Benjamin Graham.

- Quality Investing: Owning the Best Companies for the Long Term – Lawrence A. Cunningham, Patrick Hargreaves, and Torkell T. Eide

- Invest in the Best – Keith Ashworth Lord

- The Little Book that beats the Market – Joel Greenblatt

- The Zulu Principle – Jim Slater

- The Art of Company Valuation & Financial Statement Analysis – Nicolas Schmidlin

- Accounting for Growth – Terry Smith

- The Manual of Ideas – John Mihaljevic

- Lessons from the Successful Investor – Robin R. Speziale

- Free Capital – Guy Thomas

Don’t overpay for quality companies

I am not a momentum investor and will not pay really high valuations for companies even if they are growing quickly and people expect analysts’ profit forecasts will increase. I accept that this means I will lose out on a few money-making opportunities but high valuations mean high levels of risk.

This is because they reflect high expectations of future profits growth. As soon as a highly valued company disappoints on profits its shares tend to get hammered. I am not clever enough to get in and out of expensive shares before the music stops so I don’t try to do so.

This means I tend to place a limit on the price I will pay for a company’s profits or cash flows. High quality businesses do not often sell for cheap prices but I tend to limit myself to paying no more than 20 times their current cash profits. I will occasionally make an exception to this rule if I believe the company is of exceptionally high quality but not by much.

Avoid information overload

The internet and the everyday use of smartphones means that we can be bombarded with information all the time if we let it happen. However, this can play havoc with your mindset as a long-term investor.

When it comes to information less is more and quality trumps quantity every time.

Resist the temptation to check share prices and the value of your portfolio too frequently. You will feel great if its value is rising but maybe not so good if it is falling which might cause you to sell a good share. Accept that share prices going up and down is part and parcel of stock market investing. If you can’t accept sharp falls in value then put your money in a savings account instead.

Avoid bulletin boards. Many of them are full of people ramping their own investments or criticising people who don’t agree with them. Twitter can be a little bit like this but you can choose who you follow. I follow some very smart and interesting people on Twitter and learn a lot from their tweets. It’s very easy to become addicted to Twitter and spend too much time on there. Going forward I will limit my time on there to once or twice a day for a few minutes at a time at most.

What you should spend your time concentrating on is the performance of the business you have invested in. This means scrutinising its financial results every three or six months. You can sign up for email alerts from companies so that you can get this information when it is released to the stock exchange. If you are a SharePad or ShareScope user you can set up news alerts for shares in your portfolio.

Be patient and do nothing

Patience can be in short supply amongst investors. Many are looking to get rich quick and trade in and out of shares in order to do so. This can be very stressful and expensive due to high trading costs.

One of the factors behind Warren Buffett’s investing success has been his ability to own shares in good companies for a long time and let the power of compound interest make him rich. Terry Smith in the UK has also been very good at doing this in recent years.

Try to trade as little as possible. I do not automatically reinvest dividends but use them to build up a cash balance to fund new investments.

Sell bad businesses not bad stocks

I will only usually sell a share if I become uncomfortable with the business performance of a company. I will also sell shares – or some of them – if they become very expensive (say over 30 times cash profits).

If a business is performing well but its shares are out of favour then I will usually look to buy more shares. Sometimes it can take a long time for the true value of a company to be realised by the stock market.

Read lots

I have found that one of the best ways to improve as an investor is to read a lot. In my opinion, there is far more value in reading books than listening to the daily chatter. I am always on the lookout for new books and have a huge backlog.

Here are ten books which I have found very useful:

I would also add Warren Buffett’s shareholder letters to the above.

Above all else, I find reading company annual reports invaluable. There is also some great industry and company information to be found in admission documents and prospectuses.

Get out and talk to people

Whilst the internet has made life easier for private investors you can learn a great deal from talking to people. I know of private investors who are brilliant networkers and greatly enhance their knowledge by talking to companies.

If you are prepared to put in a bit of legwork then you can learn a great deal from what is going on in the public domain. Peter Lynch talked about this in his excellent book One up on Wall Street. Just talking to people who like certain shops and products can be very informative.

Getting out onto the streets can be a great way of spotting changes in trends in businesses. One of my oldest stockbroking friends was simply brilliant at doing this.

In his early career he used to specialise in smaller companies based in the North of England. He noticed that a local stock market-listed bathroom supplier was piling up stocks at its warehouses next to the motorway and saw it is as a sign of weakening demand. He was accused of peddling “northern tittle tattle” by a City fund manager but was proved right a couple of weeks later when there was a profits warning.

My father in law – a chartered surveyor – was very good at weighing up the fortunes of the building industry and local brick company just by looking at the stock levels in the local yards.

As a smaller company analyst in the early 2000s I started following a company called Ultraframe – a manufacturer of conservatory roofing systems. It was immensely profitable and had a high stock market valuation. It always puzzled me as to why this kind of business could be so profitable.

The company put it down to patented snap fitting technology which made its rooves faster and easier to install which brought down the cost of installation. I started looking at internet forums of conservatory installers who began talking about Ultraframe losing patent cases in the courts. I also talked to local conservatory companies who mentioned that they no longer used Ultraframe roofs because they were too expensive.

I was not too surprised when the profit warnings soon followed. The company went from making £33m of profits on £145m of sales in 2002 to a loss three years’ later.

This is an overview of my investing plan. Yours will undoubtedly be different but having one and reminding yourself of it from time to time works well in my experience.

Our new writer, Richard Beddard, has a similar investment approach to me. Read about it here.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.