One of the great things about investing is that there are lots of different ways for people to try and make money. This means that there is a style out there that will suit most temperaments.

Probably the most well known investing strategy is value investing. Yet I find that this term is frequently overused and misunderstood. This is because all investing is about value. No-one ever buys a share of a company thinking that they are going to lose money.

In the books and articles that I read, I frequently come across the assertion that value investing works and that over the long run it is better to buy value shares rather than growth shares. But how are private investors supposed to interpret this and apply it to their own portfolios?

In this article, I take a look at what value investing is, what it isn’t and how relevant it is for private investors in the context of the current stock market.

What is value investing?

We are all trying to buy shares for less than they are worth. My interpretation of the meaning of value investing in shares is that it is about trying to buy them for a lot less than they are worth. Put simply, you are trying to buy something that you think is worth £1 for 50p.

Value investing has its roots in the teachings of US investor Benjamin Graham. The most important part of his strategy was something he referred to as the “margin of safety”. By buying shares at a significant discount to what they are worth (sometimes referred to as their intrinsic value) the investor gives themselves protection against things going wrong.

Whilst Graham is seen as the father of value investing, it is less well known that he made most of his money from an investment in the insurance company GEICO. He made money because of GEICO’s growth over a number of years, not because it met the criteria of his value investing strategy.

Cheap is not the same as value

Many investors mistake cheapness for value. Just because a share looks cheap it doesn’t necessarily mean that it is good value. Many shares are cheap for a good reason – mostly because they are bad businesses with a bleak outlook.

A bottle of wine in the supermarket for £4 is cheap but if you end up pouring it down the kitchen sink because you can’t drink it then it has not been value for money.

Why value investing can work

The reason why value investing has been so successful is because human beings have a tendency to extrapolate recent trends. So if a company starts to struggle and its profits fall it is often assumed that it will continue to struggle. This leads to investors selling the shares and the share price tumbling. As a result a company’s shares can become significantly undervalued.

If the company’s problems are temporary and it can recover its profitability then it is possible to make fabulous profits from buying undervalued and depressed shares. This sounds simple and straightforward. It is not. Successful value investing often involves a lot of hours spent researching a company. You have to be fairly sure that a business can recover and that you are not catching the proverbial falling knife.

Is Graham’s approach to value investing redundant?

Absolutely not. If you can adopt the necessary mindset, patience and discipline then it is still possible to be a very successful value investor. Unfortunately today, if you are looking to adopt some of Graham strategies then conditions in the UK stock market are quite difficult to say the least.

His favourite strategy was to buy shares for less than two thirds of what he called their net current asset value (NCAV) per share. NCAV is defined as current assets (stock, debtors and cash) less all liabilities. No value was placed on the company’s fixed assets (such as buildings, plant and machinery). Graham reckoned that companies trading at such low valuations could be terrific bargains. However, he owned lots of shares meeting his criteria. It is difficult to do that today.

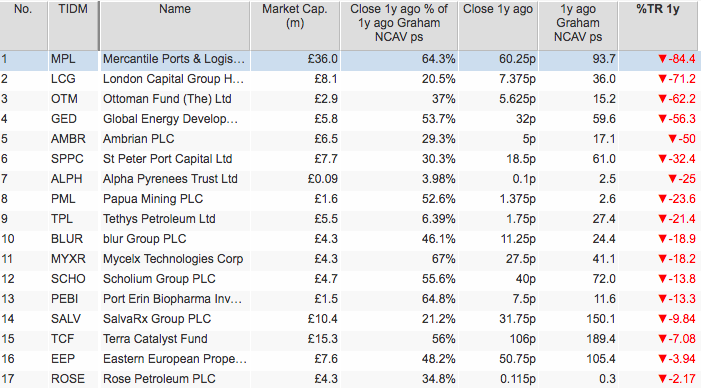

Below is a SharePad filter with some of the shares on the London Stock Exchange currently trading for less than two thirds of their most recent NCAV per share.

There are 40 shares which currently meet this criteria but most of them are related to companies with very small market capitalisations. Such stocks can be difficult to trade. They are often illiquid (not traded very often) and consequently expensive to buy or sell because of wide spreads (a big difference between their buy and sell prices).

A bit of crude back testing shows that buying some of the shares that met the criteria a year ago could have delivered some stunning results. Whether you could have bought these shares in meaningful amounts without paying eye-watering spreads is another matter.

However, you could have picked the wrong shares and ended up with massive losses (see table below). This shows the danger of blindly buying shares because they fit a numeric formula. It pays to do some research into the company’s future prospects.

Low PE investing

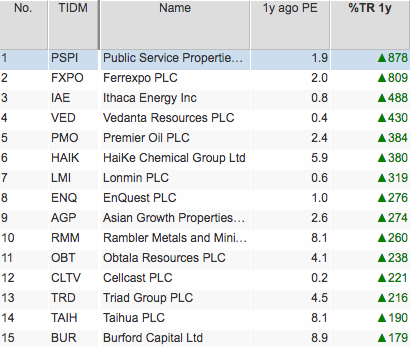

Buying shares with low PE ratios is another favourite strategy of value investors. Buying shares with a PE of less than 10 a year ago has seen 77 shares deliver total returns of more than 20% over the last year. Some returns have been spectacular.

But buying shares with a PE of more than 20 a year ago would have seen 104 shares deliver returns more than 20% over the last year. Granted, there have not been as many spectacular winners here.

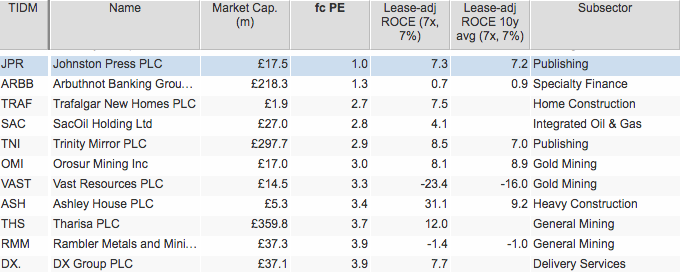

Low PE investing like Graham’s net net approach is no guarantee of success. Trinity Mirror shares have been trading on a low PE ratio for years but investors would have lost 30% on them during the last year.

Some current very low PE shares are shown below. I’ll leave you to try and work out whether they are good value or not.

Earnings power value (EPV)

My preferred value investing approach is earnings power value or EPV for short. (To read more on this way of valuing companies click here). EPV values a company’s shares based on its last reported trading profits (EBIT) staying the same forever.

If you can buy shares at a substantial discount to its EPV then you might have bagged yourself a bargain. As with most strategies, it comes with a few caveats:

- It is not suited to cyclical companies where profits are at or close to cyclical highs (e.g. Housebuilders).

- Forecast profits should be expected to be higher than the last reported profit. Otherwise you might be buying into a declining business.

- Debt levels and pension deficits must not be increasing significantly as this reduces EPV per share.

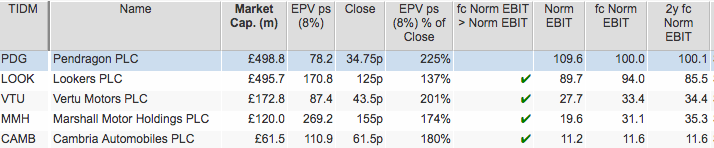

Are car dealerships screamingly cheap?

Sometimes whole sectors can look really cheap on this measure. One example at the moment is the car dealership sector. These companies are currently trading at huge discounts to their EPVs.

The stock market is essentially saying that the sustainable profits of these companies are going to collapse. Certainly, the UK new car market is cooling down and the fall in the value of the pound will push up their costs. But profits are still expected to increase for the next two years for Vertu, Marshall and Cambria.

Analysts forecasts are often wrong but there could be a case for saying that there is too much pessimism priced in here. If you consider yourself to be a value investor then perhaps car dealerships are worth spending some of your research time on.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.