Many investors like to build a portfolio of individual shares and even bonds but for some investors, investment funds can be a useful alternative.

For example, some investors may want to have a degree of control over their investments but don’t wish to dedicate the time to choosing and managing a lot off individual investments.

Then there’s a group of people who don’t have a large amount of money to invest but want to invest small amounts on a regular basis. For example. a young person who is just beginning a savings plan may only have £50-£100 spare each month which makes it difficult to buy individual shares given the costs of commission and stamp duty.

Most investors also aim to spread their risks by investing in different geographical regions (like Europe, Japan or China) and other asset classes like bonds and commercial property. This is called diversification.

In all these cases, some kind of investment fund may be an attractive proposition.

In practise, many investors build their portfolios using a combination of individual investments and investment funds.

SharePad and ShareScope both contain a lot of information on investment funds and help you find those with the best performance and the lowest costs.

In this article, I’m going to take you through the basics of investing in different types of investment funds. In another article, I will show you how to use the analytical tools in SharePad and ShareScope to help you find the right fund for you.

Why use investment funds?

As I’ve said above, investment funds can be a very useful way to save for the future and build up your nest egg. They are sometimes referred to as collective investments because lots of people contribute their savings into a pooled fund.

Collective investments also allow investors to easily buy into foreign investments, or to target specific investment goals such as income or capital growth. You can even invest in particular sectors or themes. By investing in funds, investors can spread their money across lots of different investments and lower their risks by not having all their eggs in one basket.

As with most things in life there are a few drawbacks as well. Some professional money managers aren’t very good at beating the performance of the investment markets as a whole. There’s also the risk that a manager might leave the company they are working for only to be replaced by a less capable one. Then there’s the risk that an investment fund gets too big and finds it difficult to invest in smaller companies that can make a big difference to the overall growth of the portfolio.

In this article I am going to talk about three kinds of collective investments that you might consider using:

- Open ended investment companies (OEICS) and unit trusts – which I will refer to as “funds” from now on.

- Investment trusts

- Exchange traded funds (ETFs)

OEICS and unit trusts (Funds)

These two types of fund are open ended and are very similar in makeup. Open ended means that a fund can create new units when investors put fresh money into the fund. They can also cancel units when investors decide to sell and cash them in. Closed end funds can’t do this but I’ll talk about them in a little while.

Trusts: In a trust the money and assets are held by a group of trustees. The money is invested by a fund manager. There is a deed of trust between the fund manager and the trustees.

When you invest in a fund you are investing in a portfolio that is managed by a fund manager. The fund holds a portfolio of investments that is made up of all its investors’ individual stakes in it. There are lots of different types of funds such as:

- Income funds that might provide you with money to live on.

- Growth funds that concentrate on increasing the capital value of your investment.

- Geographic or specialist sector funds. For instance you might want to invest in areas such as European shares, infrastructure or commodities.

- Index tracking funds such as one that tracks the value of the FTSE 100.

- Bond funds

- Property funds

Funds which require the manager to select the investments for the portfolio are termed “actively managed”. Tracker funds, which simply mimic the composition of an index, are termed “passive”.

When you invest money in a fund you are issued a number of “units”. These can be income units which pay out interest or a dividend to the unit holder. Or they can be accumulation units where any income paid out by the fund is automatically reinvested to buy more units which allows the investor to build up the size of their investment in the fund.

Costs and pricing

Investors usually have to pay fees for having someone else invest their money for them. Sometimes there is an initial upfront charge levied by the fund but if you are buying them from your broker these are often drastically reduced or waived completely.

Then there is an annual management charge (AMC) paid to the fund manager. These can range from anything as low as 0.1% for funds that just track a stock market index – and don’t require a lot of work – to more than 2% for more specialized actively managed funds.

Funds will also quote investors something known as a total expense ratio (TER) or ongoing charge figure. This will include the annual management charge plus other costs such as legal, audit and administration fees. However, other significant costs such as broker commission fees, stamp duty and spreads (the difference between the buying and selling price of investments in the fund) are not included and can eat into the value of an investment. These shortcomings also apply to the TERs of investment trusts and ETFs as well.

Most funds have a single price in that the buyer and seller pay are quoted the same price. This price is the net asset value per unit (the value of the fund divided by all the units in it). Say a fund’s total portfolio has a value of £10 million and there are 1 million units that have been issued, the net asset value (NAV) per share would be £10.

There may be some additional charges which are disclosed separately. For example, there may be a deduction for dealing charges incurred when buying and selling shares in the fund.

Some unit charges have dual pricing, where there is a difference between the buying and the selling price. This is to reflect an initial charge of buying the fund but this type of pricing is not very common these days.

Tax

All gains within a fund’s portfolio are exempt from capital gains tax. The dividends paid to the fund from companies will usually be taxed at source (at a rate of 10% for UK dividends) after which there is no further tax liability.

Any income received by the individual investor and any capital gains made on the sale of units are exempt from tax if the fund is held within a tax-free account such as an ISA or a SIPP. Investors also do not have to pay any stamp duty when they invest in a fund.

Looking at funds in SharePad & ShareScope

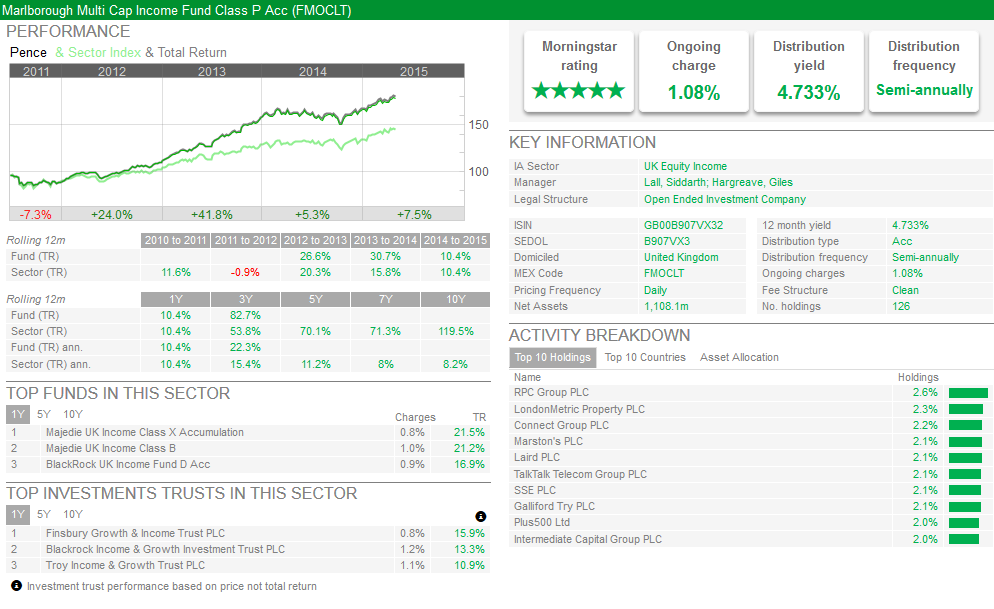

In ShareScope you can add a variety of information for funds in the form of columns – performance over different timeframes, ongoing charge, yield etc. In SharePad, more information is provided such as top ten holdings and this can be found on the Summary tab in the Financial view:

It includes lots of useful information on things such as fund performance, ongoing charge, the level of income you would receive and alternative, similar investments that you might want to consider.

Investment trusts

Investment trusts aren’t actually trusts, they are companies whose main activity is to run and manage an investment fund. Unlike funds, investment trusts are closed end funds. This means that they don’t issue new units to attract more investors. Instead the existing units, or shares, are traded on the stock exchange like company shares.

The portfolio of an investment trust tends to be more stable than a fund because the fund manager doesn’t have to worry about new money coming in or disrupting the portfolio’s strategy by selling investments when investors want to cash out.

To invest in an investment trust you can place an order with your broker in the same way that you would for company shares. The transaction will normally occur immediately.

One of the main differences between investment trusts and other funds is that they are allowed to borrow money (known as gearing). Gearing magnifies the returns of the investment portfolio for shareholders when markets are going up. However, they also magnify the losses when markets are going down. Heavily-geared investment trusts are therefore more risky and you need to look at this factor when you are thinking about investing in one. In contrast, the value of a fund will move in line with the value of its underlying investment portfolio.

Premiums and discounts

The prices of funds are determined by their net asset value (NAV), but those of investment trusts are determined by the forces of demand and supply on the stock market. This means that the price of an investment trust can be less (known as a discount) or more (known as a premium) than its NAV.

Discounts occur for a variety of reasons. Often there is low demand for an investment trust because there is poor sentiment towards the assets or countries that it is invested in. The other main reason for a discount is poor portfolio management. As a general rule of thumb, the better the track record of the fund manager, the lower the discount to NAV. However, the presence of discounts is often cited as a reason why some people don’t like to put their money in investment trusts. Many excellent investment trusts, however, trade almost permanently at a discount to their NAV.

Good management can see investment trusts trading at a premium to their NAV. Premiums also occur if the trust is invested in the latest hot sector and there is a shortage of competing funds.

I will be writing another article which delves into how to analyse and compare these different types of investment fund.

The size of premiums and discounts of investment trusts change depending on what’s going on in the general investment markets. Keeping an eye on the trust’s historic relationship between its price and NAV is an important factor to consider when you are thinking about investing in an investment trust. I’ll talk more about this in the next article.

Costs

Investment trusts are often recommended as investments because they can have lower annual management fees than funds. This may have been true in the past, but the banning of commission payments from funds to financial advisors has seen funds become a lot cheaper and more competitive.

There are also additional costs to consider when buying an investment trust. Because they are shares listed on the stock exchange, you have to pay broker commissions and stamp duty as well as incurring a bid-offer spread (the difference between the buying and selling price of a share). These costs can add up and can make a significant dent in the size of your initial investment (more on this in my next article).

Tax and investment trusts

Investment income and capital gains in the portfolio are typically exempt from tax. The investor may have to pay tax on income and capital gains if the trust is not held in a tax-free account (e.g. an ISA or SIPP).

Looking at Investment trusts in SharePad & ShareScope

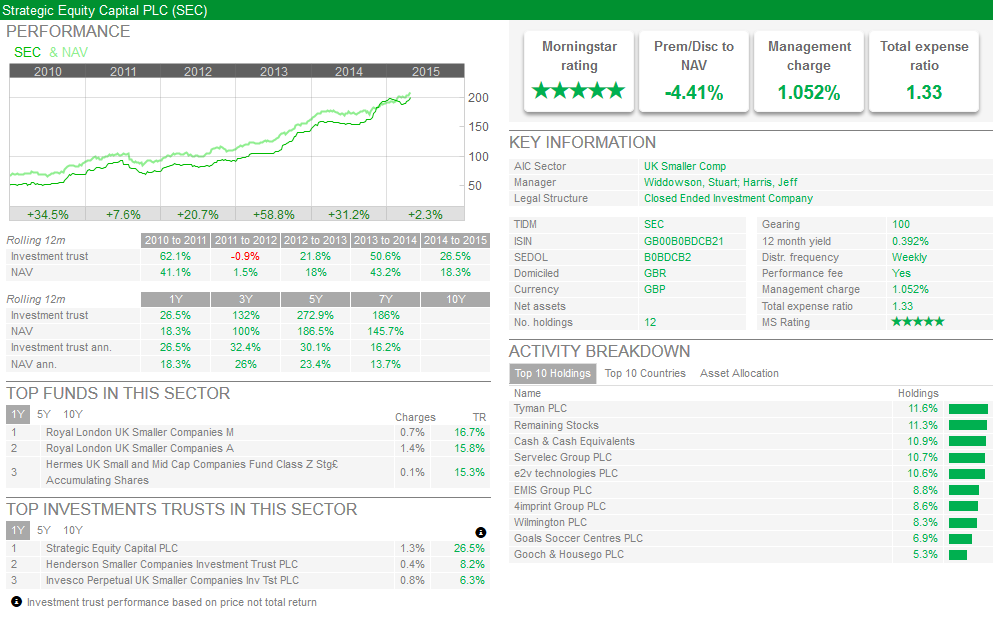

In ShareScope you can add a variety of information for investment trusts in the form of columns – performance over different timeframes, ongoing charge, yield etc. In SharePad, more information is provided such as top ten holdings and this can be found on the Summary tab in the Financial view:

As with funds, this summary includes lots of useful information on things such as fund performance, ongoing charge, the level of income you would receive and alternative, similar investments that you might want to consider.

Exchange traded funds (ETFs)

ETFs have become very popular with investors in America and have started to gain favour with lots of UK investors too.

ETFs are open ended funds (they can create fresh shares) that are listed on the stock exchange and they are bought and sold like shares. They generally track the price of stock market indices, commodity prices, exchange rates or economic indicators and allow investors to build a portfolio with exposure to lots of different investment assets for a significantly cheaper price than buying a specialist fund. You can also invest in ETFs that make money if an index or price falls (known as going short) or use borrowed money (leveraged ETFs).

ETFs are popular for a number of reasons. Firstly, because they are tracking an index their fees tend to be a lot lower than funds. Also they can be traded at any time during the trading day whereas funds only trade once per trading day. Unlike investment trusts, there’s no stamp duty to pay when you buy them but you will have to pay broker commissions and bid offer spreads.

Physical and synthetic ETFs

Many ETFs are based on holding a basket of investments based on the index they are trying to track. For example, an ETF tracking the FTSE 100 will hold the 100 different shares in their exact proportions in which they make up the index. This is a physical ETF because it is based on real assets or investments.

The alternative is known as a synthetic ETF. This is when an ETF provider enters into a relationship with another party who agrees to pay the total return of the FTSE 100 (known as a swap agreement) without actually owning the actual shares in the index.

Synthetic ETFs tend to be more common for assets such as commodities. However, they can be more risky as they are dependent on the other party (known as a counterparty) being able to pay the agreed returns. During the financial crisis of 2008, many banks who were counterparties in ETF agreements came close to failure which could have seen some painful losses for synthetic ETF investors. Owners of physical ETFs would have had a claim on real assets and were therefore in a safer position.

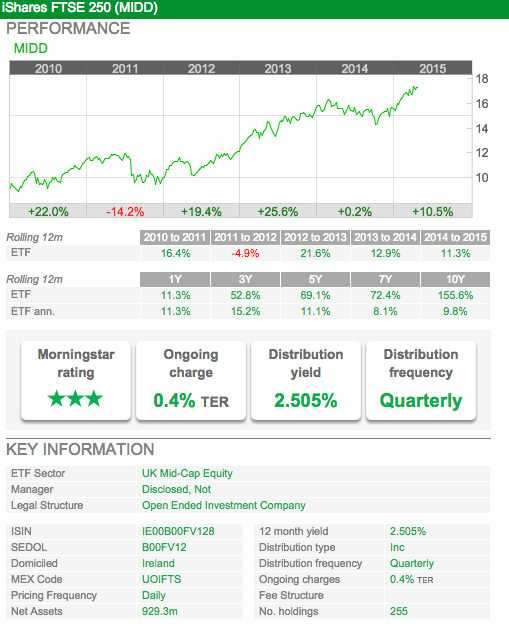

ETF information in SharePad

As with funds and investment trusts, SharePad provides a handy summary page for each ETF.

I will be writing another article which delves into how to analyse and compare these different types of investment fund.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.