Camellia has enjoyed incredible long-term NAV growth but recent years have not been very kind to earnings and the share price. Maynard Paton assesses the agricultural group’s eclectic assets, ‘value enhancement’ plan, revamped board and lowly valuation.

“I stress the long-term advisedly, because our entire emphasis is towards the development of a worldwide group of businesses which by their very nature require their managements to take a long view.

Many companies in the group are in excess of 100 years old. These enterprises have acquired particular skills, traditions and ethos, and we see ourselves more in the nature of custodians or trustees than as owners.

That is, we do not see these assets as objects or commodities or bits of paper that can be traded, but rather as living entities from which, if properly managed, we might earn an attractive return on our investment.”

You could be forgiven for thinking that statement was written by Warren Buffett to his Berkshire Hathaway shareholders. But the author was in fact Gordon Fox, then the chairman of Camellia, back in 1990.

By employing a very long-term investment approach, Mr Fox enjoyed great success building Camellia into a mini Berkshire-type conglomerate. But rather than textiles, insurance and banks, Mr Fox instead focused primarily on agriculture…

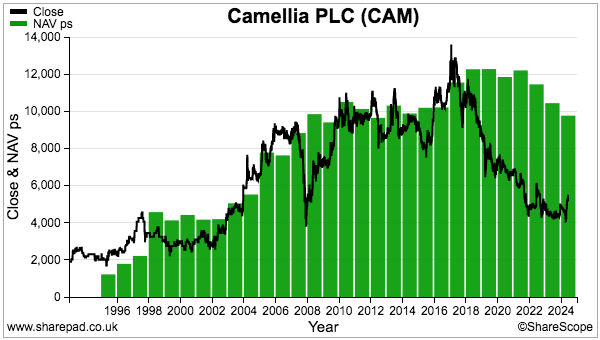

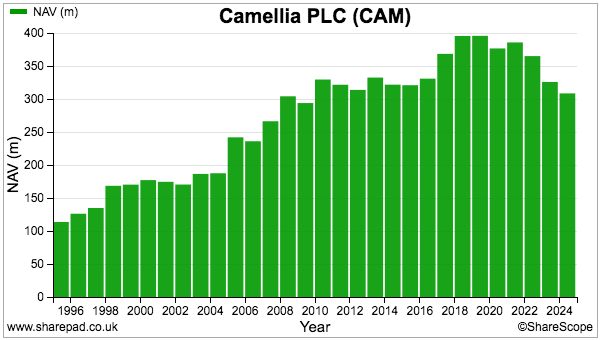

…and between 1969 and 1999 compounded Camellia’s net asset value (NAV) from less than £500k to £170 million — equivalent to a 21% average annual growth rate.

Camellia’s NAV has since advanced to approximately £300 million and is chock-full of cash and investments…

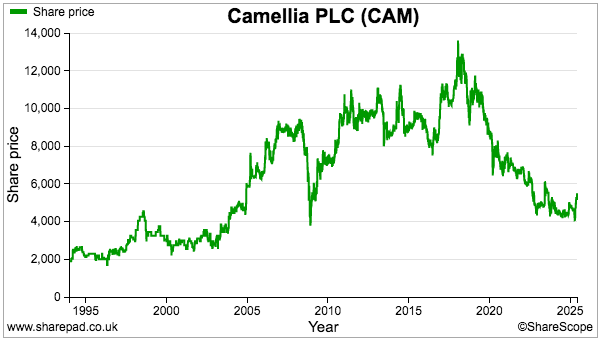

…yet the share price has declined 60% since its 2018 peak:

Investors can today buy at a 50%-plus discount to the value of the balance sheet.

So what exactly has happened at this NAV ‘compounder’? Is the NAV really worth £300 million? And have the £54 shares become a bargain?

Let’s take a closer look.

Introducing Camellia

Gordon Fox, a Canadian investor, became involved in what would become Camellia during the 1950s. Back then he acquired a small stake in Sephinjuri Bheel, a company quoted on the London stock exchange whose sole asset was a modest tea garden in the Assam region of India.

Mr Fox then undertook “seemingly endless tea journeys to the East” and, by 1966, had joined the board of what was now renamed Camellia. His responsibilities included directing the Koober Tea Estate, a role that commenced a “long process of understanding the nuances and realities of tea and its production“.

Mr Fox was appointed Camellia chairman during 1968 and then became the group’s largest shareholder during 1969, when he backed a £250k rights issue to bolster the group’s then £200k portfolio of tea-plantation investments.

By 1976, Mr Fox had resolved to “secure, enhance and actively manage” Camellia’s tea interests and so increased the group’s small, ‘passive’ shareholdings into majority, ‘active’ stakes.

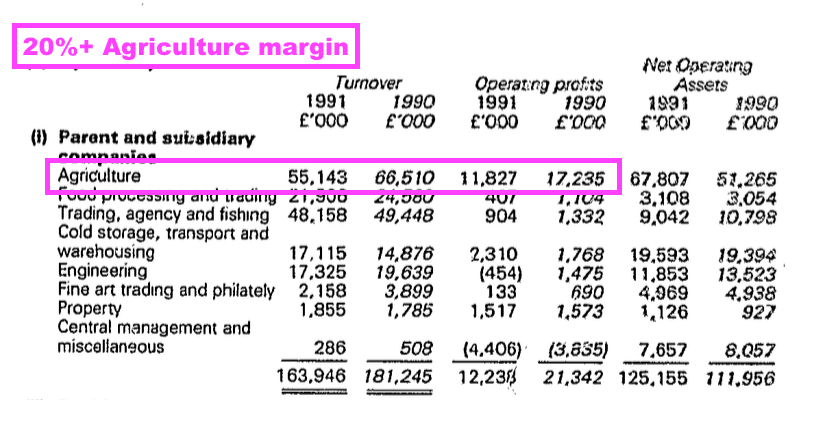

A major milestone occurred during 1990, when Camellia took control of another plantations conglomerate and accounting changes prompted the first full disclosure of the group’s trading revenue and profit:

At the time, a useful £21 million profit was scored from revenue of £181 million, with the agriculture division in particular boasting an impressive 20%-plus operating margin.

By 1990, Camellia’s tea operations in India and Bangladesh had been complemented by harvesting coffee beans, oranges and almonds in Malawi, Kenya and the United States. Other 1990 activities included food processing, fisheries, cold storage, engineering and, unusually, trading antiques and vintage stamps.

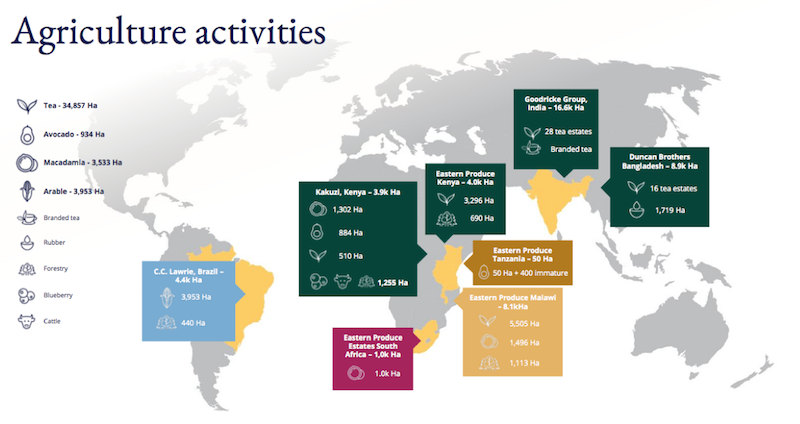

Following various disposals during the last decade, Camellia has reverted to its agricultural focus and, alongside tea plantations within India and Bangladesh, crops now include avocados, macadamia and blueberries while locations now include South Africa, Tanzania and Brazil:

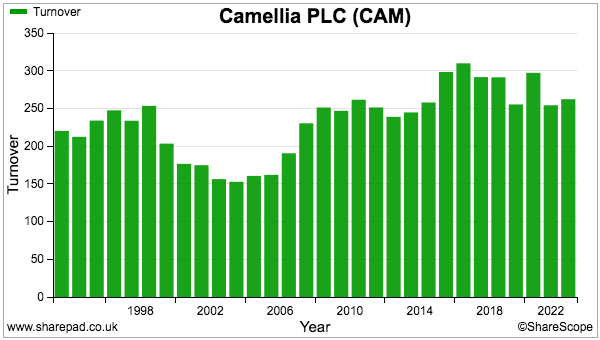

Camellia’s financial history is not the easiest to interpret given the group’s Berkshire-like web of subsidiaries, its numerous non-trading charges and the chunk of profits that accrue to minority owners. But the general picture is one of resilient revenue…

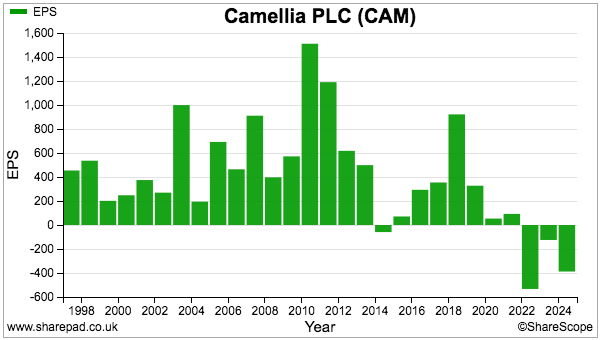

…alongside haphazard earnings that during recent years have taken a turn for the worse…

…which has led to NAV also taking a turn for the worse:

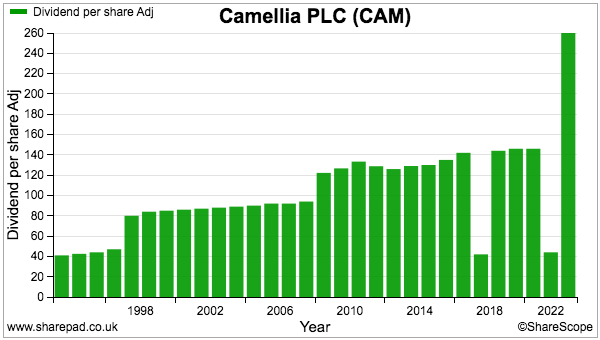

However, the dividend proved very reliable until the pandemic…

…and remarkably surged to a new high for 2024 after being suspended for part of 2023.

After joining the main market during 1949, the shares transferred to AIM during 2014 and the recent £54 price supports a £137 market cap:

Although the shares are back to where they were 20 years ago, extremely long-time shareholders should still have done very well.

For example, anybody backing Mr Fox when Camellia took control of its tea investments during 1976 at 80p has since enjoyed a 67-bagger, equivalent to a 9% 49-year CAGR before dividends. The payout during 1976 was 1.65p per share versus last year’s 260p.

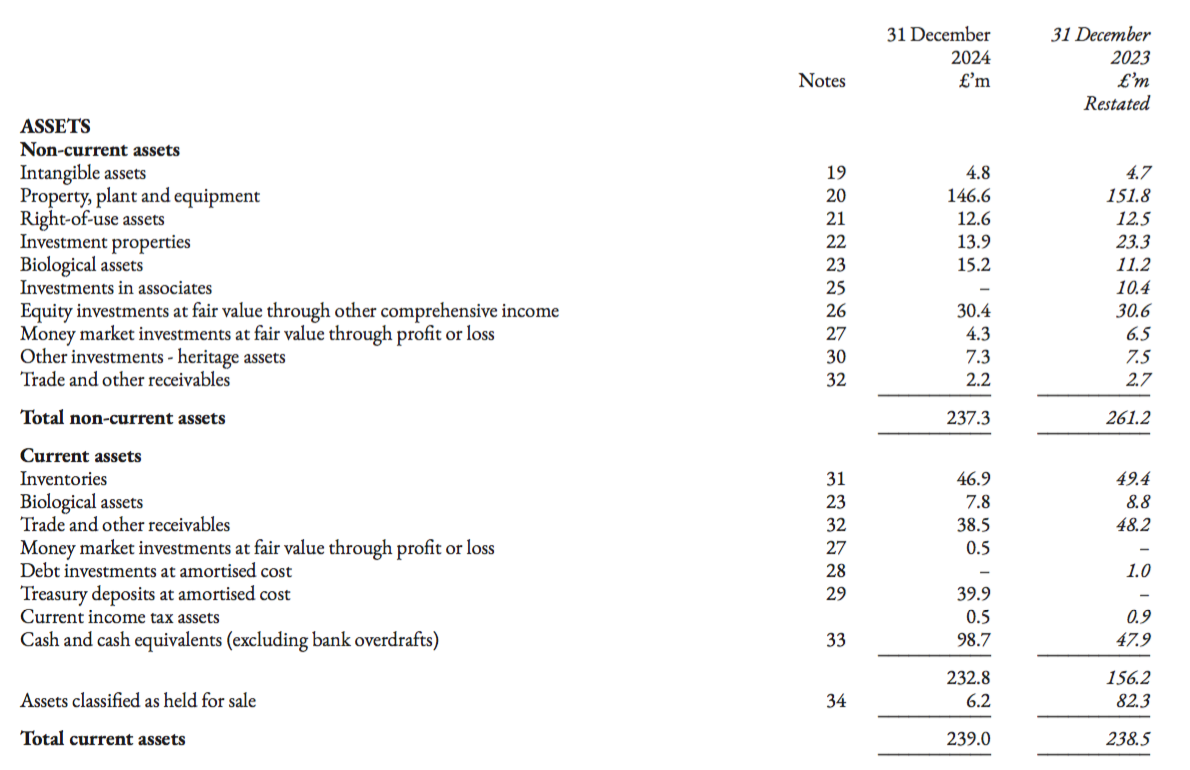

Balance sheet and agriculture profits

Camellia must have one of the stock market’s most eclectic collection of assets, which at the last count added up to £239 million:

Entries include:

- Cash of £99 million;

- US treasuries of £40 million;

- Investment properties of £14 million;

- Equity investments of £30 million;

- ‘Heritage assets’ — essentially a hoard of fine art, stamps and manuscripts — of £7 million;

- Money-market funds of £5 million, and;

- Property assets held for resale of £6 million.

Less bank debt of £19 million leaves net cash and investments at £183 million. Remember the market cap of Camellia at £54 is £137 million.

The agriculture part of the balance sheet totals £216 million and includes:

- ‘Bearer plants’ (i.e. plants and trees that grow crops) at £82 million;

- Land and buildings of £38 million;

- Plant, machinery and equipment of £26 million;

- Inventories (i.e. harvested crops) of £47 million, and;

- Biological assets (i.e. crops yet to be harvested) of £23 million.

The remainder of the balance sheet comprises net liabilities of £51 million, which consist mostly of trade payables and deferred tax that all appear above board. However, the group’s £9 million pension deficit probably requires greater contributions while ‘contingencies’ include a number of overseas tax disputes.

Given the market cap is much less than NAV — and even less than the net cash and investments — investors clearly have significant doubts about the £216 million book value of the agricultural assets.

‘Bearer plants’ in particular may not in reality be worth anything close to their reported £82 million — not least because these plants during the last few years have struggled to bear crops that convert into useful profits.

(Note that Camellia’s auditor does not provide extra scrutiny of the group’s agricultural assets through a ‘key audit matter’. The auditor instead deems Camellia’s intangibles — valued at less than £5 million! — as a ‘key audit matter’ that poses a greater risk of ‘misstatement’.)

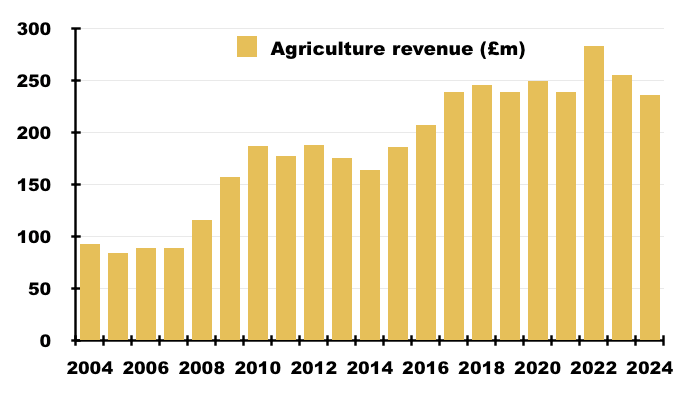

Despite agriculture revenue trending higher over time…

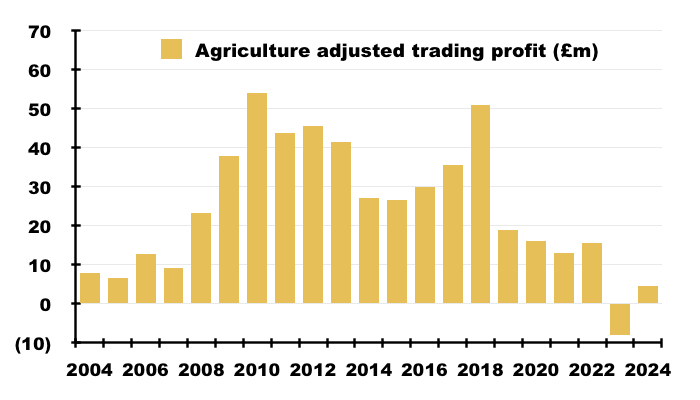

…agriculture profit has declined dramatically since 2018:

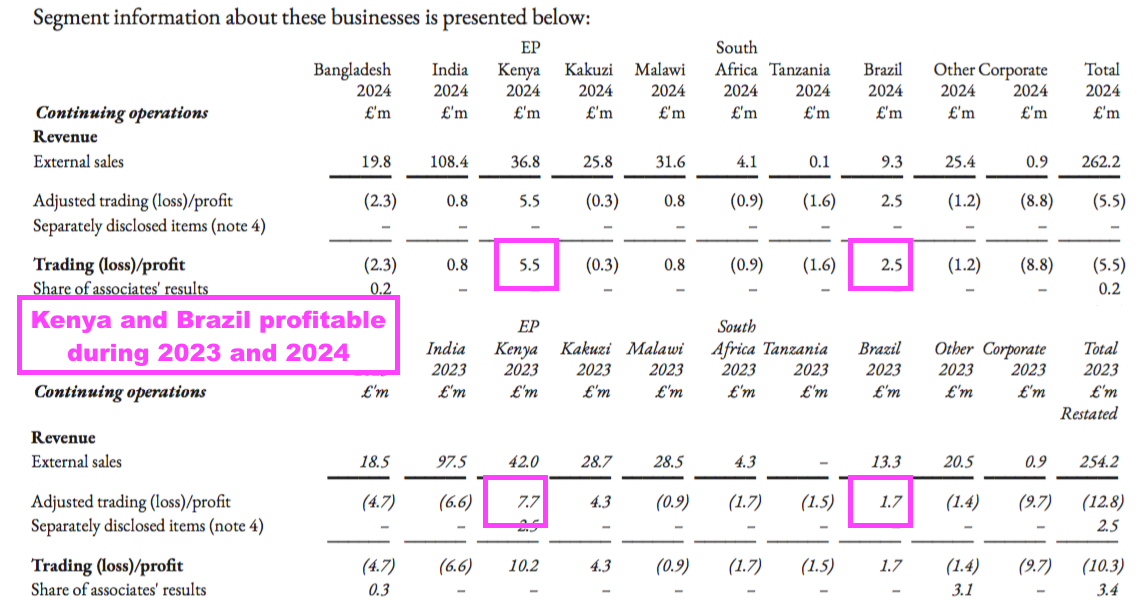

The agricultural woes are spread throughout the group, as only operations within Kenya and Brazil managed to avoid losses during both 2023 and 2024:

Camellia’s agriculture profit collapsed 60% during 2019 and the group then blamed the disruption on an “over supply of tea causing prices to fall” and the “relentless growth of the smallholder market”.

Such smallholders were said to have benefited from a “decrease in regulation” and could therefore “produce tea with fewer social and certification costs“.

The 2020 results then included this ominous prediction for the long-term economics of tea plantations:

“However, the world remains over-supplied with tea, which, combined with a desire across the industry to raise wages and living standards could lead to a long-term decline in the profitability of tea growing.”

Camellia may have limited scope to “raise wages and living standards” among its workforce.

True, the group paid wages of £98 million to 79,224 employees last year — equivalent to only £1,234 per person. But the lowly price of tea and the labour intensity of crop plantations restricts revenue per head to less than £4,000.

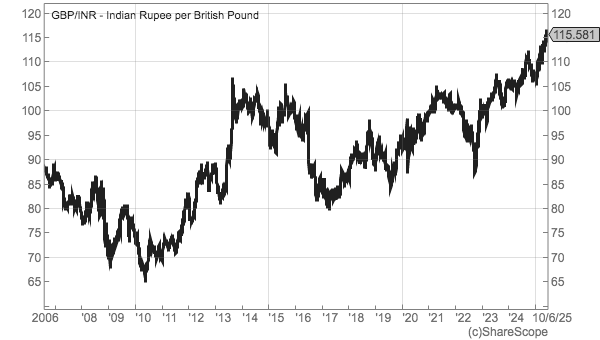

Alongside over-supply and wage inflation, Camellia has also cited greater distribution, energy and fertiliser costs for the absence of significant agriculture profits of late. Agricultural businesses are of course always exposed to adverse weather while their financial results, at least for UK shareholders, can be diluted by exchange rates.

For example, rupee-denominated tea profits will have deteriorated in sterling terms since 2017:

Other issues suppressing agriculture profits during recent years include a £16 million charge associated with allegations of employee abuse in Kenya and Malawi, and the disastrous £13 million purchase of Bardsley England, a Kent-based fruit farm that subsequently suffered persistent losses and had to be closed down.

All told, the favourable economics of tea plantations appear to have subsided significantly since the days of Gordon Fox. So much so, Camellia last month announced a ‘value enhancement plan’ (VEP) to revitalise the group and bolster shareholder returns.

Value Enhancement Plan

The VEP announced last month revealed three simple objectives:

- Improve operating results;

- Reduce overall risk, and;

- Invest in growth.

Proposed actions to enhance factory efficiency, workforce utilisation and crop management are set to cost between £23 million and £35 million a year — much greater than the £10 million expensed during 2024.

The VEP clarified the sudden dividend improvement to 260p per share would NOT be covered by a sudden earnings improvement:

“While the 2024 dividend of 260p is being funded out of reserves, the Board views 260p as a sustainable dividend due to the cash reserves that Camellia has and the expectation that successful delivery of the VEP will lead to a business that can deliver profits to consistently cover this dividend with the potential to then grow.”

However, Camellia does expect the VEP to one day enhance earnings and eventually cover the 260p payout by generating a 5%-plus return on capital:

“To cover the 260p dividend, the Group will need to, in the first instance, deliver a return on capital exceeding 5% with an expectation of higher returns further out which can support a growing dividend.”

Targeting a minimum 5% return on capital from the agricultural assets emphasises how Indian tea plantations and Kenyan avocado farms may no longer be the most productive of business activities.

In the meantime, a 260p per share dividend equates to £6.5 million and adds to the annual £23-plus million to be spent revitalising the group’s operations. With limited agricultural profits at present, the upgraded expenditure looks set to reduce the £99 million cash position during the next few years.

Management claimed during this VEP webinar that the agriculture division could in time earn a “decent return“:

“Q: Pessimists might say the VEP looks like more of the same — potentially another £100 million sunk in an agricultural division that has never earned its cost of capital. Why is this time different?

A: I think the last couple of years for sure has been a difficult period of time but we have really good quality assets here that have been built up over many years and they operate at scale, they’re commercially successful, they’ve got good management teams, they are producing crops that have enduring demand around the world and so we have confidence that actually run well with focus and where we’re utilising the assets to the optimal amount, these businesses can generate a decent return.”

Management also claimed the group’s NAV was “fair“:

“Q: The tender offer is at less than half of the tangible book value. Does this reflect the company’s outlook for these assets, and that they will need to be written down in the future?

A: No, all our assets have inherent good value, and we believe the book values are fair, and potentially offer upside.”

Camellia accompanied the VEP with a tender offer that ultimately spent £11m acquiring 8% of the share count at £54. That tender may prove to be a prudent investment should the VEP work out and validate the group’s NAV.

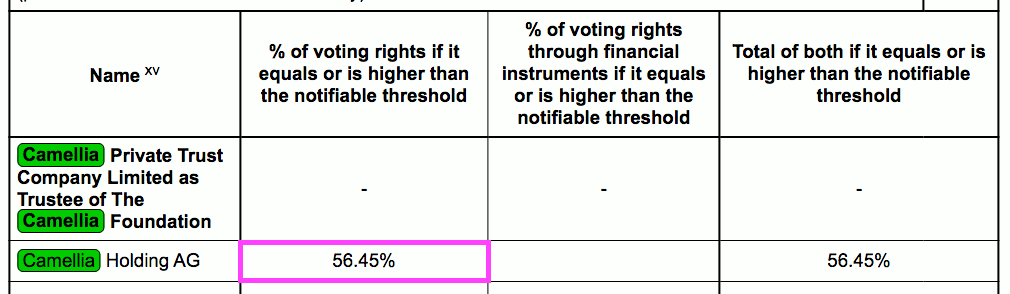

Note that Camellia’s largest shareholder, the Camellia Foundation, did not tender any shares and its ownership therefore increased from 52% to 56%:

Camellia Foundation and boardroom

The aforementioned Gordon Fox was born in 1929, and I must admit I have not verified whether he is actually still alive.

But I do know the large Camellia shareholding Mr Fox established during 1969 lives on through the Camellia Foundation, a Bermudan trust that spends its Camellia dividends and other income on “charitable, educational and humanitarian causes“. Companies House suggests the Foundation’s Camellia shareholding has never been cut since at least 1976.

I get the impression the Foundation has become more involved with Camellia during the last few years.

Form what I can tell, the Foundation had no Camellia board connections between Mr Fox’s 1999 retirement and 2020, at which point the Foundation’s chairman was appointed as a non-executive. That non-exec has since become Camellia’s chairman, while another Foundation director was appointed as a Camellia non-exec during 2021:

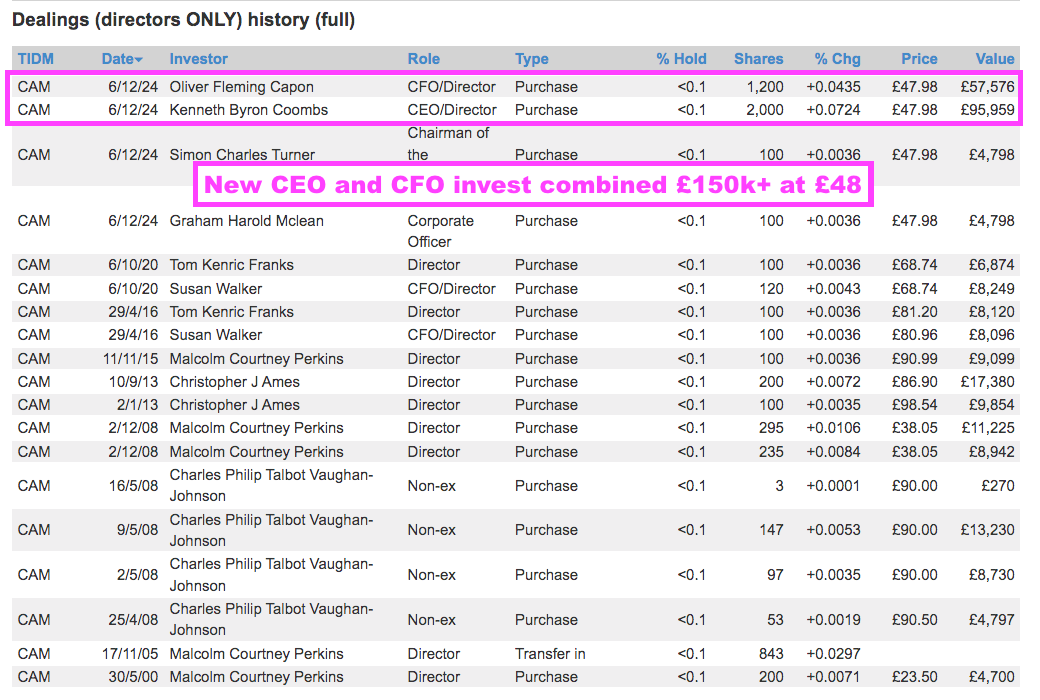

Appearing to reflect the Foundation’s verdict on Camellia’s deteriorating progress, a new chief executive was appointed during 2023 and a new finance director was appointed during 2024.

I note that an “extensive candidate search” over twelve months resulted in the group’s investment director becoming chief exec, who has since “used his experience of investment analysis in assessing the position of the operating companies and in formulating the future strategy for the Company.”

The protracted search for the new chief exec — that concluded with an in-house appointment — does make me wonder whether Camellia struggled to appeal to outside candidates with exceptional industry CVs.

I also wonder whether the new chief exec’s banking career means the VEP has been derived mostly from spreadsheets rather than visiting tea plantations and understanding the same “nuances and realities of tea and its production” as Mr Fox.

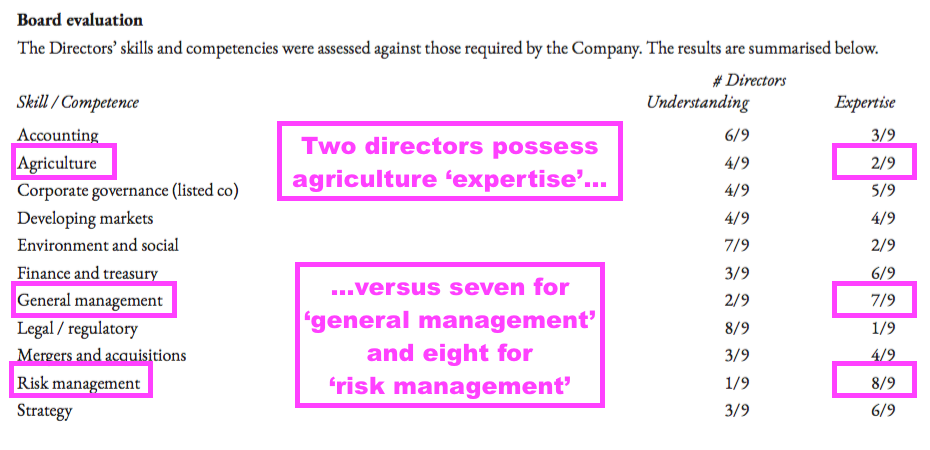

Indeed, only two of the nine directors are now agriculture experts…

…while seven are ‘general management’ experts and eight are ‘risk management’ experts.

Mind you, the chief exec and finance director have shown conviction to shareholders by undertaking the largest boardroom share purchases since at least 2000:

Summary and verdict

There’s a lot to like and dislike about Camellia.

The group appears delightfully ‘old school’ and something of a throwback to the British Empire with its tea plantations, fine-art collection and venerable properties…

…including the group’s former headquarters — a Grade I listed country house sited within 150 acres — currently on sale for £9.5 million.

Such assets can all now be purchased at a steep discount to NAV, and the tender offer implies both the board and the Camellia Foundation believe the shares are under-priced at £54.

But Camellia’s NAV is ultimately underpinned by the group’s agricultural operations, the recent profitability of which has been very sub-par and requires significant additional investment to even recover to a 5% return on capital.

And therein lies the ‘old school’ drawback to this business: times have moved on, global markets have evolved… and harvesting tea now seems unlikely to regain the lucrative economics enjoyed during the Gordon Fox era.

Much as I admire Mr Fox’s long-term investing and plantation accomplishments, he is no longer in charge and I speculate even he — a textbook buy-and-hold shareholder — would be questioning his approach when a holding declines to a price first witnessed 20 years ago.

All told, I worry the additional plantation expenditure will soon reduce that £99 million cash position and diminish the group’s NAV discount attractions. Although Mr Fox’s Foundation remains in for the long haul, I can’t say the balance sheet is truly worth £300 million and my hunch therefore is the £54 shares may prove to be only a marginal NAV bargain.

Until next time, I wish you safe and healthy investing with ShareScope.

Maynard Paton

Maynard writes about his portfolio at maynardpaton.com. He does not own shares in Camellia.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.