Cranswick is a UK-based food producer. It specialises in the production and selling of pork and poultry products. The sales mix of its business is as follows:

- Fresh Pork (34% of sales) – Cranswick is the third largest pig producer in the UK. Its own herd of outdoor reared pigs provides 18% of its own pig requirements.

- Convenience (37% of sales) – This business produces and sells cooked meats such as hams, sirloin beef and turkey crowns. It also produces continental food offerings such as charcuterie, olives, continental cheeses, pizza toppings, Italian pasta and pâté.

- Gourmet products (18% of sales) – premium sausages, bacon and pastries. Products include sausages made for Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference and Tesco’s Finest brands.

- Poultry (11% of sales) – Fresh and cooked chicken and turkey products.

Around 75% of Cranswick’s sales go to retail customers for their own label premium meat products. 20% goes into the foodservice sector such as pubs, hotels and quick service restaurants. Around 6% of sales are exported to Europe, the US and increasingly China.

The company has 15 production sites around the UK and has been adding new capacity in recent years.

Cranswick has delivered decent growth in sales and profits over the last decade. It has done this by selling more from its existing businesses as well as buying new ones. The company has a good record of investing in new production facilities to give it scope to grow in the future as well as introducing new and innovative products for its customers to buy.

In 2008, sales and operating profits were £559m and £36m respectively. For the year ending March 2018, it is forecast to have sales of £1,459m and operating profits of £90m.

Financial Performance

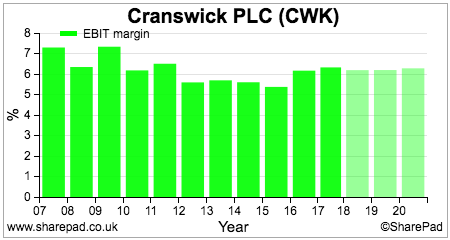

Cranswick is not a high profit margin business. This is largely due to it operating in a very competitive marketplace and selling to big supermarket customers that have considerable buying power (more on this later).

Profit margins have come down slightly from a decade ago but have been fairly consistent at around the 6% level since then. The business tends to operate on customer contracts which allow Cranswick to pass on some – but not all – cost increases such as pig meat.

Cranswick’s profit margins have been remarkably consistent and show that it has been a fairly resilient business. The company has been very good at investing in its production facilities in order to make its business more efficient over the years. This has been helpful in supporting its profit margins.

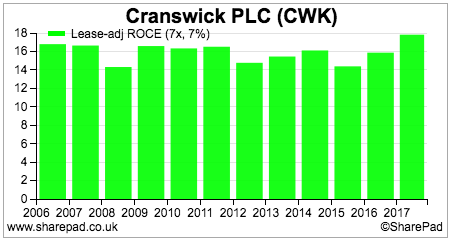

Return on capital employed (ROCE) has also been very consistent and is at a high level (just over 17% on a lease-adjusted basis in 2017).

I like to see businesses with this kind of stability in ROCE over an economic cycle. Whilst the future may turn out differently, Cranswick has clearly been a business that has been able to make good levels of profitability on the money it has invested. This is a sign of a high quality business in my opinion.

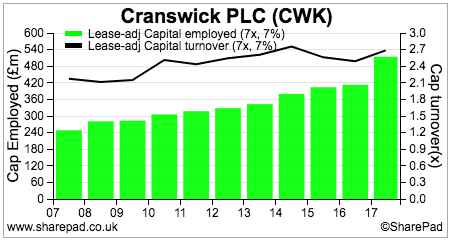

What’s been particularly impressive is that Cranswick has been able to keep its sales growing whilst increasing its capital invested. Capital invested has doubled in the last decade but capital turnover (the level of sales per £1 of capital invested) has improved as well as shown below.

This chart is telling us that Cranswick’s ROCE is significantly influenced by selling more products. For a business with relatively low profit margins this is a good sign.

The challenge for Cranswick is to maintain this impressive performance. Capital employed in the business has increased significantly recently on the back of new production facilities and acquisitions.

The company is also spending £54m on a poultry facility in Suffolk which will contribute to a large step-up in capital employed in 2018 and 2019. It would not be surprising to see Cranswick’s capital turnover and ROCE come down a little for a couple of years whilst this new facility gets up to full production levels.

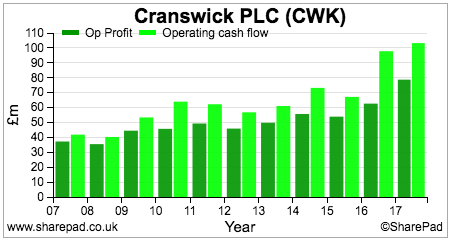

Cranswick passes the test of comfortably converting its operating profits into operating cash flow. This is the easiest test of cash conversion and one that Cranswick should be able to meet quite easily given its relatively large non-cash depreciation expenses on its production facilities. You would be worried if it could not convert operating profits into operating cash flow.

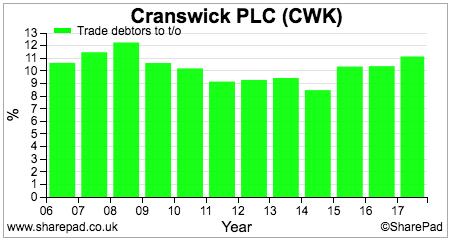

One of the key risks of selling large amounts to big retailers is that they have considerable buying power. This not only comes in the form of pricing but also in payment terms. Companies such as Tesco have become well known for using their suppliers as a form of credit by increasing the time they take to pay their bills.

For the supplier, this means having to wait longer for their cash which reduces operating cash conversion but also increases the amount invested in working capital and leads to a reduction in ROCE if it can’t be offset elsewhere (such as taking longer to pay its own suppliers). You can check out how well a supplier is managing the payment terms with its customers by monitoring the ratio of trade debtors (unpaid invoices at the balance sheet date) with a company’s sales or turnover. A rising ratio could be a sign of a business that is being squeezed.

Cranswick’s trade debtor ratio has been relatively stable but has been nudging up in recent years. This needs to be watched closely but it’s not suggesting that there are currently any big problems.

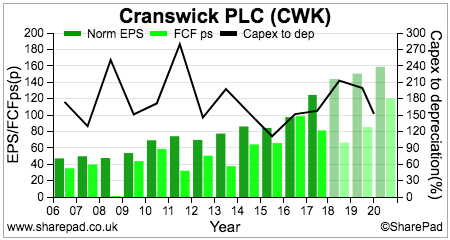

Heavy investment (capex) in new production facilities has meant that Cranswick’s ability to convert its post-tax profits or EPS into free cash flow has been patchier. This might be seen as a cause for concern by some but the fact that its ROCE has been high and stable suggests that the money spent on capex has been money that has been well spent.

Note that the heavy investment in the new poultry factory in Suffolk in 2018 and 2019 is expected to keep capex levels high and lead to weak free cash conversion for the next three years. Investors should not worry about this as long as Cranswick can deliver high returns on this project as it has been able to do on others in the past.

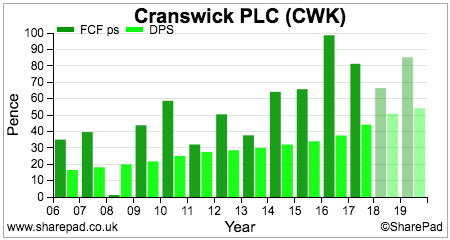

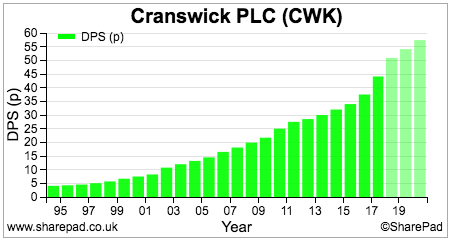

Generally speaking, Cranswick has had plenty of spare cash to pay its dividend. That said, its dividend is not particularly generous and amounts to around one third of annual post tax profits. Shareholders should not complain though as the decision to reinvest profits in the business has paid off handsomely.

Cranswick has one of the most impressive dividend records on the UK stock market. Since its initial listing back in 1995 it has increased its annual dividend in every year and is expected to keep on doing so.

Despite heavy levels of investment, profit and cash flow growth over the years means that Cranswick has very little debt (it has a very small final salary pension fund deficit) and has not asked shareholders for any significant fresh equity since 1995.

Outlook and valuation

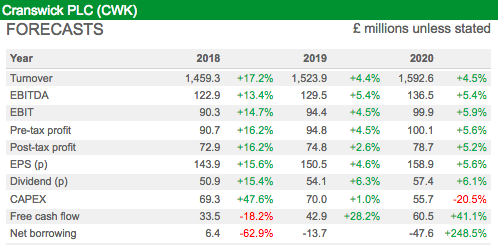

Cranswick’s recent trading performance has been good as evidenced by its trading update in February. The company is well placed to keep on exploiting the growing trend amongst consumers to purchase premium and convenience meat products. It should meet analysts’ profit forecasts for the year to March 2018 when it reports in May quite comfortably in my opinion.

Going forward, current analysts’ forecasts are for more modest rates of growth. This looks to be conservative but quite realistic in my view. Household disposable incomes are under pressure as wage growth struggles to keep pace with inflation. Predicting that consumers are going to significantly increase the amount of premium meat products they buy doesn’t seem to stack up.

That said, Cranswick has been growing faster than its markets recently and its new facilities should boost its competitiveness and allow it to keep on taking market share. The new poultry facility in Suffolk should eventually enable it to take a bigger chunk of the poultry market but this is only likely to be relevant to forecasts for 2020 and beyond.

The one concern that I have with Cranswick is to do with its pricing power. The company is very exposed to the market price of pig meat. During the first half of its 2017/18 financial year this increased by nearly 30%. Cranswick was not able to pass all of this increase on in selling prices and so saw a modest reduction in its profit margins.

In its February trading update it mentioned that the pig meat price had been falling and that this had been reflected in selling prices. This raises the concern in my view that rising pig meat prices can reduce profit margins but lower prices have no benefit to Cranswick as it has to pass them on to its customers.

The company has a good record of maintaining margins with efficiency gains and introducing new premium products, but there is surely a limit to how much incremental margin improvement these can bring. New production facilities will bring benefits as well but the bang for the buck from new investment could also be lower than it was in the past.

Supermarkets – the bulk of Cranswick’s customer base – are trying to rebuild their profit margins which makes it very difficult for Cranswick to increase prices. Analysts are currently forecasting flat profit margins – probably due to the efficiency gains from recent capex kicking in – but this would be my key area of further research if I was looking to buy shares in Cranswick.

The company’s shares have been on a very strong run in recent years but are down nearly 15% since the start of 2018. They currently trade on a one year forecast rolling PE of 19 times at a share price of 2838p.

This is not a cheap valuation but not unreasonable for a business of proven quality. If investors can get some comfort on the medium-term outlook for profit margins then the shares may be worth serious consideration at the current price.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.