The state of the housing market – and the direction of house prices in particular – is a key driver of Britain’s economy. When house prices are going up, people feel wealthier, banks are happy to lend money against property and economic activity tends to increase.

More houses are built, more people move home, more home improvements take place and some people spend some of the equity from their homes. The opposite tends to be true when house prices are falling.

Yet for the best part of the last fifty years the UK housing market has been taken on a boom to bust cycle. There have been booms in the 1970s, late 1980s, mid 2000s and arguably one since 2013. They tend to end badly.

If you are to look at the state of the UK housing market today then it is best described as a mixed bag. The market for existing homes looks to be struggling. Prices are not rising as buyer interest wanes and the number of houses for sale on estate agents’ books is close to all time lows.

The market for new build homes is an entirely different kettle of fish. It looks to be in rude health as evidenced by the stunning profits that are being reported by stock exchange-listed builders.

Housebuilders are in a very fortunate position. The demand for their homes receives significant support from the government’s Help to Buy scheme. This is where buyers of new homes get a five year interest-free loan for up to 20% of a property’s value subject to a maximum buying price of £600,000. The loan increases to 40% in London. In return, buyers have to find 5% of the purchase price.

This means that the government lends up to £120,000 outside London and £240,000 in London towards the cost of a new home. The banks who provide the remaining finance are happy to lend as the loan to value ratios are at worst 75% and could be as low as 55% in London. This means their risk of losing money is quite low if the borrower defaults on their mortgage.

Put simply, it has been a lot easier for buyers to find the money to buy new homes since Help to Buy was introduced in April 2013. It is not really surprising that house prices, builders’ profits and share prices have gone up a lot since then.

But how long can the good times last? Some followers of Redrow were asking this question last week when the Steve Morgan Foundation – a charitable trust founded by Redrow’s chairman – offloaded 25.9 million shares of the builder or around 7% of the company.

Such large share sales always raise suspicions that insiders are calling the top for the share price although it is important to note that Mr Morgan still retains a very large stake in the business.

So should investors be worried or is there still more to go for in Redrow shares?

Let’s take a closer look at the business and see what makes it tick.

House Building 101

House building is a reasonably simple business for people to understand. This is because the profits of a builder are based on five key variables:

- The cost of land.

- The cost of raw materials – bricks, timber, windows, doors etc.

- The cost of labour needed to build houses.

- The selling price of homes.

- The number of homes sold.

The builder has a pretty good idea of the costs of the first three variables. The last two are where the uncertainty exists. The selling price is the key to the eventual profit made on each plot of land. The number of homes sold determines the amount of profit the builder makes each year.

Let’s take a very simple model of a housebuilder to see how this plays out in practice.

Let’s say average selling price per plot (ASP) is currently £350,000. The average land cost per plot is £70,000 and the building, materials and other costs are £210,000 per plot. This allows the builder to make £70,000 profit per plot or a profit margin of 20%.

| Profit per plot | £ 000’s | 10% rise | 10% fall |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASP | 350 | 385 | 315 |

| less: | |||

| Land cost | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Materials & labour | 210 | 218.4 | 218.4 |

| Profit | 70 | 96.6 | 26.6 |

| Margin | 20.00% | 25.10% | 8.40% |

Now look what happens when selling prices change by 10%. The land cost is fixed and other costs are assumed to increase by 4%. The impact on profits and profit margins is very big. This to a large extent is what has typically happened to builders such as Redrow over a house price cycle.

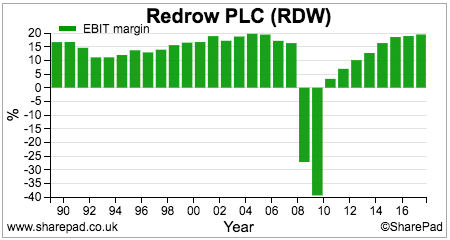

Here is a chart of Redrow’s profit margins going back to 1989. We can see the margins earned in the late 1980s boom, the subsequent fall and the next cycle beginning in the early 2000s with the horrible bust in 2008/09. Margins have been rising since 2010 but have flattened off a little in recent years.

Looking a little closer, we can see that the key driver of profitability and margins over the last 10 years has been selling prices which have increased significantly.

Redrow Private Houses: Selling prices and sales volumes

| Redrow | Turnover(£m) | Volume | Help to Buy | HTB as % | ASP £000’s | % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 1533 | 4305 | 1717 | 39.88% | 356.1 | 8.40% |

| 2016 | 1275.2 | 3882 | 1567 | 40.37% | 328.5 | 10.49% |

| 2015 | 1026 | 3451 | 1374 | 39.81% | 297.3 | 10.40% |

| 2014 | 797.9 | 2963 | 1023 | 34.53% | 269.3 | 18.48% |

| 2013 | 562.3 | 2474 | 82 | 3.31% | 227.3 | 11.37% |

| 2012 | 433.9 | 2126 | 204.1 | 17.23% | ||

| 2011 | 399.9 | 2297 | 174.1 | 12.47% | ||

| 2010 | 342.7 | 2214 | 154.8 | 7.72% | ||

| 2009 | 244.6 | 1702 | 143.7 | -14.41% | ||

| 2008 | 560.1 | 3336 | 167.9 | 4.87% | ||

| 2007 | 757 | 4728 | 160.1 |

The sharp fall in average selling prices (ASPs) in 2009 decimated margins. The subsequent rise in ASPs since then has helped to build them back up.

It is important to realise that the builder does have some control over ASPs. Whilst the general level of house prices is the most important factor, prices can be influenced by geography (they are higher in the south of England than the north for example) and the type of homes built such as the mix between flats and large family homes.

As well as profit margins, the absolute level of Redrow’s profitability is dependent on the number of homes sold. In the context of the current market this begs the question:

Are builders too dependent on Help to Buy?

You can see from the table above that the number of homes sold (volumes) by Redrow collapsed in the 2008/09 recession. They recovered in 2010 and then did not grow much for the next three years.

Help to Buy started in April 2013 and started to make up a significant proportion of Redrow’s private home sales from 2014 onwards and now account for around 40% of all its sales. If you take the view that Help to Buy has pushed up house prices as well since 2013 – by putting money in buyers’ pockets – then you could quite reasonably come to the conclusion that Redrow’s – and other builders’ – profits have had a significant boost from the scheme.

But what happens when the scheme is due to end in 2021?

This is starting to worry housebuilders and they have begun lobbying the government to keep the scheme going. However, they are in a difficult position. Builders are making record profits but the number of homes being built is still some way below what is needed to ease Britain’s housing shortgage. Help to Buy seems to have worked out very well for builders but the country’s housing market still seems broken.

If Help to Buy ends in 2021 will builders be able to sell as many houses and make the same profit margins? There is a risk that they won’t be able to and profits could fall substantially from current levels.

The importance of land

As well as the selling prices for homes, by far the most important factor in a housebuilders’ profitability and returns on capital employed (ROCE) is the cost of its land bank.

Unlike many companies, builders do not have lots of long term fixed assets such as buildings or plant and machinery. The vast proportion of assets on their balance sheets is made up of the land they have bought to build homes on.

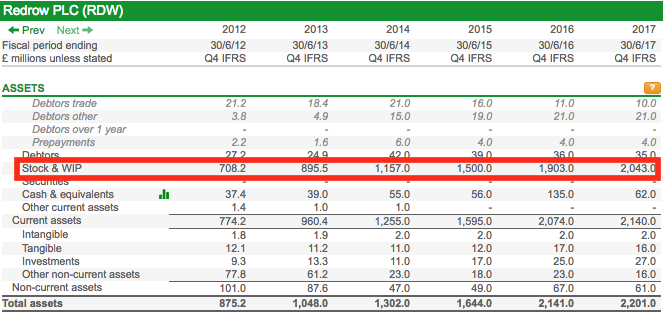

We can see the asset side of Redrow’s balance sheet above. Virtually all of its total asset value is made up of stock and work in progress (WIP). This is the value of land and the value of homes that are being built or remain unsold. At June 2017, Redrow had £1.3bn of land and just over £700m of WIP.

As far as an investor is concerned the value of stock and WIP (also known as inventories) is arguably one of the most important numbers of any house builder. It has a big influence on a company’s profits, net asset value (NAV) and cash flows. It is the key determinant of a company’s ROCE and ultimately how good a business it is.

You will typically see the impact of land in three areas of a company’s accounts:

- As a cost of sales in the income statement when plots of houses are sold.

- As an asset on the balance sheet.

- As an operating cash outflow when land is bought (an increase in stocks or inventory) or an operating cash inflow (a decrease in stocks or inventory) when land is sold.

Land and WIP is accounted for as a current asset. This means that it has to be stated on the balance sheet at the lower of cost or net realisable value (NRV) with its value reviewed every year.

So when the value of land falls it has to be written down with something known as a provison. The provision reduces the value of land on the balance sheet with the company’s profits for the year conncerned reducing by the same amount.

The fall in profits is treated as a one-off or exceptional item and tends to get ignored by investors but it has the potential to impact on underlying profits and ROCE for many years in the future which also tend to be ignored. More on this very shortly.

But how does land rise and fall in value? The answer is based on the changes in value of homes that can be sold on it.

The relationship between house prices and land prices.

This is a bit simplistic but this is how the market value of building land is generally calculated.

What effectively happens is that builders work backwards from the expected selling price of a house, take away the building costs and an acceptable profit margin and what is left over is the price of land. So when houses prices fall the price of land falls by a lot more in percentage terms. This is what happened in 2008-09.

Look at the table below to see what I mean. Say a housebuilder is making a 20% profit margin on each plot sold. Selling prices then fall 10%, but build costs take time to adjust. If the builder want to earn a 20% profit margin on the lower selling price it would pay less for land. In this case, the cost of land drops from 22 to 14 – a 36% drop.

| Profit per Plot (£) | Before | After | % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selling price | 100 | 90 | -10.00% |

| Less: | |||

| Build costs | 55 | 55 | 0.00% |

| Other | 3 | 3 | 0.00% |

| Land | 22 | 14 | -36.40% |

| Profit | 20 | 18 | -10.00% |

| margin | 20% | 20% | 0% |

When house prices fall, the much bigger impact on land prices can wreak havoc with housebuilders’ balance sheets. In 2008-09, most housebuilders posted significant write downs in the value of their land holdings. This destroyed their profits, blew a big hole in the value of shareholders’ equity and limited their ability to pay dividends.

Conversely, when house prices rise, the value of land increases and this tends to get reflected in higher share prices for housebuilding companies. This is what has been happening for the last few years.

The impact of falling land values on a builders’ finances

The first thing to point out is that there is no cash flow impact. There was a cash outflow when the builder bought the land in the first place.

The fall in value reduces the value of land on the balance sheet and profits by the same amount. Retained profits fall which may limit a company’s ability to pay a dividend – as these are paid out of retained profits. Net asset value per share (NAVps) will also fall.

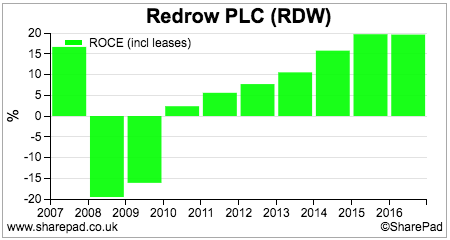

However, in future years the company will be expensing a lower value of land as a cost of sales. If house prices increase, the profit margin on that land will increase. The ROCE will also increase as the profits will be reported on a lower carrying value of land. This is what has played out at Redrow in recent years.

| Redrow Land Provision (£m) | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting balance | 0 | 259.4 | 319.4 | 256.9 | 158.3 | 111.5 | 72 | 48.2 | 28.2 | 19.2 |

| Created | 259.4 | 103.4 | 39.1 | 49.2 | 22.1 | 9.7 | 2.2 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Utilised | 0 | -36.5 | -62.4 | -95.5 | -46.7 | -36.1 | -20.6 | -20 | -9 | -11 |

| Released | 0 | -4.4 | -39.2 | -52.3 | -22.2 | -13.1 | -5.4 | -3 | -3 | -1 |

| Reclassified | -2.5 | |||||||||

| Closing balance | 259.4 | 319.4 | 256.9 | 158.3 | 111.5 | 72 | 48.2 | 28.2 | 19.2 | 8.2 |

| Impact on profits | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Created | -259.4 | -103.4 | -39.1 | -49.2 | -22.1 | -9.7 | -2.2 | -3 | -3 | -1 |

| Released | 0 | 4.4 | 39.2 | 52.3 | 22.2 | 13.1 | 5.4 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Total | -259.4 | -99 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Redrow reduced the value of its land and WIP by £259.4m in 2008 and by a further £103.4m in 2009. The creation of a provision reduces profits.

In the following years the provision is used up – or utilised – when the land it is related to is sold. If a portion of land which has been reduced in value subsequently increases in value then the provision related to it is no longer needed. This is released and boosts profits but has no effect on cash flow.

Provisions can be abused by companies as they are a good way of shifting profits from one year to a future year. By making a big provision in one year it is generally ignored by analysts as a non-trading item but the boost to profits may also be ignored.

The utilisation of a provision has no effect on profits but will affect cash flow if the provision is for a cash expense such as closing a factory. This is not the case with land.

You can measure the impact on profits by calculating the difference each year between provisions created – which reduce profits – and provisions released – which increase them. As you can see, there has been no material impact from this process with Redrow.

What you can see is that the 2008/09 provision was heavily used up between 2009 and 2014 and has now been mainly used up. As of June 2017, there is only £8m remaining.

However, for a few years a significant chunk of Redrow’s sales were accounted for by provisioned plots. Combined with the increase in selling prices, this undoubtedly helped the recovery in its profit margins.

| Year | ASP (£k) | % provisioned plots | profit margin % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 154.8 | 3.2 | |

| 2011 | 174.1 | 74 | 6.9 |

| 2012 | 204.1 | 54 | 10.1 |

| 2013 | 227.3 | 39 | 12.7 |

| 2014 | 269.3 | 20 | 16 |

| 2015 | 297.3 | 12 | 18.5 |

| 2016 | 328.5 | 6 | 18.9 |

| 2017 | 356.1 | 4 | 19.5 |

Despite the continued rise in selling prices, the improvement in profit margins has slowed down as the provisioned plots of land have been used up. Given moderating growth in ASP and cost inflation from labour and materials, perhaps it is reasonable not to expect big improvements in profit margins going forward.

A further look at Redrow’s land bank

Whilst rising selling prices are clearly helpful to a builder’s profits and margins, a lot of thought and effort goes into buying the right parcels of land at the right price. However, it is important for builders to have enough land to build on and hopefully grow profits but having too much land can also be a problem if house prices fall.

| Year | Plots | Potential Plots | Plots + Potential | Completions | Years of Plots | Years of all plots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 26100 | 26400 | 52500 | 5319 | 4.9 | 9.9 |

| 2016 | 26000 | 25634 | 51634 | 4716 | 5.5 | 10.9 |

| 2015 | 18216 | 29580 | 47796 | 4022 | 4.5 | 11.9 |

| 2014 | 16274 | 28245 | 44519 | 3597 | 4.5 | 12.4 |

| 2013 | 14162 | 26024 | 40186 | 2827 | 5 | 14.2 |

| 2012 | 12356 | 22790 | 35146 | 2458 | 5 | 14.3 |

| 2011 | 11190 | 22150 | 33340 | 2626 | 4.3 | 12.7 |

| 2010 | 13170 | 21900 | 35070 | 2587 | 5.1 | 13.6 |

| 2009 | 12570 | 22800 | 35370 | 2113 | 5.9 | 16.7 |

| 2008 | 16450 | 26150 | 42600 | 3925 | 4.2 | 10.9 |

| 2007 | 20700 | 24900 | 45600 | 4728 | 4.4 | 9.6 |

You can work out how many years supply of building plots a builder has by taking the number of plots it has and dividing that number by the current annual rate of completed plot sales. Redrow’s has remained relatively steady between 4.5 and 5.5 years over the last decade.

One area to pay close attention to is the amount of potential plots a builder has. This will include options to buy land and land without planning permission (often referred to as strategic land). It is here that there can be significant hidden or unrealised value for builders if the end market for homes stays healthy.

Strategic land can be bought for a lower price than land with planning permission. If a builder can get it through the planning process then the profit margins and ROCE from selling homes on that land can be very lucrative. Redrow looks to have plenty of potential from its land bank as long as selling prices remain robust.

Keep an eye on WIP as a percentage of sales

The work in progress (WIP) of a builder can be a very large proportion of sales. Stock and WIP gives companies the potential to put some overhead costs on the balance sheet instead of expensing them in the income statement and boosting profits.

| Year | WIP(£m) | Sales(£m) | WIP % of sales |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 723 | 1660 | 43.60% |

| 2016 | 600 | 1382 | 43.40% |

| 2015 | 463 | 1150 | 40.30% |

| 2014 | 360.6 | 864.5 | 41.70% |

| 2013 | 274.8 | 604.8 | 45.40% |

| 2012 | 183 | 478.9 | 38.20% |

| 2011 | 170 | 432.8 | 39.30% |

| 2010 | 211.6 | 396.9 | 53.30% |

| 2009 | 247.9 | 301.8 | 82.10% |

| 2008 | 368 | 650.1 | 56.60% |

| 2007 | 349.1 | 795.7 | 43.90% |

You should keep an eye out for a rising WIP to sales ratio as a warning sign of possible aggressive accounting or overbuilding. You should also compare the ratio with other builders as well. In that context, Redrow’s ratio of 43.6% looks quite high compared with Persimmon (19.6%), Taylor Wimpey (35.8%) and Barratt Developments (32.5%).

There could be a very plausible explanation for this such as the build out phase of sites at the year end but this is something that a diligent investor might want to spend some time trying to understand.

Future outlook and valuation

Redrow released a very impressive set of full year results in early September which contained a very upbeat outlook statement:

“Redrow began the current financial year with a record order book, up 14% year on year to GBP1.1bn. Sales in the first 9 weeks are very encouraging, up 8% on a strong comparator last year.

“Based on the strength of our current performance and the robust demand that we are seeing, we are today updating our medium term guidance. We now expect turnover in 2020 of cGBP2.2bn and pre-tax profit of cGBP430m. We expect the dividend in 2020 to rise to 32p per share.

“Our strategy of continued growth for the business is on track. I am confident this will be another year of significant progress for Redrow.”

To put this in the context of the share price at the time of writing of 555p, the shares trade on a 2018 PE of 7 times or 5.8 times the company’s own 2020 forecast. If these forecasts are met or exceeded then I can see very easily why someone could argue that the shares are cheap.

To counter that, you might argue that the stock market value of its land assets (P/NAV) is close to its historic highs as seen in the chart below.

In a good market with rising selling prices, Redrow’s land should be worth comfortably more than its asset value on the balance sheet. You can also factor in some potential value that could be created from strategic land to bolster the value of the assets.

Yet the uncertainty over the Help to Buy scheme and how long it will last is clearly a concern for investors. Even with a housing shortage, low interest rates and good mortgage availability, it is reasonable to ask whether selling prices can keep rising faster than wages (issues of housing mix and location aside) and therefore how sustainable volumes and profits are.

It is therefore quite difficult to weigh up Redrow and other housebuilder shares at the moment. I will leave you to try and work it out for yourself.

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy or sell shares or other investments. Do your own research before buying or selling any investment or seek professional financial advice.